Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, anti-Japanese sentiment spread across North America. The governments of the United States, Canada and even Mexico decided it best to segregate their Japanese populations from the general public, leading to the creation of controversial internment camps.

Government orders against those of Japanese heritage

Following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, there were calls for the government to enact a mass incarceration of everyone of Japanese heritage. Just hours after the attack, the FBI conducted raids on homes owned by the Japanese-American community. Thousands of items considered contraband were seized, and 1,291 individuals were arrested without cause.

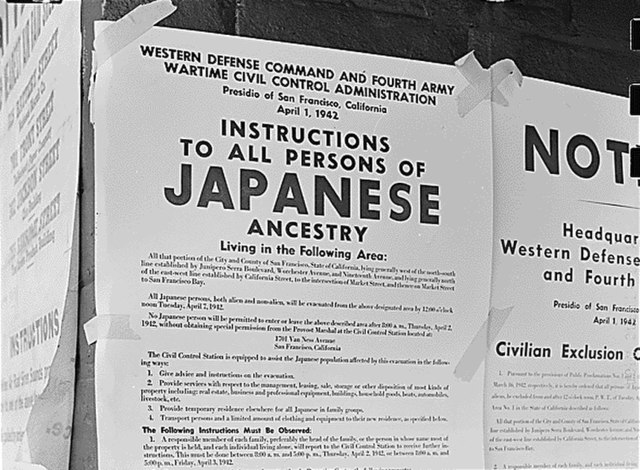

Following a petition from Lieutenant General John L. DeWitt, leader of the Western Defense Command, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942. Created with the intention of preventing espionage on American soil, it ultimately led to the removal of Japanese-Americans to designated internment camps.

Similar actions were occurring in Canada, which were further fueled by the Japanese attack in Hong Kong, which led to the imprisonment and death of the 2,000 Canadian soldiers stationed there. Within days of Pearl Harbor, Canadian Pacific Railways fired its Japanese workers, a move followed by other Canadian companies. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police also arrested suspected Japanese operatives along the Pacific coast, and the Canadian Navy impounded 1,200 Japanese-owned fishing boats.

Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King issued the Order-in-Council P.C. 1486 in early 1942, which called for the removal and detaining of “any and all persons” from any “protective area” in the country. This included a 100-mile strip of land along the Pacific coast, which had been created on January 14, 1942. Japanese-Canadian males between the ages of 18 and 45 were sent to road camps in interior British Columbia, and their homes and businesses sold by the Canadian government.

While the detention of Japanese individuals widely occurred in the US and Canada, it also occurred in Mexico, Brazil, Peru, Argentina and Chile, with detainees sent to the US for incarceration.

Japanese-Americans are sent to internment camps

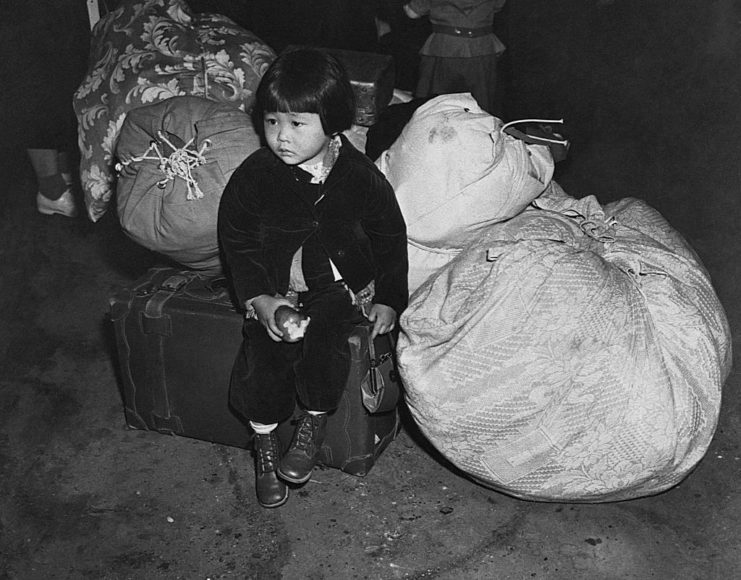

For the duration of World War II, it was government policy that those of Japanese descent – including US citizens – be imprisoned in isolated internment camps. This began on March 24, 1942, affecting the lives of 120,000 people until the end of the war in 1945.

