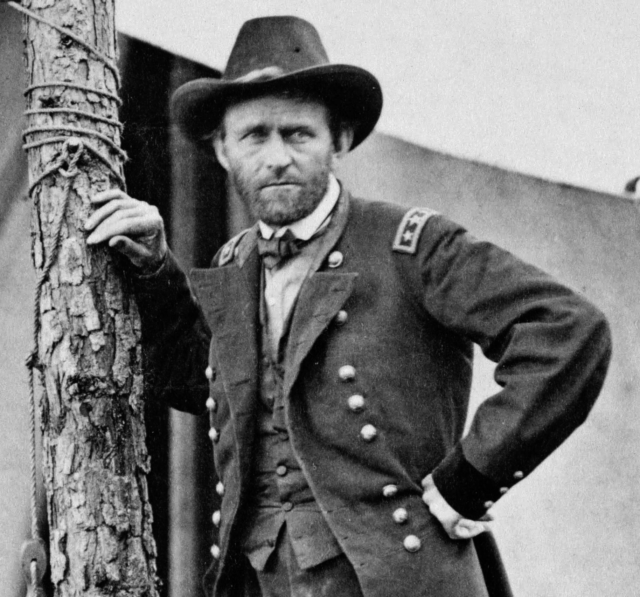

The Duke of Wellington and Ulysses S. Grant were two of the greatest generals of the 19th century; arguably in the whole of history.

Their periods of brilliance were fifty years apart and on different continents. Wellington showed his prowess against Napoleon in Europe from 1809 to 1814 and took part in the first great wars of mass mobilization. Grant spearheaded the Union victory in North America in the 1860s at the dawn of industrialized warfare.

Their armies were comparable both consisting of massed lines of infantry supported by cavalry and cannons. There were many similarities between the two men.

A Gift for Sleep

Sleep does not come easily for a commander on a campaign. Stresses and responsibilities keep them awake. The noises of military life run long into the night. Rough beds in unfamiliar places do not make for a comfortable life.

The Duke of Wellington was famous for his capacity to go without sleep. A fastidious commander, at the peak of his campaigns he regularly sat up until three in the morning writing orders, then rose only a few hours later ready to lead his men.

In some, such behavior might show they struggled to sleep. Not so Wellington. He was famous for his ability to sleep soundly when given the opportunity, no matter the circumstances. On the night after Waterloo, he gave up his bed to a dying comrade and slept soundly on a couch.

Grant had no trouble sleeping while on a campaign. In March 1863, he wrote that “I never sit down to my meals without an appetite nor go to bed without being able to sleep.” War apparently suited him physically and emotionally. He wrote of his health that he was “better than I have been for years,” as he fought for the soul of his country.

Lack of Display

Wellington fought against one of the most ostentatious leaders in history. Napoleon loved the pomp and ceremony of military tradition; even inventing some traditions himself. His career was built upon self-promotion, and he never shied from an opportunity for display. From the grandeur of his coronation to the speeches to his troops to making a show of talking with ordinary soldiers.

Rather than fight fire with fire, Wellington went the other way. He looked down upon Napoleon’s showmanship as insubstantial bluster. He never gave speeches to his men. As he said, “what effect on the whole army can be made by a speech since you cannot conveniently make it heard by more than a few thousand men standing about you?”

Grant showed even less taste for display than Wellington. One of his subordinates commented that “If he had studied to be undramatic he could not have succeeded better.” There were no speeches, no dramatic moments, no riding close to the action to share danger with his men. There was a minimalism to what he did in front of the soldiers, earning their respect through calmness rather than showmanship.

Dressing Down

This lack of display extended to the uniforms that both men wore.

Grant was one of the least conservative dressers of his officer corps. He habitually wore a private’s coat with his general’s stars pinned on, creating a visual connection between him and his men. He dressed quickly and stayed in the same suit all day, not wanting to waste time dressing for dinner or other occasions. His tendency to fidget did not help – he wore holes in his cotton gloves by whittling.

Wellington took more pride in his appearance, but also kept it simple. He wore “regimentals” – a scarlet coat and heavy saber. Awarded all manner of medals and positions, he refrained from displaying these on his uniform. He wore a greatcoat to protect him from the weather making his appearance all the more ordinary and muted.

Feel for the Land

Both men had a gift for recognizing the nature of the landscape they fought in and using it.

Wellington, grasping the topography of an area could usually outguess his fellow officers on what lay behind the next hill. One of his most successful battlefield maneuvers came from using the land. He had his troops hide on the rear slope of a hill, the ground protecting them from enemy gunfire and making it harder for artillery to hit. Then they rose as the enemy approached, appearing from behind a ridge to fire on attackers.

Fifty years later Grant was also obsessed with the landscape and how to use it. He had the advantage of five decades of development in the art of map making. He was trained in mapping at West Point, collected maps, and studied them in detail. It was said he could look at a map once and remember all the details.

Shot by Musket Balls

Wellington liked to lead from close to the front, putting himself at risk from gunfire in return for better control of the battle. He repeatedly came close to death due to artillery and small arms fire. Bullets left holes in his clothes and equipment, and he lost several horses. His closest call came in 1814 when a French musket ball hit the buckle of his sword belt at Orthez. The buckle probably saved him from death, but it left a bruise on his thigh.

Grant avoided being close to the action when possible, but he also had close calls. At Shiloh in 1862, a musket ball hit the metal of his scabbard, breaking his sword.

From their grasp of a strategy to the little details of battlefield action, these taciturn commanders shared a great deal in common.

Source:

John Keegan (1987), The Mask of Command;