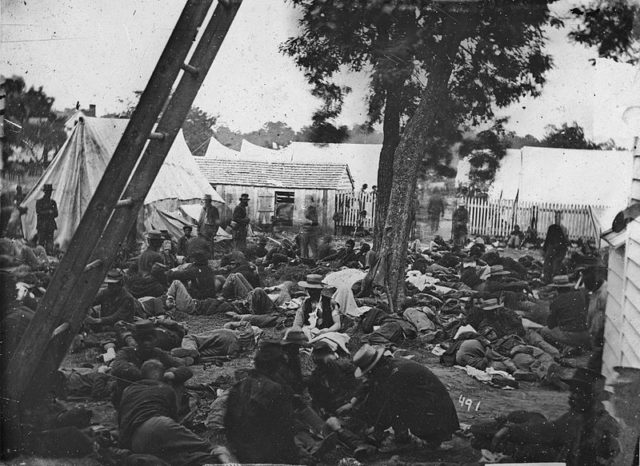

Disease accounted for the deaths of 65% of Union soldiers and 62% of Confederates during the Civil War. Those high numbers beat out all other forms of death. Not all soldiers afflicted with diseases died, but some did carry their diseases home where they – and often their family – suffered with them for years afterward.

Army Itch

Also known as Camp Itch, this malady was not simply annoying. It was fiery, painful, and maddening.

“I had a bad case of the itch… it became very bad; so much that my hands were swollen, and my fingers stood apart. Sores and yellow blisters came between them, and they ran corruption. I could scarcely touch anything, my hands were so sore.”-Pvt. Milton Asbury Ryan, Co. B, 14th Mississippi, CSA

Some doctors said it was scabies, and if often was. However, there were cases in which no scabies, and no other known cause (no “animalcules”), was found. They did all believe that whatever the cause, the lack of bathing and other forms of hygiene was a big contributor.

One doctor said of his attempt to cure it, “We have used the medicine internally and externally, the disease still rages infernally, and it looks to me as though it will last eternally.”

Gray-backed Louse

The simple louse might not seem like much of a disease, but they were responsible for making many soldiers very sick with deadly diseases like Typhus. They were annoying, itchy, and a constant source of irritation for soldiers who were already weary with hunger, dirty bodies, sleeplessness, and other ailments.

Some cases of Army Itch may have been from the gray-backed lice. The lice caused long red welts that burned and itched terribly.

There was a little joy to be had with the lice, though. For one, Union soldiers used its name in reference to the similarly gray-clad Confederate soldiers. Secondly, men on both sides of the war used the lice for entertainment. They put two lice in a makeshift ring and watched them fight each other. Some held races between lice and placed bets on the results.

Diarrhea/Dysentery

Diarrhea was a very serious condition during the Civil War. It often became chronic, and in several cases lasted for many years.

Most soldiers had diarrhea most of the time. It led to dehydration and more serious diseases and never left much energy for marching, much less fighting for their lives.

Dysentery differs from diarrhea in that it includes blood and also causes high fever and severe abdominal pain as well as the feeling that the sufferer has never fully emptied the bowels. Dysentery is also deadly – it accounted for 45,000 Union deaths and 50,000 Confederate.

Malaria

Malaria affected how the war was fought. Because untreated malaria was fatal, the Union tried to avoid the South during its “Sickly Season” – the months between May and September. Malaria is spread by mosquitos and mosquitos love the hot, humid conditions of the South. To suppress the South’s ability to treat the disease, Union blockades prevented quinine from reaching Southern ports.

Even though the Union tried to avoid it, that didn’t mean they always succeeded. Over 1 million Union soldiers contracted malaria during the Civil War. They suffered enlarged spleens, very high fevers, chills, congestion, nausea, headaches, and the shakes. It was often fatal.

Typhoid fever

One out of every three soldiers who contracted typhoid died of it – 65,000 in all, fairly evenly divided between North and South. The scary thing about the disease was that soldiers could carry it without showing symptoms, or soldiers that had it previously spread it after thinking they had long been cured.

The disease is caused by salmonella, and it mimics the symptoms of dysentery with the addition of a flat, pink rash and nose bleeds. It goes beyond dysentery symptoms when it causes perforation and bleeding in the intestines, encephalitis in the brain, inflammation in the gall bladder, and abscesses in other internal organs, including the heart and bone tissue.

Angel’s Glow

The Battle of Shiloh was followed by two days and two nights of rain. The effect on wounded soldiers is more than fascinating. The wet conditions caused their wounds to glow – enough to cause a faint light around them.

What’s more interesting is that the soldiers whose wounds glowed had a better survival rate. How and why the wet weather caused the glow remained a mystery until the young son of a scientist visiting the battle site in 2001 asked her if the glow could have been caused by a luminescent bacteria she had been studying. The boy took it upon himself to find out, and he was right.

The fun part sounds like a good ole’ Southern yarn . . . The bacteria thrives in the guts of nematodes. These bacteria eat other bad bacteria – which is how the soldiers healed so well and so quickly.

Pneumonia

Pneumonia was the third most common cause of death during the war, accounting for 24% of all deaths. Even Stonewall Jackson couldn’t conquer it.

Antibiotics were still unknown, so as the condition progressed, bacteria would leak into the bloodstream, causing sepsis and then death.

Not only did they not have antibiotics, the treatments they did use made the disease worse. Rather than “plenty of fluids” some doctors still practiced blood-letting and more progressive doctors gave medicines that were meant to clean forcibly out the intestines as well as medicines to induce vomiting. So basically, they dehydrated the patient in one way or another until he died.

Chickahominy Fever

It’s unknown exactly what this fever really was, but the assumptions range from malaria to typhoid to even dengue fever. What is known is that it was likely mosquito-borne.

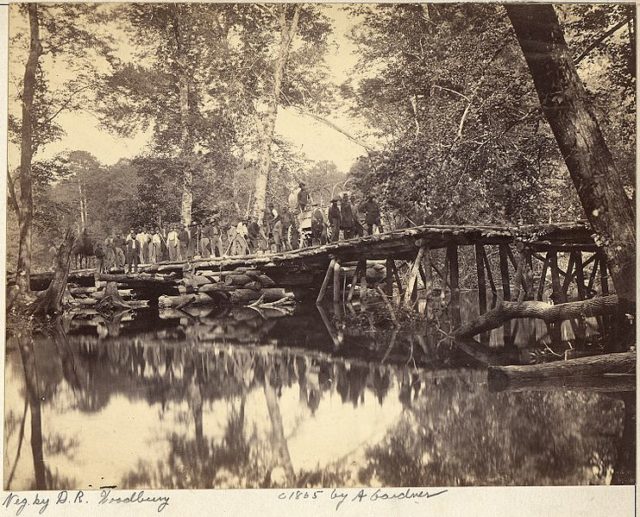

The Chickahominy River in Virginia is surrounded by swamps – the perfect breeding ground for horrifying diseases carried by insects. Soldiers camped out along it during the Peninsular Campaign of 1862 became very ill from this terrible fever.

This version of what seems like both a typhoid and malarial illness included a brown fur on the tongue to distinguish it from other known diseases of its type. After the war, it’s official name became Typhomalarial fever.