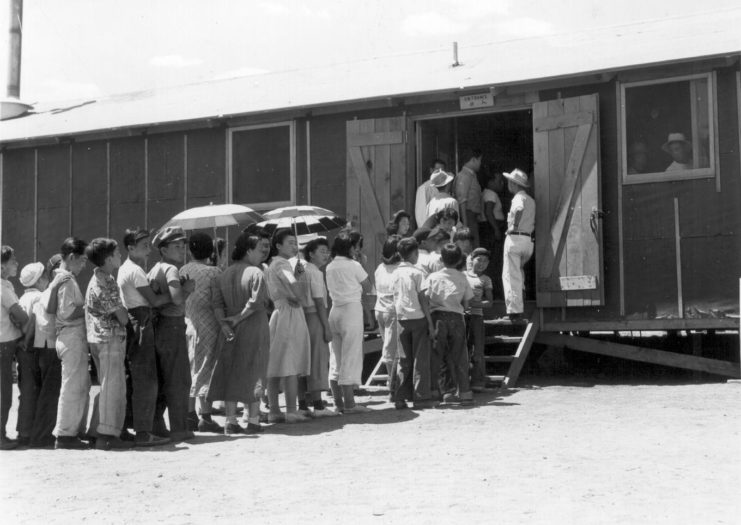

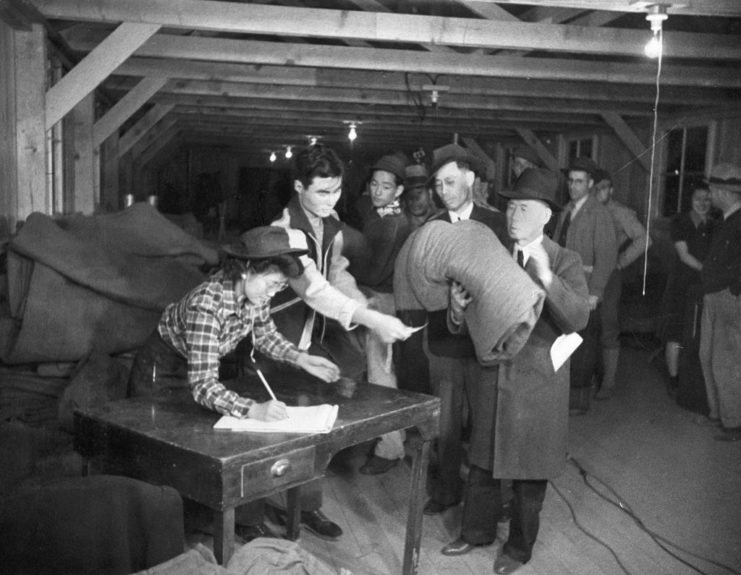

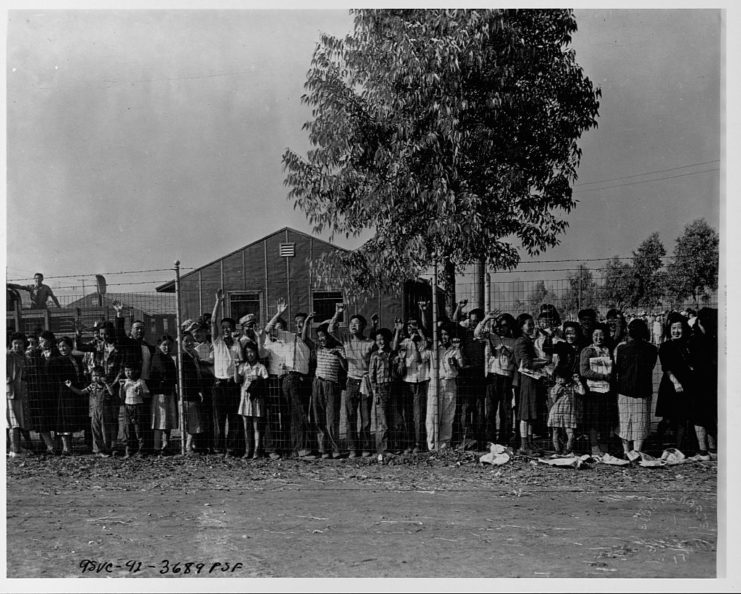

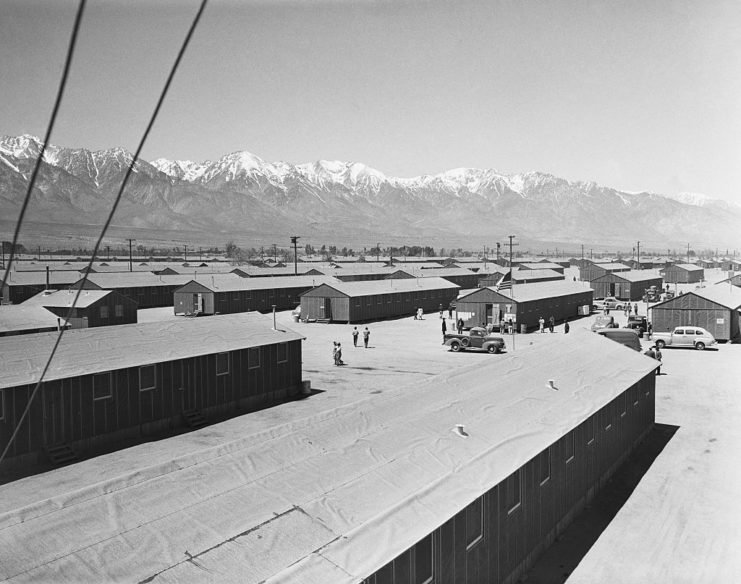

After being given six days to collect their belongings, Japanese-Americans were told to report to “Assembly Centers” – reconfigured racetracks and fairgrounds – where they endured food shortages, substandard sanitation and lived in quarters originally intended for animals. Once processed, they were sent to one of 10 prison camps, called “Relocation Centers.”

