Julius Caesar’s Gallic Wars had been raging for over five years when his legions faced their greatest test at the double siege of Alesia, a ferocious and monumental battle that was so great in numbers, logistics, and daring that it still has few rivals in European warfare to this day.

Caesar had thought Celtic Gaul, the area approximately corresponding to modern day France, Belgium, and Rhineland Germany, conquered after his initial victories during the campaigning seasons between 58 and 54 B.C. In late 54, however, as his legions were spread around the country in winter quarters and Caesar himself cut off in Italy by Alpine snows, the tribes of Gaul united and rose against the Roman occupiers. The 14th legion was entirely destroyed after being betrayed by tribes purporting to be allies, and it looked, momentarily, like all of Caesar’s work would be undone.

As it was, he managed through a Herculean effort to move himself and reinforcements across the snow covered mountains into the main area of operations, and after splitting his forces, he went on the trail of the man elected by the usually fractious Gallic tribes to be their sole leader: Vercingetorix.

A very capable political and military thinker, Vercingetorix managed to elude Caesar through canny manoeuvring early in the campaign, but he understood that an open engagement against the battle hardened legions of Caesar’s host would be tantamount to suicide. With that in mind, he moved with a force of upwards 80,000 men to the hill fort of Alesia in central Gaul, there to await further reserves from the mustering tribes.

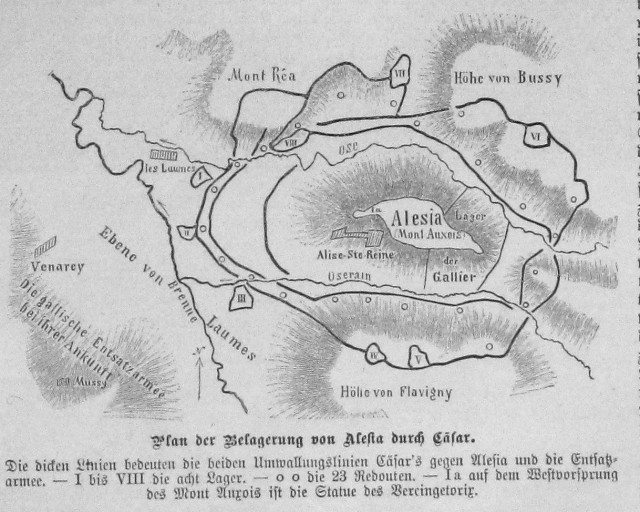

Pursuing him furiously, Caesar settled down to a siege and completely encircled the fort with a ring of earthworks. These were elaborate ditches and ramparts, including guard towers and heavy weaponry like catapults and ballista – effectively giant crossbows. After three weeks, the earthworks stretched for over ten miles all around the fort’s perimeter, a huge trench before the fort’s walls, then a line of other ditches four hundred yards beyond that filled with water from a nearby river, before another trench and then Roman ramparts and timber breastworks. The details and numbers involved in the campaign can be recounted in such detail because Caesar kept a diary record himself and published them in book form as “De Bello Gallica (The Gallic Wars)”.

It was his strategy that such an enormous number of warriors inside the cramped town, along with the ordinary inhabitants, would be forced to capitulate in a very short time. To ensure that it was not his side that fell to hunger, he had each man under his command forage enough grain and fodder for thirty days. Vercingetorix foresaw this eventuality also, and he moved to prolong his supplies as far as possible. The non-combatants of Alesia, primarily women, children, the sick, and the old, were turned out of the town, where it was assumed the Romans would allow them to pass out of the war zone. Against the ordinary run of warfare, Caesar ordered that they were not to be allowed though the Roman lines, so they were left outside the walls of the town to hunger and the elements. The Gauls would not allow them back inside the town and in desperation the starving people offered themselves as slaves to the Romans, who nevertheless remained unmoved in the face of their suffering.

Vercingetorix had come close to breaking through the lines with sorties and night time raids, but in very late September/early October a massive relief army of Gauls appeared and surrounded the Roman lines from the rear. The besiegers had now in turn become the besieged. Caesar himself put the size of this Gallic army at above a quarter of a million men, as opposed by his own sixty thousand legionaries and auxiliaries, not to mention Vercingetorix’s sizable though weakened force inside the fort itself. Working against all odds, Caesar’s hungry and exhausted legionaries constructed another ring of earthworks ten miles long, this one facing in the opposite direction and designed for their defence.

Their commander ordered them to dig in and face the coming storm, and Caesar’s status as one of the world’s great generals was proven in the manner that he conducted himself during those fraught days. Prior to the main Gallic attack, he rode around the lines, talking to the men and rejuvenating their morale. The next day, October 2nd 52 B.C., the Gallic onslaught began.

The legions were hit by tens of thousands of screaming warriors in an area of the lines where the natural topography made strengthening earthworks difficult, the attack led by a man named Vercassivevellaunus, the cousin of Vercingetorix. At the same time, the Gallic forces still active in the fort of Alesia streamed down the hillside at the sound of a signal trumpet and attacked the Romans from the other side. Fighting on two fronts, it looked like the Roman siege was over. Just when all seemed lost, a familiar figure rode into the breach and led the counter attack. Caesar, calling on his centurions by name and wearing a conspicuous cloak, rallied his forces, and seeing their commander in danger, the Romans redoubled their efforts and threw off the attackers. The Romans attacked the enemy from distance with slingshots firing heavy lead bullets, and sharpened javelins, known as pila. When they had the advantage of height, they flung heavy rocks and boulders at the attackers, anything that would break the charge and disorder their lines. Vercingetorix’s men used grappling hooks to try and pull down the Roman towers and breastworks, succeeding in many cases to destroy the Romans’ engineering feats. Finally as the light began to fade, Caesar brought his last cavalry reserve forward, and the sight of these horsemen threw the Gauls in retreat. The relief army was scattered.

When the sun rose the following day, anywhere between 50,000 and 100,000 Gauls lay dead on the battlefield, eight times the number of Romans killed. Vercingetorix surrendered unconditionally to Caesar, and his army’s 40,000 survivors were taken prisoner. The power of the Gallic tribes was broken and the area would remain in Roman hands for half a millennium. Their leader was held in captivity for six years before being put to death before the Roman mob. Caesar, on the other hand, was granted twenty days of thanksgiving by the senate and people of Rome, and his ascendency to ultimate power continued.

Though today his conquest of Gaul would count as a crime against humanity, history has judged Alesia not only to be a high water mark of Julius Caesar’s career as a military commander, comparable to Napoleon’s victory at Austerlitz or the Allied D Day landings, but also as one of the greatest victories of the Roman Army itself, a prize not lacking in contenders given that body’s incomparable continuity and longevity.

Image 1, source: Wikipedia

Image 2, source: Wikimedia Commons

Image 3, source: Wikimedia Commons

Image 4, source: Wikimedia Commons