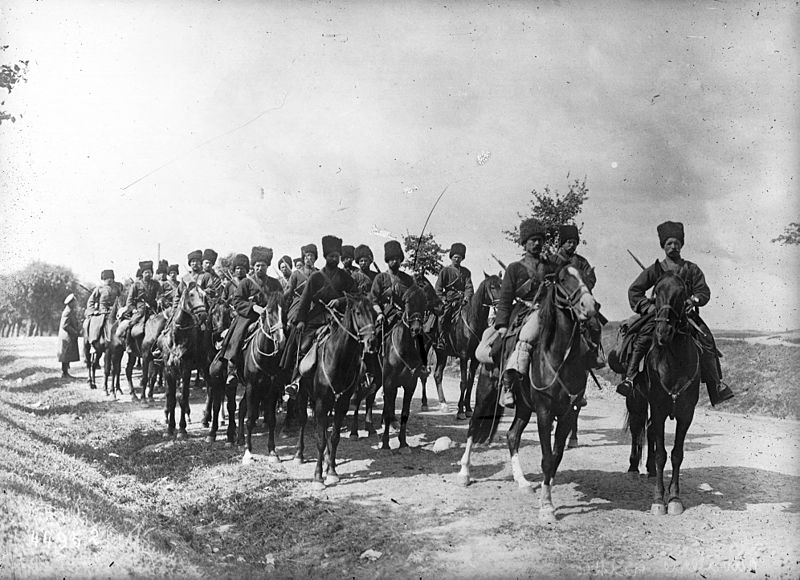

The existence of the Cossacks immediately became news even without confirmation as to whether there is truth to the stories of their sightings.

News spread like wildfire of the millions of Cossacks of the Russian Army being destined to Britain a few weeks after the outbreak of the First World War. The fighters were said to be sent to various destinations in Europe to fight in the Western Front. The fighting then was intensifying and the trenches were yet to be the main site of the long conflict.

Even Germany heard word of their existence and moved to make about strategic changes in their war efforts. The Allies immediately grabbed the opportunity to stop them from achieving victory.

However, there was but little truth in the information that went around. In fact, recent reports reveal that the Cossacks, rumored to number in millions, were non-existent.

The existence of the Russian Cossacks, also called the “Russian rumor”, is one of the myths and legends which abound during World War I. Recently, David Clarke of the Sheffield Hallam University who specializes in analysing such “event” made a move to investigate the myth.

The research also includes the rumored Angel of Mons – an apparition which was believed to have assisted the British soldiers. Another phenomenon under investigation is the spying missions conducted by the “phantom” Zeppelins. Other myths include “corpse factories” where the Germans were rumored to process human remains. All these are in line with the series of lectures conducted to mark the centenary of the World War I.

Dr. Clarke traced the origins of the “Russian rumour” including the reports that were abound during the time. He showed how the British spies brilliantly used the rumor to trick the Germans.

In the last week of August of 1914, rumours of the massive force of Cossacks started to circulate. After, the rumours spread swiftly in the media. At first, it was the local newspapers. Then, it filled the columns of national and international newspapers.

Witnesses were said to have seen trains headed southbound travelling through the country with closed blinds. But, the passengers of carriages were said to take occasional glimpse to the outside revealing the faces of “fierce-looking bearded fellows in fur hats”. The train drivers also claimed that the said men spoke a foreign language.

A news article also revealed reports that an “immense force of Russian soldiers – little short of a million it is said – have passed, or are still passing, through England on their way to France”. It also hinted of the whereabouts of the men. The news said that they were from Archangel, in northern Russia, and arrived at Leith, after which they were transported south at night on hundreds of trains.

The article also suggested, “What a surprise is in store for the Germans when they find themselves faced on the west with hordes of Russians, while other hordes are pressing upon them from the east!”

Officials during that time did not confirm or deny the reports. But, due to the mystery of the great possible existence of the Cossacks and the secrecy of the war efforts on both sides, there was reason to believe the reports out of paranoia. Other reports surfaced collaborating the initial rumors of the massive force of Russian warriors.