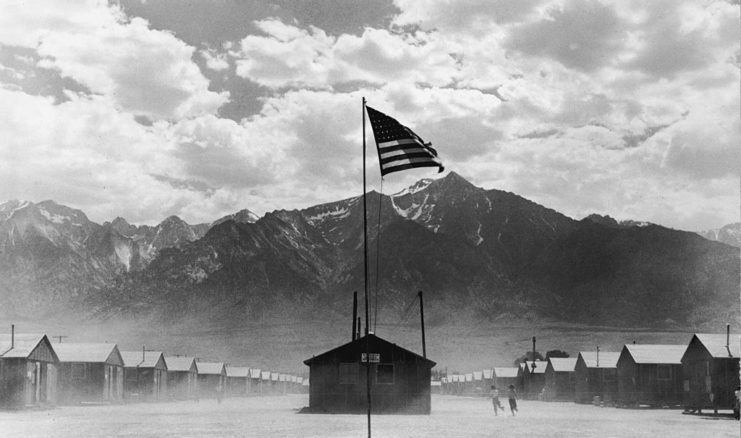

Relocation Centers were located along the West Coast, largely in Arizona and California, with dissidents being sent to the Tule Lake Relocation Center in California. Two of the camps were located on Native American reserves, with protests from tribal councils overruled by the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

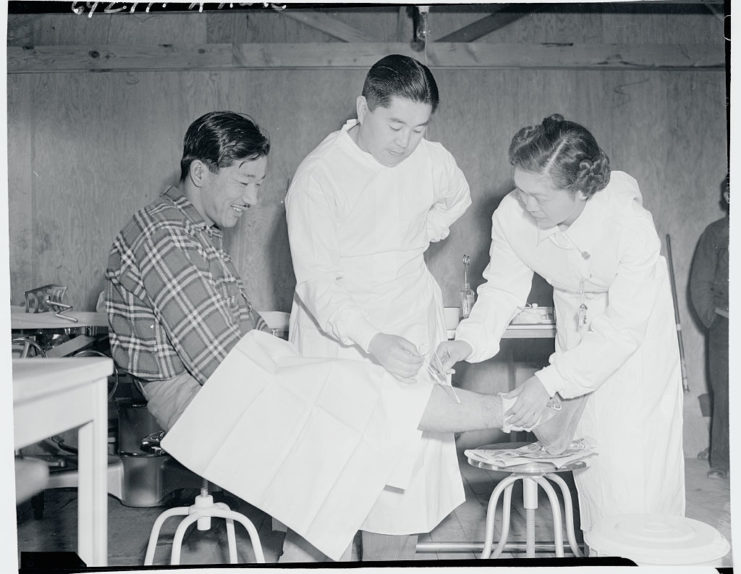

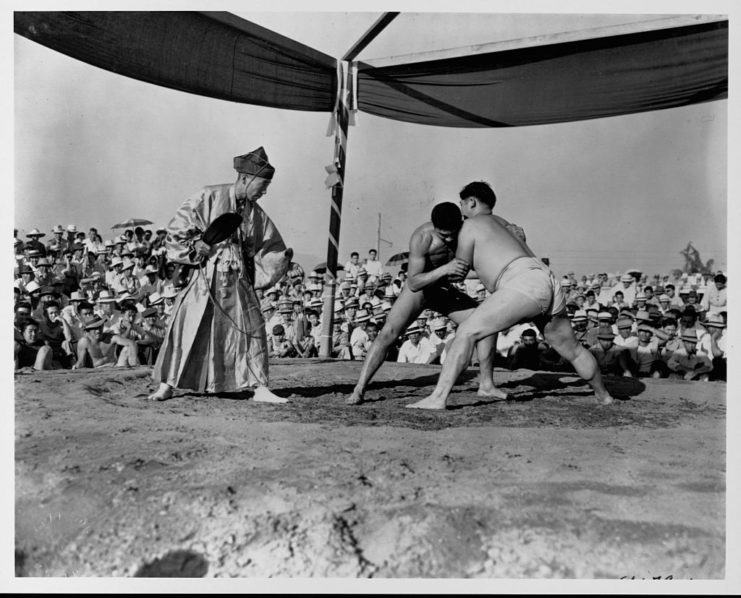

Each was designed like a town, with schools, post offices, mess areas and work facilities. Despite this, living conditions were substandard. The camps were surrounded by barbed wire and armed guard towers, and families were housed together in army-style barracks with little-to-no privacy. While allowed to work, jobs were low-paying and largely labor intensive. There was also an issue with occasional violence.

