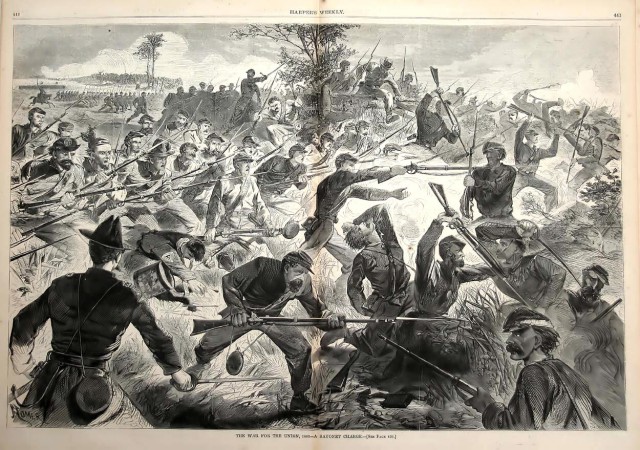

The First World War was devastating in its scope and utterly unlike what national leaders expected. As such, it was seen by many as an event of unpredictable and unprecedented horror.

But in reality, many of the things that made World War I distinct, both in its horrors and in its innovations, had happened before. Three wars, in particular, showed what was coming.

The French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars – 1792-1815

The most obvious connection between World War I and the Napoleonic Wars lies in their scale and the networks of treaties involved. Ranging all the way from the Atlantic Ocean to the Russian steppes, these wars drew in almost every nation in Europe. Though there were precedents in the Seven Years War and Thirty Years War, the wars against Napoleon and his predecessors reached further than ever before.

The list of nations involved is telling. France, Russia, Austria, Britain and Russia were all major players. Prussia’s prominent role in the war was a major turning point for that nation, triggering its rise to dominance and the eventual emergence of Germany.

But the most important innovation of these wars came not in the nations involved, but in the men who fought. 23 August 1793, a date few now remember, was one of the most important in military history. On that date the French National Convention, faced with vastly superior enemies on their doorstep, voted to introduce the levée en masse, the first mass conscription in history.

From now on, the wars of Europe’s nation states would be fought not by professional soldiers but by whole populations of forced recruits. The mass conscriptions that saw a generation dead in the trenches of World War I began with a single vote in August 1793.

Other nations would later follow the French model, in part to counter French numbers. With more nations and more men under arms than ever before, European warfare reached a new and devastating scale.

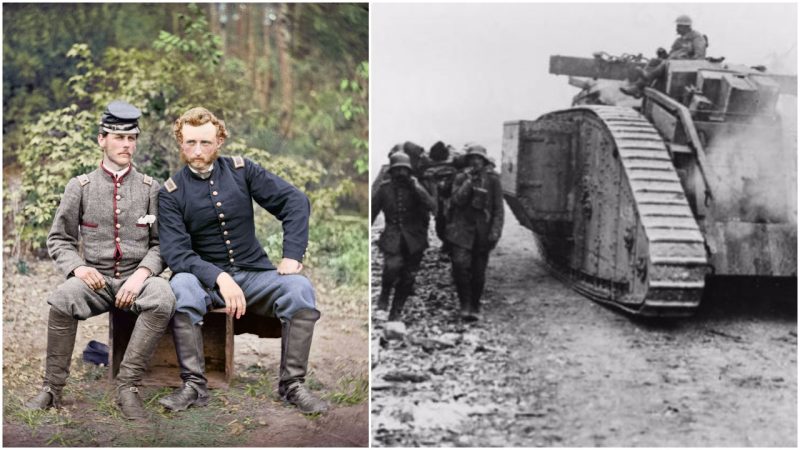

The American Civil War – 1861-1865

By the 1860s, many of the technologies with which the Great War would be fought were in place. Devastating artillery, breech loading rifles, and railway supply lines had all been used in war. The industrial revolution was in full swing, and a strong industrial base was vitally important to sustaining a war.

From 1861-1865, the world would see what happened when two determined forces fought with the full might of an industrial war machine.

The battlefields of the Civil War were more like those of Napoleon than those of the Great War. The continued use of cavalry charges and infantry lines set an example that would mislead the commanders of 1914. But the great sieges of the late stages of the war, such as those of Atlanta and Richmond, showed what was to come. Men hunkered down for weeks on end in deeply dug trench lines, while shells bombarded both sides of the line. Assaults faltered in the face of these defensive works and the firepower hidden within them. Trench warfare had arrived.

The Civil War also introduced the idea that war had to be total. It was not enough to outmanoeuvre the enemy in a few places. Warfare between industrialised nations meant grinding away at the enemy’s army and economic base, whittling them away until they had nothing left to fight with. This was the strategy of General Ulysses S. Grant during the Overland Campaign and beyond. Though civilians were not targeted, everything else was. Railways were ripped up and their tracks twisted beyond use; farms and factories were destroyed. The sort of economic ruin that would force Germany to surrender in 1918 also brought the Confederacy to its knees fifty years earlier.

Despite its deep and painful divisions, the Civil War also forged a powerful sense of American nationalism, especially in the north. The relative importance of national spirit, as opposed to identification with a single state, created a patriotism that would support America’s intervention in Europe in 1917-18.

The Franco-Prussian War – 1870-1871

The Franco-Prussian War was the third and final in a series of wars leading to German unification. Rather than unite Germany by conquering their neighbours, the Prussians sought to unite the fractured German territories through common cause.

Though ruled by King Wilhelm I, Prussia’s real mastermind was the King’s leading minister, Otto von Bismarck, one of the most remarkable politicians of the 19th century. Bismarck created diplomatic crises that triggered wars against Denmark (1864) and Austria (1866). These gave the alliance of separate German states a sense of power and unified purpose.

Finally came the Franco-Prussian war.

Like the American Civil War, the Franco-Prussian War saw the use of military technology that would be put to greater effect during World War I. In particular, devastating long range artillery barrages were seen. French attempts to field an early machinegun were far less effective, due to its tactical misuse and lack of adequate training before its deployment.

The Prussians made effective use of the railways to quickly mobilize their troops and outmanoeuvre the French. The Schlieffen plan used in 1914 assumed that they could do this again. The swift defeat of the French also shaped that plan, leaving the Germans confident of an easy win in the west. But this took no account of French improvements in the intervening years, and so 1870 left the Germans with an over-confidence that would be their undoing in 1914.

Most importantly though, the Franco-Prussian War set the stage diplomatically for World War I. The nation state of Germany was officially born on 18 January 1871, amid the grandeur of the Hall of Mirrors in occupied Versailles. A strong, powerful and confident nation had been created, upsetting the balance of power in Europe. The Treaty of Frankfurt, which ended the war on 10 May 1871, took most of Alsace and parts of Lorraine from the French and gave them to the Germans. This, together with the sting of defeat, stirred French resentment and ensured tension between the two nations. It was that tension which turned a Balkan conflict from a war in eastern Europe into one that engulfed the whole continent.