During WWII, thousands of combatants were taken prisoner by their opponents. To help Allied troops who had been captured and to get the best possible advantage from any information they might have, the British established MI9, a secret organization dedicated to working with Allied prisoners of war (POWs).

The Creation of MI9

During WWI, several British POWs escaped from German camps. Their exploits were the subject of popular books in the interwar years, glamorizing escape and evasion.

Late in that same war, MI1, a British intelligence body, became interested in the information obtained from German POWs and from British servicemen who had escaped captivity.

With the outbreak of WWII, military intelligence was given a sudden jolt into action. An interest in POWs as a source of information was revived, together with helping Allied troops escape from Axis camps. Major J. C. F. Holland of Military Intelligence Research (MIR) wrote a paper proposing a new department to handle it which was accepted by the Joint Intelligence Committee (JIC).

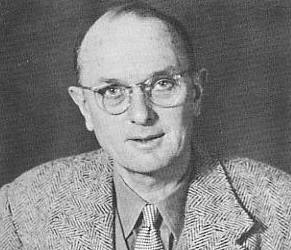

Again following Holland’s advice, JIC put Major Norman Richard Crockatt in charge of the newly formed MI9. The 45-year-old officer was a veteran of WWI who had been awarded the Distinguished Service Order and the Military Cross. Good at coordinating and quick-witted, he was not a man to be restricted by red tape.

The charter for the secret organization, issued on December 23, 1939, gave it five tasks:

- Help British POWs in their escapes, so they could return to combat and use up enemy resources in guarding them.

- Help the escapees to avoid capture while in enemy territory.

- Collect and distribute information.

- Help deny the enemy information.

- Maintain the morale of British POWS in enemy camps.

Escape

Helping with escapes was the most significant part of MI9’s activities.

The groundwork for escapes was laid before men went into action. Training was given to servicemen in how to deal with imprisonment and the methods that could be used to get away. RAF fighter and bomber personnel, who for a long time were the most likely to be captured, were trained and equipped in advance for escapes.

The equipment, much of it created by Christopher Clayton Hutton, was often ingenious. All sorts of metal objects were magnetized to provide improvised compasses. Wire saws were hidden in laces. Maps were hidden in handkerchiefs that only revealed their markings when washed. Other items were hidden everywhere from buttons to boot heels.

The boots worn by airmen were adaptable. The lining and other parts could be removed, to become a waistcoat and the boots civilian shoes to use as a disguise. As well as the equipment they arrived with; prisoners were often sent escape tools. Packages were secretly marked so they would know which ones to stop the guards searching.

One line that was never crossed was the sanctity of Red Cross parcels. The British respected the importance of Red Cross neutrality and never tried to hide anything in their care packages.

Evasion

Evasion was as important as an escape. In the days following the fall of France and the Dunkirk evacuation, scattered British service personnel made their way to the coast or neutral countries. Later, escapees had to find ways to reach those safe havens despite the attention of the SS, German Army, Gestapo, and authorities of occupied nations.

Again, training was essential. Based on the experience of escapees, including those who evaded capture during the fall of France, briefings were given on how to blend in. A lot of it was in the details – how they should dress and their body language. To slouch instead of marching. Carry a bag as the locals did. Wear a beret to blend in when in rural France.

The instructions included how to behave once an escapee reached the next step – the escape lines. They were the covert organizations that provided safe routes out. British agents were parachuted into enemy occupied territory where they coordinated with local resistance members to set up the routes. Many lost their lives when the Germans uncovered what they were doing. Despite the risks, they helped many POWs escape to safety via neutral Spain or Switzerland.

Information

Information gathering was equally vital to MI9’s work. It was partly a way of improving escape and evasion. The experience of those who had succeeded was invaluable for future captives.

It was also about advising British intelligence about Axis activities. POWs knew details about their capture and what they had seen both inside and outside their camps. Intelligence was gained on everything from enemy fighter tactics to troop dispositions to the state of German morale. On one occasion, an imprisoned radar expert gleaned vital information on German technology which helped keep Britain ahead in the air war.

Some of the information came from escapees, but much of it came from inside the camps. By the end of the war, every camp for Allied officers contained a hidden radio set, either built by captives or smuggled in by MI9. They enabled MI9 to send messages useful for escapes and to extract intelligence. Coded letters also played an important part.

Morale

Maintaining POW morale became a subsidiary part of all the activities. Supply packages, whether containing covert materials or not, were a good way to keep men’s spirits up. A sense of purpose was equally important. The possibility of escape gave prisoners hope. Gathering intelligence gave them a way to contribute to the war effort.

Simply by existing, MI9 helped in maintaining morale for British POWs and the Allied men imprisoned with them.

Source:

Ian Dear (1997), Escape and Evasion: POW Breakouts in World War Two