One witness claimed to have seen 10,000 Russian warriors marching along the Embankment heading towards London Bridge Station. A rail porter at Durham reported that he found an automatic chocolate machine jammed by a rouble.

Another man who reportedly boarded a ship from Archangel said the saw 2,500 Cossacks on board as well on a route to France. He also said that he took several pictures of himself and the men. He claimed to have submitted the photographs to his local newspaper but was prevented from publishing them due to censorship.

Meanwhile reports in Malvern claimed that a Russian jumped off a train to order 300 “lunchsky baskets”. A woman near Stafford further corroborates the story saying she saw men numbering by the hundreds in long grey overcoats next to their train stretching their legs.

The stories do not end there. At Carlisle, shouts for “vodka” were reported to have resonated from a train. Another report said that men in tunics numbering around 250,000 were sighted near the Astrakhan area southwest of Russia marching pass a town in North Wales.

The press from the U.S., which enjoyed freedom from censorship, reported extensively the said sightings of the “Cossacks”.

For example, the New York Times pegged the number of Russians at 72,000. The men were said to have traveled from Aberdeen to Grimsby, Harwich and Dover, and then towards Ostend.

The British soldiers who are at the front also heard of the stories via the letters of relatives and loved ones from home. One newspaper dispatch from Belgium even featured the arrival of the Russians at the front.

Brigadier-General John Charteris, a senior intelligence officer, also heard of the reports. After making inquiries, he found that there was no truth to the rumours.

The Germans, however, believed the reports. In a panic due to the “official news of the concentration of 250,000 Russian troops in France”, the Kaiser and senior headquarters staff left France and retreated altogether on September 7 as reported by the Continent.

The Germans also made a move to retreat their troops south east as it neared Paris to avoid encountering the Cossacks. The moving of German troops gave the Allies time to plan well their advance at the Battle of the Marne by the mid September. The Russian rumour played a significant part in leading on the Germans to a very major tactical military error. Subsequently, the conniving reports gave way to the victory of the Allies. Senior military officials have recognized it as a factor in the successful war efforts that followed.

The Germans, anticipating the Russian assault that never took place, were forced to give away two divisions to guard the Belgian coast against the reported approaching Russians. This eventually weakened their defenses for the forthcoming Battle of the Marne.

After the victory of the Allies at the Marne battle, the British Government issued an official denial of the existence of the Russian troops. However, the rumour grew with persistence. This time, reports insisted that the denial was part of the continuing plot to dupe the Germans.

Dr. Clarke researched on where the rumours started and what triggered the spread of such outstanding myth. He traced it on August 24 when the railways around the country were a site to lengthy hold-ups.

The hold-ups were imposed to give the reservists time to move from barracks around the country to embarkation points on the south coast. The trains moved on hand signals. They traveled at night with orders to keep the blinds down.

Among the battalions involved was the 4th Seaforth Highlanders with members who are mostly Gaelic-speaking. Their appearance and foreign language gave rise to speculations of Cossacks being transported.

In one Midland station, a porter claimed to have asked a group of these soldiers where they were from. He was said to have misunderstood the reply of “Ross Shire” as “Russia”.

Adding to the rumours are arrival of some Russian officers in Britain who traveled from Archangel to Scottish ports. The officers were accompanied by a number of soldiers. They were in Britain to organise supplies for their troops. They also served as attaches to various military staffs. Their presence further signaled confirmation to the unknowing spectators and fueled the rumours further.

Another culprit to the spread of the wild rumour was a telegram sent from a shipping agent in Aberdeen to his London headquarters. The large consignment of Russian eggs must have been mistaken for Russian troops as the message only said “100,000 Russians now on way from Aberdeen to London.”

The rumours would not have reached to such propensity had the British intelligence service and British agents not played the part of igniting and instigating the stories. They deliberately tried to feed false intelligence to their German counterparts.

MI5 were able to intercept the letters and telegrams sent back to his handlers by Carl Lody, a German spy assigned in Britain. However, the MI5 allowed the stories of the build-up of Russian troops from Lody to be sent to Germany.

Dr. Clarke said, “It was an accidental rumour, which turned into a massive delusion. The authorities just let it run, and it was seem to have played a role in the war.”