The foremost Union commander of the American Civil War, Ulysses S. Grant led his nation’s armies to a victory that united the fractured union. As a leader, he understood the age he fought in and the men he led in a way few could match.

So what was distinct about his leadership?

Rejection of Showmanship

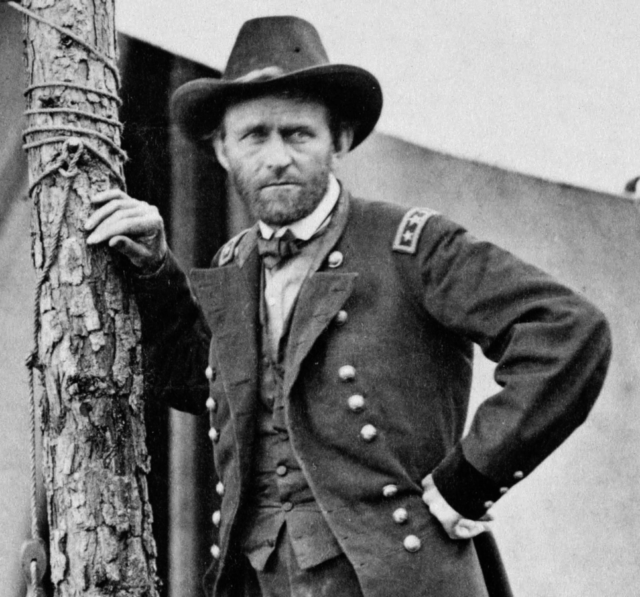

One of the most famous images of Grant is a photograph taken at the Battle of Cold Harbor in 1864. Wearing an infantryman’s coat with his generals stars pinned on the shoulder, a plain hat, and a week’s worth of beard, he is seen leaning casually against a post, a distant look in his eyes. The unassuming look was characteristic of Grant’s style.

According to one of his subordinates, “If he had studied to be undramatic, he could not have succeeded better.” Grant did not go in for big speeches or dramatic gestures. There was a minimalism to what he did in front of the soldiers, earning their respect through calmness rather than showmanship. It was the perfect style for the man leading an army of the people in a democratic state.

Staying Back from the Lines

Grant served at the cusp of a huge change in the way generals behaved. During the American Civil War, speedy communication over any distance was difficult. To direct their troops, commanders needed to be at the battle.

On the other hand, leading from the front line was an incredibly risky undertaking. Fifty years earlier, artillery fire had killed several commanders during the Napoleonic wars, including Sir John Moore, one of Britain’s finest generals. Since then, the range and accuracy of firearms had improved, making it even more dangerous to get within sight of the enemy.

Grant found the perfect balance. He was at the battle but steered clear of the fighting. It was a rare accident when, at Shiloh in 1862, he was close enough to danger for a musket ball to break his sword.

Balancing Discipline

There were new challenges to enforcing discipline in the armies of the Civil War. Professional soldiers had fought most of the previous wars of the United States. They were men who had chosen an army life, accepting its hardness in return for regular pay and work satisfaction.

The soldiers of the civil war were different. They were a part of massive armies made up mainly of volunteers rather than professionals. They would not all respond well to strict discipline.

Grant enforced firm discipline, particularly on sensitive issues such as unauthorized looting. However, he did not press his men so hard that they might break. Instead, he relied on other tools to turn his volunteers into soldiers.

Focus on Drill

There was another way to enforce correct behavior in his troops, and that was the drill.

Drilling was the most important part of training in the age of musketry. It allowed hundreds or even thousands of men to march and fire as one. It also instilled a sense of unity and purpose.

Early in the war, Grant had seen what happened when drill-based discipline was weak, and good order broke down. He placed heavy emphasis on the drill to make units function properly.

Letting Men Have Their Head

As with enforcing discipline, Grant understood there were limits as to how far he could make his volunteer army do what he wanted. If he fought them every time their will and his clashed, then he would demoralize the troops. To avoid it, he picked his battles, occasionally letting the men have their head.

An example was at Vicksburg. Grant knew he would have to dig in for an extended siege, but his soldiers wanted to attack straight away. He let the attack happen. Men were killed in a bold but futile attack. It was a loss he always regretted. Afterward, the troops were willing to settle down and pour their energy into digging and waiting out the siege.

A Feel for the Land

Grant was fascinated by the landscape and how he could get the most out of it. He was trained in mapping at West Point, collected maps, and studied them in detail. It was said he could look at a map once and remember all the details.

It was reflected in his early campaigns. His knowledge of the waterways of the Mississippi basin proved invaluable in moving troops and supplies around the region.

Baseless War

His attachment to the landscape and to working within its limitations could easily have become the factor that limited Grant. Instead, he rose above it.

As the war ground on, he realized that maintaining supply lines was limiting him. By tying himself to the rivers to ensure supplies, he was limiting his ability to maneuver. In response, he developed a model of baseless war. Early experiments showed him that his army could easily live off the land in the fertile American south. Supplying himself through foraging and raiding on a vast scale became the hallmark of his campaigns, freeing his troops to move where he wanted.

Total War

Influenced by the need for supplies and the merciless war in the west, Grant was one of the men who turned the Civil War into a total war. He expanded upon his raiding using the logic of economics and morale. By destroying railroads and devastating farmland, he deprived enemy forces of supplies and communications. He demoralized and dispersed the civilian population, reducing their willingness and ability to support the war. His army tore up train tracks, took food from the surrounding farmland, and burned what they could not take.

Grant understood he was fighting a new sort of war. His leadership was marked by an understanding of how to relate differently to his men, the enemy, and the land.

Source: John Keegan (1987), The Mask of Command