War History online proudly presents this Guest Piece from Jeremy P. Ämick, who is a military historian and writes on behalf of the Silver Star Families of America.

The Silver Star Families of America has received the personal effects of a local veteran, which help chronicle one of the most devastating tragedies in World War II naval history—the sinking of the USS Indianapolis by a Japanese submarine.

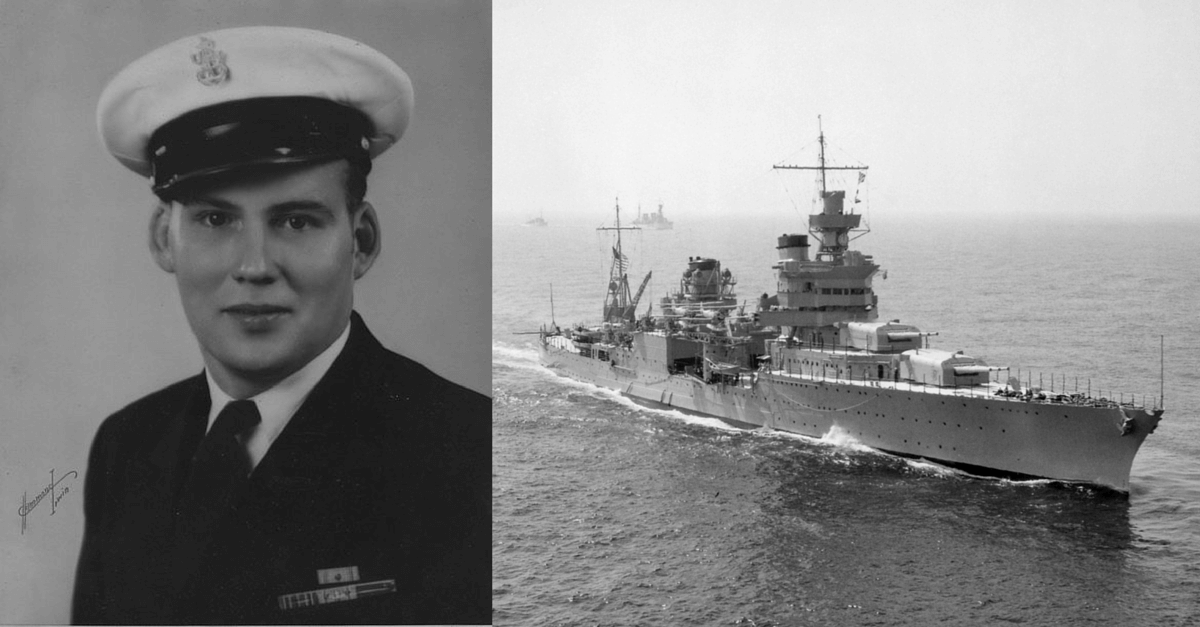

These documents provide a narrow glimpse into the life of former Mid-Missouri resident Wilbur Miller and his service aboard a vessel that has since become a deep-sea grave for scores of sailors.

Born December 12, 1920 near California, Mo., Miller enlisted in the United States Navy on January 16, 1939 following his graduation from California High School.

A listing of duty assignments provided to Miller’s father in Russellville, Mo., by the Navy’s casualty office in late 1945, notes that the young recruit attended boot camp at Great Lakes, Ill., in early 1939, and later received his first assignment aboard the USS Maryland.

The young sailor’s service record continues to show a progression through enlisted ranks, continuing with his transfer to the USS Indianapolis—a heavy cruiser—on April 27, 1940, nearly 18 months prior to the official declaration of war with both Germany and Japan.

Following the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, Miller’s service record demonstrates his participation in a lively list of operations including “the bombardment of Japanese shore installations on Kiska, Aleutian Islands, Alaska” and the “support and occupation of the Tarawa Atoll of the Gilbert Islands from 20 November 1943, to 6 December 1943.”

This tempo of combat operations did not appear to deter the sailor’s desire to serve his nation since the November 30, 1944 edition of The Daily Capital News reported, “(Miller) has been in the Navy six years and says it is his intention to remain in the service until his twenty years is up, after which he will be retired on a pension.”

Bodily injury also had little effect on the trajectory of his naval career even when, as reported in the October 7, 1945 edition of the Sunday News and Tribune, Miller was awarded a Purple Heart for wounds received when a Japanese suicide plane struck the Indianapolis off Okinawa on March 31, 1945.

Through several more engagements in the Pacific theater, Miller and his crewmates performed admirably, but it was an event beginning mid-July 1945 that would permanently etch the name of the USS Indianapolis in the annals of military history.

Leaving San Francisco, the Indianapolis made its way to Tinian Island near Guam, where it off-loaded its top-secret cargo: the components for the atomic bomb that days later would be dropped on Hiroshima, thus heralding the end of the war in the Pacific.

However, the ship—carrying Miller and a crew of nearly 1,200 sailors, Marines and civilians—embarked for the island of Leyte in the Philippines when the unimaginable occurred just after midnight on July 30, 1945.

“ … the USS Indianapolis, was torpedoed by a Japanese submarine, immediately killing nearly 300 men, and sending as many as 900 others into the black, churning embrace of the vast Philippine Sea, some 350 miles from nearest landfall,” wrote Doug Stanton, author of “In Harm’s Way,” a book describing the events surrounding the ships sinking.

The 24-year-old Miller, who was serving as chief machinist mate at the time, is believed to have gone down with the vessel, which sank in less than fifteen minutes following the torpedo attack. Reports of a swift death may have been of little solace to Miller’s grieving family, but what followed for the survivors was nothing short of a nightmare.

Though an estimated 900 of the crew made it into the ocean waters once the ship submerged, nearly 600 of them died while spending almost five days afloat, suffering from starvation, dehydration and fatigue, while others were torn apart during frequent shark attacks. When the surviving crewmembers were rescued, only 317 remained.

Miller’s father, Frederick, was informed of his son’s death in early October 1945, leaving him with only his daughter, Virginia (his wife passed away 11 years previous).

During a memorial service on November 18, 1945 at St. Paul’s Lutheran Church in California, the choir sang for their departed son “The Navy Hymn” by John B. Dykes, the first verse of which provides a fitting closure to the life of a local man who will remain forever at sea.

“Eternal Father, strong to save, Whose arm doth bind the restless wave, Who bidd’st the mighty ocean deep, Its own appointed limits keep; O hear us when we cry to Thee, For those who peril on the sea!”