Germany was not the first country to go on the offensive on the western front of World War Two. That first attack came from France, which launched a brief and ineffective invasion of Germany in September 1939. This attack, intended to help the far-away Poles, became an embarrassing defeat and a harbinger of what would follow when Germany invaded France.

The Aim of Operation Saar

Following the First World War, both France and Poland had reasons to fear future German military aggression. Since Prussia united the fractured German states under its leadership in the 1860s, German leaders had used military action against their neighbours to east and west both as routes to territorial aggrandisement and a way to keep Germany united. Germany was a nation with a reputation for belligerence, whose troops had marched through both countries in the First World War.

To counter this German belligerence, the French and the Polish governments agreed to a military treaty in 1921, binding them to support each other in any war against Germany. It was on the back of this treaty that, two days after the German invasion of Poland on 1 September 1939, France declared war on Germany.

At the time, the declaration of war was a largely symbolic act. Like Britain, which had declared war on the same day, France was too far from Poland to offer real aid in driving back the invaders.

But one possibility offered itself. An invasion of western Germany by French troops might draw soldiers away from the attack on Poland. Failing that, it would at least give France a head start in the war that must inevitably come her way.

The Saar Offensive

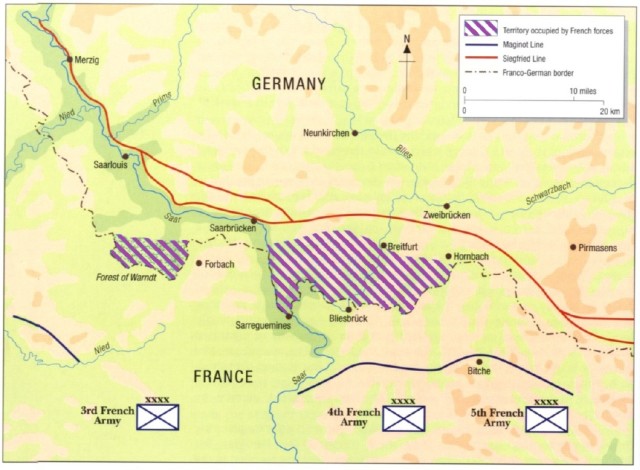

What followed was Operation Saar, an invasion of the German region of Saarland. Unfortunately for the French, the restrictions that bound them to this plan would also ensure its failure.

The French did not want to violate the neutrality of Belgium by taking armed forces across its territory. As a result, they could only attack Germany along a limited front. This front had been defined 125 years earlier, during the peace process following the Napoleonic wars, when the rest of Europe was concerned with containing French aggression. It gave the Germans the advantage of the defensive high ground.

Still, the French had made a promise to Poland, and they lived up to it. On 7 September they invaded Saarland with a limited force, which was due to be followed by a full-scale invasion a few weeks later. Forty divisions were sent in, with 4,700 artillery and 2,400 tanks. Facing them were 22 divisions and less than 100 artillery pieces of the German 1st Army.

The Advance Stalls

The French advanced five miles into Germany, taking a few towns and villages. The Germans had evacuated this territory, pulling back to the prepared defences of the Siegfried Line. They left behind minefields and booby-trapped houses to slow down and damage the advancing French. The French came unprepared, lacking mine detectors.

Part of the problem was the French mobilisation plan. They had been expecting to face an attack by Germany and were prepared for this. But despite their commitment to the Poles, they lacked an adequate plan for taking the war to Germany.

What plans the French did have were outdated, relying on the strategies of the First World War, the slow and bloody advance of trench warfare and protracted bombardments. But as the Germans were showing in the east, this was a new age of warfare. Victory now relied on fast advances and swiftly flowing forces, using hard-hitting, swift-moving tanks and transport vehicles that had not existed during the First World War.

Even for the plans they had in mind, the French mobilisation system was outdated. They lacked the ability and the will to swiftly mobilise a large army and put it to effective use. The first steps towards mobilisation had only started on 26 August, and full mobilisation on 1 September, following the German invasion of Poland.

As the French army dragged itself into action, its advancing formations came within artillery range of the Siegfried Line. Here they discovered the effectiveness of the German defences and the ineffectiveness of the guns they had brought. To fire on the Siegfried Line they had to bring their artillery within range the answering German firepower. The French had far more guns, and their bombardment fell both accurately and rapidly on the German positions, but the guns could not penetrate those defences. Some fired 155mm shells, not heavy enough to make a real impression on the concrete bunkers. Those firing 220mm and 280mm shells might have done better, but their ammunition did not have delayed fuses, and so exploded on impact rather than penetrating the outer casements first. Explosives were hurled against the German line to little effect.

Withdrawal

On 12 September, the British and French met. They already believed that Poland was a lost cause, and so decided to halt all operations while a long-term plan was developed. Advancing troops stopped short of assaulting the Siegfried Line. The Poles, who had not been consulted on the decision, were told that the full assault on the western front was delayed until 20 September.

On 17 September, the invasion of Poland by Russian forces ended any small hope that remained for the Poles. French forces withdrew from Saarland, leaving only a small holding force. The full assault was cancelled.

With Poland defeated, German troops were sent west, and on 16 October they launched a counter-offensive in Saarland. As planned, the French troops withdrew, leaving the Germans to retake the captured territory. The French pulled back to defensive positions along the ill-fated Maginot Line.

Little blood had been split over Saarland to distract the Germans. Even less effort had been expended. The French had shown that they were not prepared for an offensive war, and settled into a defensive position that they would also soon lose.