The instinct to make large fortifications goes back thousands of years.

In Britain, during the Iron Age (about 800 BC to AD 100), they made giant hill forts like Maiden Castle in Dorset, England that ended up covering 47 acres.

These hill forts were primarily earthworks with embankments, ramparts, and ditches.

In the 11th Century, these earthworks began to evolve into wooden motte and bailey forts, which eventually were rebuilt or fortified with stone. These buildings were the beginnings of what we would come to think of as traditional castles.

Sea forts were an even later invention.

The idea was to ward off any invading army before they could reach your shore.

By World War Two, large permanent fortifications were seen as mostly obsolete and not suited to the fast flowing pace of modern warfare.

The supposedly impregnable Belgium fort of Eben-Emael and the huge 280-mile long French Maginot line proved that large static defenses could be quickly over-run or bypassed.

But sea fortifications were going to prove their worth, particularly around the Thames (London) and the Mersey (Liverpool) estuaries, where there were two main problems.

Firstly, there was the danger of German aircraft mining the entries to these ports, thus disrupting a significant amount of shipping that was bringing in vital war material.

Secondly, enemy bombers were using these rivers as landmarks to navigate themselves into the center of these cities.

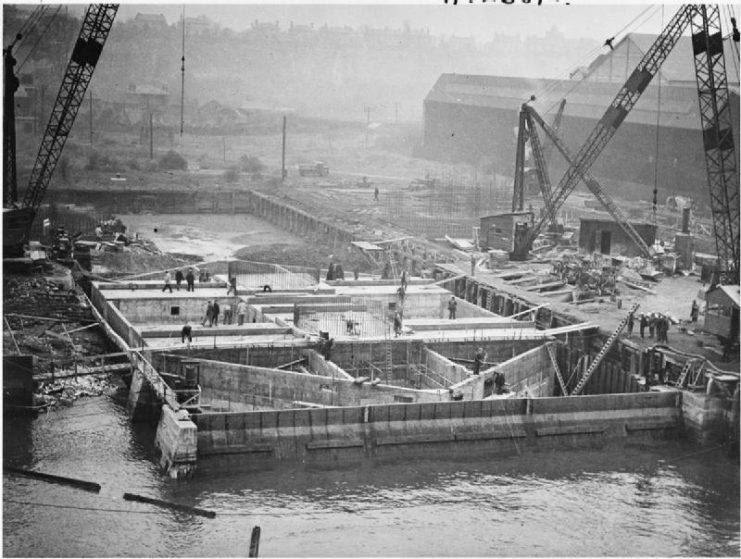

Guy Maunsell was a civil engineer and an expert in the new field of prestressed concrete. He had served in the Royal Engineers in World War One.

As a result, he had a good understanding of an integrated approach to design and construction coupled with a comprehension of the unique needs of the military.

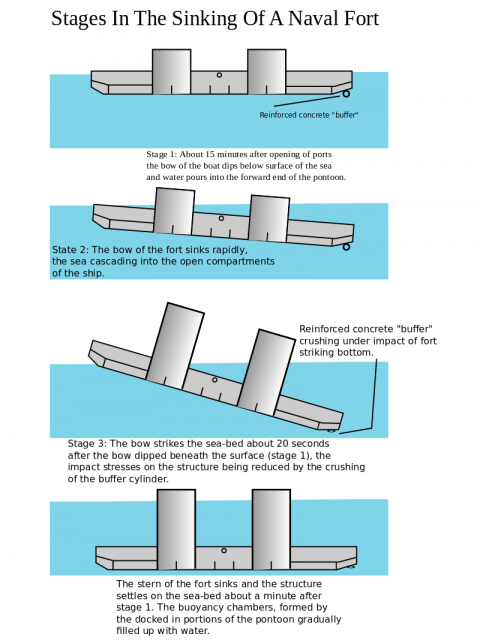

He proposed a series of fortified sea towers armed with anti-aircraft guns be built on land and then towed out and placed in strategic positions along the mouth of both estuaries.

In the end, he developed two distinct designs, and the resulting constructions were simply called “Navy” or “Army” forts, depending on which service was running them.

