Early in WWII, the Germans were marching through Europe, and Britain was next. On July 16, 1940, the British prime minister, Winston Churchill, declared, “Set Europe ablaze!” Thus was born the Special Operations Executive (SOE) to do just that.

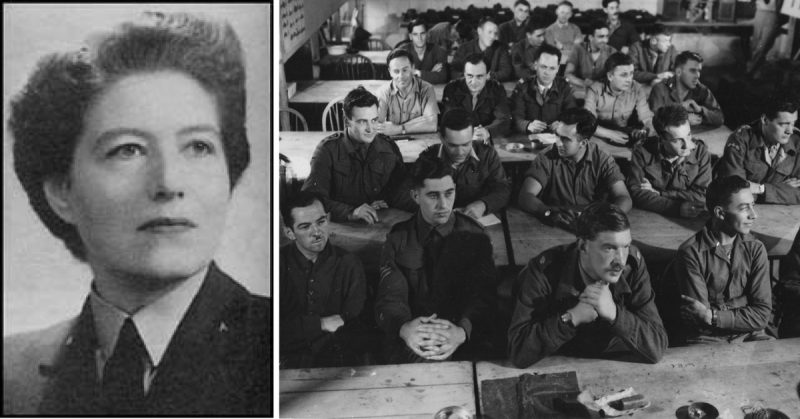

Vera Maria Rosenberg was born on June 16, 1908, in Galați, Romania to a German-Jewish father and a British-Jewish mother. She studied languages at the prestigious Sorbonne in Paris and went to finishing school in Switzerland before training to be a secretary in London.

Sadly, her father went bankrupt in 1932 and died shortly after, forcing her to return to Romania. By 1937, however, Romania’s new government were markedly pro-German and anti-Semitic. Being a smart woman, Rosenberg decided she was probably better off back in Britain. She began using her mother’s maiden name around that time.

Her gilded life had served a purpose, however. Her family’s wealth had enabled her to mingle with the upper crust – including several European diplomats. In 1940 she traveled to the Netherlands with money to bribe an Officer from the German military intelligence or Abwehr.

Her cousin was anxious to escape German-occupied Romania and needed a passport. With help from the Belgian resistance, she got her cousin out and made her way back to Britain. Atkins involvement in the escape was only discovered after she died when a British reporter investigated her life – a reflection of just how secretive she was.

She worked for a time as a translator and an oil company before joining the SOE as a secretary in 1941.

Churchill wanted to set Europe ablaze with sabotage operations to give Britain a fighting chance. Atkins’ language skills, intelligence, and composure got her a promotion – assistant to section head Colonel Maurice Buckmaster.

Buckmaster lead the SOE’s French and Belgian section. Between 1941 and 1944, he smuggled 366 agents into France. There they financed and armed the French resistance for sabotage operations and gathered intelligence on the Nazi occupiers. They paid a high price – 118 agents died. Despite knowing the risks, they all volunteered to go.

Atkins played a major role in choosing who went. Once satisfied they stood a chance, she escorted them to the Tempsford airstrip in Bedfordshire and waved them off as they flew across the Channel. It was not easy. Atkins later claimed that it caused her enormous stress to realize she was likely sending them off to their deaths.

Among them were 37 women trained as couriers and wireless operators. Atkins’ job included ensuring they were appropriately clothed; giving them proper documentation; making sure they knew their target area well; seeing to it their families received their pay, and sending coded messages via the BBC so agents in the field knew how their families were doing.

Sadly, the SOE made mistakes, especially in the early years. Henri Déricourt was an SOE agent and former French Air Force Pilot who flew the agents into France. He may also have been a Nazi double agent. Whatever the case, the Germans captured SOE agents, sent false information back to Britain, and even defrauded the SOE of money and supplies.

Despite the warning signs, Buckmaster refused to believe his spy network had been compromised. In March 1941, the Abwehr forced a captured SOE radio operator to send misinformation back to his headquarters. He did so but also transmitted a code which meant he had been captured and was under duress. It made no difference.

Buckmaster accepted the information as valid, ignoring the extra code. As such, he received the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (OBE) award and the French Croix de Guerre after the war. It was also after the war, however, that he realized how badly he had let the SOE be compromised and how many people he had sent to their deaths.

While he could let it go, Atkins could not. By February 1944, she had become a British citizen and denied ever having made any errors in the SOE, stressing the agents were volunteers. She joined the British War Crimes Commission to gather evidence for the prosecution of war criminals.

After the war she visited concentration camps and interrogated guards, attempting to find out what had happened to the 118 missing persons she had sent off. Hugo Bleicher, the Abwehr officer who had broken most of the SOE agents, claimed she was the most formidable interrogator he had ever met.

Atkins even questioned Rudolf Hess, Commandant of Auschwitz. Asked if he was responsible for killing 1.5 million Jews, Hess replied no. The correct figure, he insisted, was 2,345,000. He was convicted at the Nuremberg Trials.

In 1947 she was told the SOE was to be disbanded, and her search could no longer be funded. Using her contacts in MI6 (British Military Intelligence, Section 6), she obtained funding to continue her work.

She continued searching through documents, claiming she “could not just abandon their memory.” Atkins went on to explain “I was probably the only person who could do this. You had to know every detail of the agents, names, code-names, every hair on their heads, to spot their tracks.”

Although she never found them all, her work became the basis of the Roll of Honor at the Valençay SOE Memorial unveiled on May 6, 1991, in Loire, France. It lists 91 men and 13 women who gave their lives to free the French and may have given Atkins some peace when she finally passed away on June 24, 2000.