Japanese-Canadians targeted in the Interior

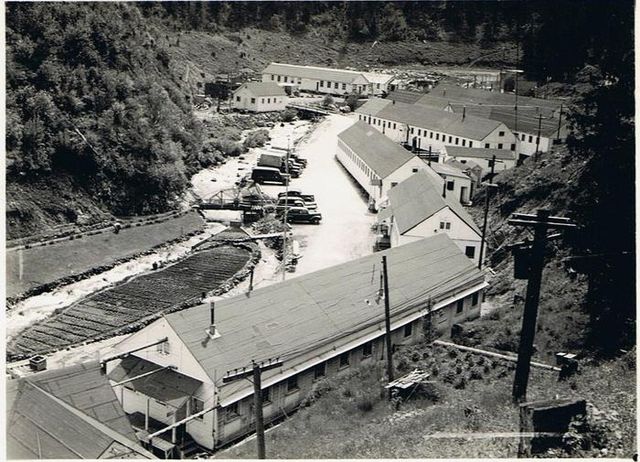

While the number of Japanese-Canadians affected by internment was less than that seen in America – 21,000 versus 120,000 – the total amounted to around 90 percent of the overall population. It began on March 16, 1942, when the first group of detainees were taken from areas 160 KM inland and brought to Vancouver‘s Hastings Park. It’s estimated 8,000 people were processed.

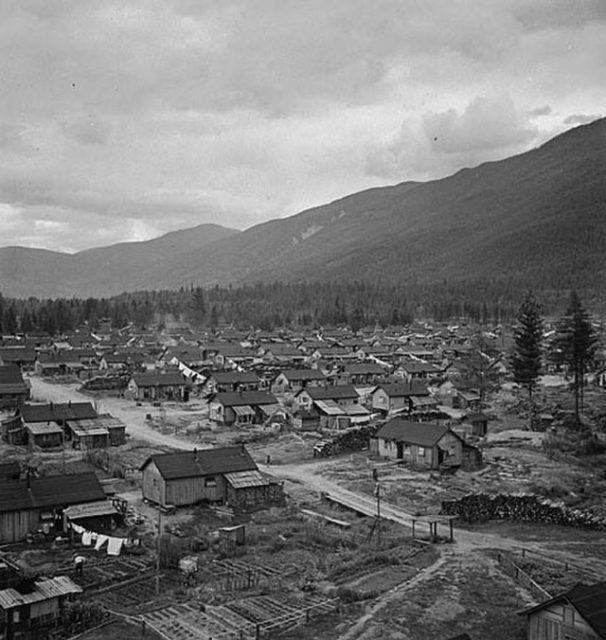

Trains then began to carry Japanese-Canadians to ghost towns-turned-internment camps in New Denver, Kaslo, Slocan, Sandon and Greenwood. Those who didn’t want to be taken to the camps were given the option of working on sugar beet farms in Manitoba and Alberta, although they were treated to poor living conditions, substandard pay and racism from their employers.

Unlike their American counterparts, the internment camps in Canada were not surrounded by barbed wire. However, it could be argued their conditions were far worse. There was a serious issue with overcrowding, and many (if not all) of the camps had no running water or electricity. Those who resisted their detainment were sent to prisoner of war camps in Petawawa, Ontario or to Camp 101 on the northern shore of Lake Superior.

A racist legacy

In the US, the internment of Japanese-Americans is considered one of the worst violations of American civil rights in the 20th century. It wasn’t until 1976 that President Gerald Ford repealed Executive Order 9066, and it took another 12 years for Congress to issue an apology and pass a law, allowing those imprisoned at the camps a reparation of $20,000 each.

Following the conclusion of WWII, Prime Minister Mackenzie King continued to attack Japanese-Canadians. Instead of allowing them to return to their old residences, he gave them two options: move to Japan, or leave British Columbia for areas to the east of the Rocky Mountains. It’s estimated some 40,000 individuals opted to leave Canada.

Mackenzie King never showed any remorse for his actions toward Canada’s Japanese residents, a sentiment that continued with Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau, who in 1984 refused to apologize for the government’s treatment of those of Japanese descent.

It wasn’t until 1988 that those who were victims of the country’s internment camps received an apology from the government. Prime Minister Brian Mulroney also repealed the War Measures Act and gave each former detainee $21,000 in redress payments.