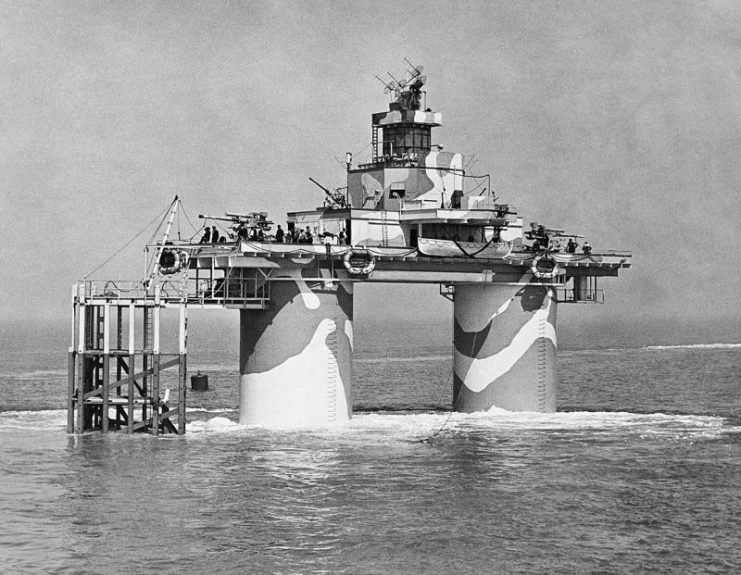

Four of the new structures became Navy Forts run by the Admiralty. Construction started on them in 1942, and they were all completed by 1943.

Two were placed in the Thames estuary in south-east England, while the other two were placed nearby, slightly further up off the Essex coast. They were named:

- Rough Sands

- Tongue Sands

- Knock John

- Sunk Head

These forts consisted of a steel platform over 100 feet (30 meters) long, that was perched on top of two giant 60 foot (18 meter) reinforced concrete towers. These towers were 24 feet (7 meters) in diameter and were divided into seven floors each consisting of:

- Crew Quarters

- Dining Room

- Ammunition Bunker

- Supplies

- Storage

- Fresh Water Tanks

- Generators

On the steel platform itself, there were two heavy 94mm and two light Bofors 40mm anti-aircraft guns.

The 94mm could fire around 15 rounds a minute up to a height of 45,000 feet (13,716 meters). The 40mm could fire at a rate of 120 rounds a minute up to a height of 23,500 feet (7,162 meters).

The maximum ceiling of a German Heinkel III was only 21,000 feet (6,400 meters).

The fort was also aided by a large and complex radar installation perched on the very top of a tall central bunker which housed the following:

- Command Centre

- Medical Facilitates

- Officers’ Quarters

The whole structure weighed around 4,500 tonnes and had a crew of 120 sailors.

Then there were the Maunsell Army forts which were run by the Army. The construction on these forts started a little earlier than the Navy ones, the first one beginning in October 1941.

Each fort was actually a cluster of seven individual giant boxed steel structures, on top of huge reinforced lattice girders and connected by walkways. They were very much larger than the Navy Forts.

Each of these forts carried four heavy 94mm and two light Bofors 40mm anti-aircraft guns, so they were slightly better armed than the naval-designed forts.

These forts consisted of:

- Control Centre

- Several Barracks

- Several Dining Areas

- Secure Ammunition Bunker

- Multiple Storage Rooms

- Dedicated Searchlight Tower

They housed a crew and garrison of 400 soldiers.

There was talk of constructing more of this type of fort off the Humber estuary as well as in the seaports of Portsmouth, Rosyth in Scotland, and Belfast and Londonderry in Northern Ireland. But this never happened.

Three of these Forts were based in the Liverpool Bay and were called:

- Queens

- Formby

- Burbo

Originally there were going to be a further three more forts in the Liverpool Bay Area, but they never materialized.

Three more were placed at the mouth of the River Thames:

- Nore

- Red Sands

- Shivering Sands

So, were these forts effective?

It was reckoned that, during World War Two, the Thames estuary forts shot down 22 German aircraft and around 30 V-1 flying bombs.

They also achieved one naval victory: the sinking of a Kriegsmarine E-boat (a fast torpedo armed light attack craft).

With regards to the Liverpool Bay series of forts, there is no record of them inflicting any casualties on the enemy.

This may of all seem ineffective considering how much time, effort, and resources were put into the Maunsell project. But perhaps their true value was more as a deterrent, as well as serving as useful intelligence-gathering posts.

And their fate? By the early 1950s, all the forts in both locations had been decommissioned by the Ministry of Defence.

There was no attempt to destroy or dismantle them. They were simply abandoned by the military.

All three Liverpool bay forts were demolished by 1955 as they were deemed to be a hazard to shipping.

Two of the four Navy forts in or around the Thames still survive today.

There was an unsuccessful attempt to set up an independent nation on one of these remaining forts. The nation was called the Principality of Sealand but was never officially recognized by any other country as a nation.

At various stages during the 1960s, both types of forts were used as pirate radio stations. But this was outlawed by the Marine Broadcasting Act in 1967.

As for the Army ones, five of the six forts still exist today in various states of disrepair.

There is an effort called the Redsands Project whose objective (as of 2018) is to renovate the Redsands Army Fort and turn it into a museum since it is considered to be in the best condition of the surviving forts.