Imagine the following scenario: you’re with the Allies during WWII. Fortunately, your side eventually won. Unfortunately, you’ve ended up in a Nazi POW camp before that happened. You obviously have to escape – but how? With the help of a Monopoly game, of course.

It all began with Christopher “Clutty” Clayton Hutton. During WWI, Hutton served the Royal Flying Corps as a pilot. When it ended, he did a stint as a journalist and as a publicist for Hollywood.

Then WWII came, Hutton again enlisted, but the British government wasn’t interested in his flight record. They were more interested in a challenge he gave Harry Houdini – the famous escape artist.

Since his family owned a timber mill, Hutton issued a challenge to Houdini in 1915 – escape from a box made by the company. Houdini accepted on condition that he got to meet the carpenter who was going to make it. Hutton agreed, only to later find out that Houdini had bribed the man into designing a box that would let him escape.

Thus began Hutton’s fascination with the world of illusion, trickery, and escape artists. It also explained why the Military Intelligence Section 9 (MI9) wanted him, since it was responsible for the escape of Allied POWs, as well as working with resistance movements in enemy territory.

Hutton came up with fantastic inventions to give servicemen a fighting chance. This included compasses so tiny, they could fit in buttons, heels that hid knives, compasses, and maps, boots that could turn into civilian shoes, and telescopes disguised as cigarette holders. Many were discovered, so Hutton had to constantly invent something new.

In a nod to the Geneva Conventions, Germany allowed POWs to receive letters and packages from their families and various charities. The Red Cross was therefore allowed to get into POW camps, but British Intelligence refused to compromise them, forcing Hutton to turn to Britain’s latest fad – Monopoly.

The now-classic board game had arrived from America in 1935, and John Waddington Ltd. got exclusive printing and packaging rights. They also had the right to “Britify” the game by replacing American streets with those in London.

The Waddingtons had other businesses, however. One of these was silk printing – a technology they perfected by mixing ink with pectin to prevent the ink from running. Their company was, therefore, responsible for making the playbills given to the Royal Family during performances.

Hutton understood the value of silk maps over paper ones since the former survived moisture without warping or dissolving. They could also be scrunched up into smaller pieces and still be laid out flat without creasing. Best of all, they were a lot sturdier and could be opened and closed quietly, unlike paper ones.

Waddington had already been producing such maps for MI9 which were sewn into British uniforms – all of which were discovered by the Germans. So Hutton came up with a better plan.

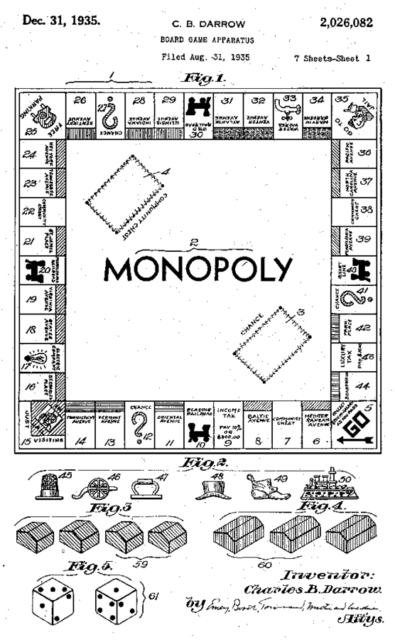

Hide the maps and other escape equipment in Monopoly games. Victor Watson, the company’s chairman, set aside a separate room for the task and assigned a few trusted employees to the job.

Monopoly boards used to be 1/8th of an inch thick, so workers created pre-cast boards with tiny compartments that held silk maps, knives, chords, and compasses. The boards were then glued together, but they also had to make sure the final result weighed about the same as the other games.

So now MI9 had to figure out how to get them to their POWs. That wasn’t a problem because Germany allowed prisoners to receive games, believing it kept their minds off escape and made them more manageable.

POW camps also had escape committees that decided which of them had a good chance of making it. These used escapees to get information out to the Allies, where possible, since a number had been trained in the use of secret codes.

To avoid compromising legitimate charities, MI9 invented fake ones based in addresses that had been bombed out. The first 13 Monopoly games sent to POW camps in German-occupied territory were legitimate, but they arrived with receipt cards.

These listed each item that came in care packages which prisoners had to tick off and send back. After the first month, nothing happened. By the end of the second month, still nothing, so British intelligence wrote the whole business off.

At the start of the third month, however, the cards began trickling in – success! So now they had to let the prisoners know what they were getting. Using secret codes embedded in letters from “mum and dad,” MI9 was able to establish a communications relay with POW camps throughout Europe.

That established, they began sending out the special Monopoly boards. Depending on the information they received, they were able to tailor the games, accordingly. Sometimes, real money was hidden among the fake ones so escapees could buy whatever they needed. At other times, the token pieces were made of real gold for the same purposes.

Special boards were marked with a red dot on the Free Parking space. Those which had maps of Italy had a period after Marylebone Station. If it came after Mayfair, then the map was for Norway, Sweden, and Germany. Northern France had a period after Free Parking.

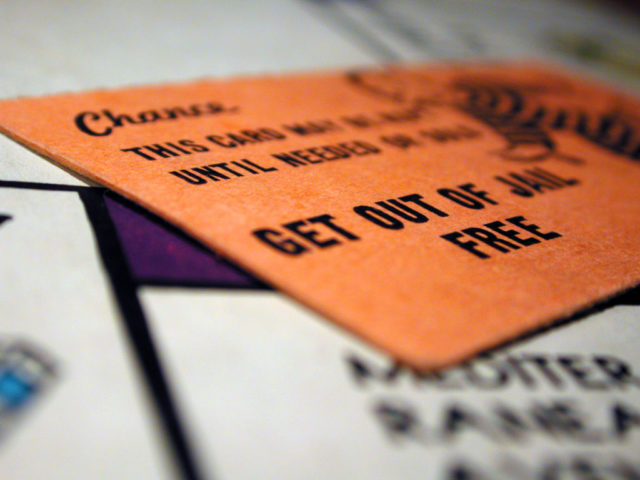

In the winter of 1943, these Monopoly games saved thousands of lives. US Lieutenant David Bowling was a prisoner at Stalag Luft III outside Berlin, when he was ordered to escape.

The camp was run by the Luftwaffe, but with the tide turning against Germany, the SS had a plan. They wanted to take over in order to send the prison guards to the war front. So who would guard the prisoners? No one. The SS was going to kill them all.

Since Bowling spoke German, the committee gave him everything he needed. Against all the odds, he made it to neutral Switzerland and relayed the message.

The Allies used their Swiss contacts to inform Heinrich Himmler (head of the SS), that if he carried through with his plan, he’d be held personally responsible. Himmler got the message, chickened out, and spared the POWs.

Of the 35,000 Allied prisoners who successfully escaped, it’s believed that perhaps 10,000 did so using Monopoly – an excellent use of its “Get Out of Jail Free” option. Best of all, the Germans never discovered the real nature of the games.