It was cold at the turning of the year in Murfreesboro, right in the middle of the state of Tennessee. The little town nestles under a crook in the arm of the Stones River, near where the water rushed and chattered over a long shallow ford. The Civil War had raged across the country for nearly two years. At the end of December in 1862, the Union force called the Army of the Cumberland was maneuvering into position to challenge the Confederacy’s Army of Tennessee.

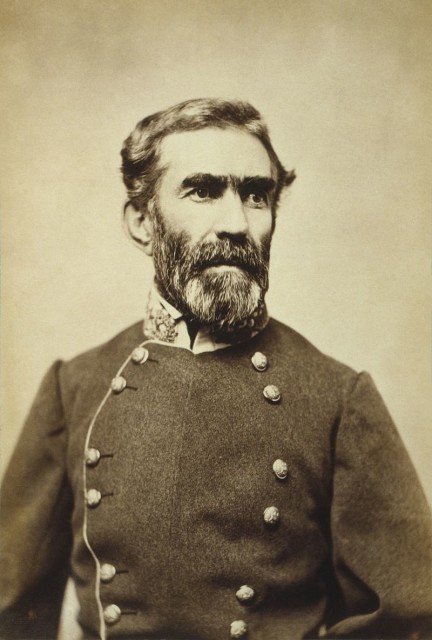

The Confederate troops were commanded by Braxton Bragg, a tall, thickly bearded, sad-eyed veteran of the South’s campaigns. His army numbered around thirty-five thousand men, cavalry, cannon, infantry, and skirmishers. They had been encamped north of Murfreesboro for a month when the Union forces finally arrived.

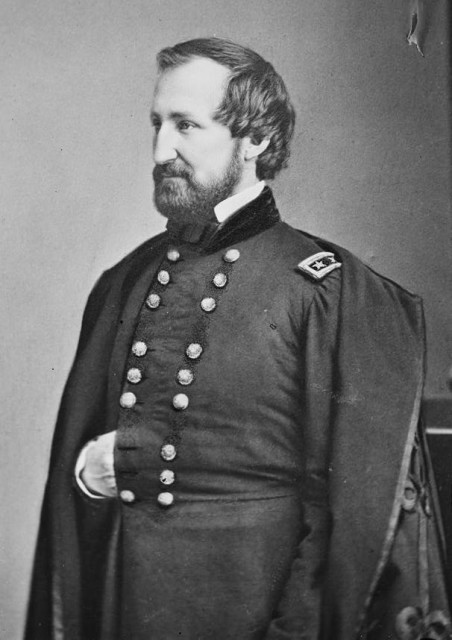

General Rosecrans was in command of the Union Army of the Cumberland, which out-numbered Bragg’s force by nearly ten thousand men. They had marched the long road south from Nashville to Murfreesboro, and by New Year’s Eve in ’62 they had deployed in a line stretching four miles long facing the Confederate Army. Overnight, the armies were camped so closely that they could clearly hear and see each other.

Each army was well equipped with musicians, and both sides began to play and sing competing songs under the starry sky. After some time, one band struck up a tune which resonated with both sides, and the musical competition became an alliance. Thousands upon thousands of voices from both sides joined together in a song everyone knew. ‘There’s no place like home, boys’ they sang, ‘There’s no place like home.’

Both sides were readying themselves to attack in the morning, but Bragg struck first. The left wing of the Confederate army swept forward in a huge wave toward the Union lines. Ten thousand men marched swiftly toward their enemy, pausing only to unleash vast barrages of rifle-fire against them.

The Union soldiers were not prepared for the sudden onslaught, and when their enemies closed the distance and charged to fight hand-to-hand, they were driven back, yard by yard, three miles from their original position. Their losses were terrible, but they fought for every foot of ground they gave. Cannons began to fire from both sides, and the second wave of Confederate soldiers began to advance on the disintegrating Union right.

General Rosecrans scrambled reinforcements toward the fighting, riding to and fro at a gallop across the battlefield. He was covered in blood, and everywhere he went he cried out in strident tones to his men, encouraging them.

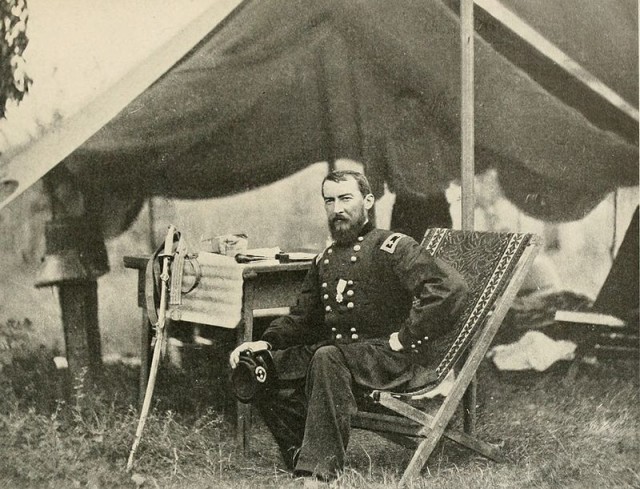

As the Union army around him gave ground, his men held their position and returned fire rapidly at the advancing enemy. Again and again, the Confederate soldiers assaulted his position with blade and bullet, but each time they found the defense could not be broken. Sheridan and his men fought with the bravery and determination of those who know that to retreat is to fail utterly.

As the morning wore on Bragg’s army’s efforts became concentrated on Sheridan and his fierce resistance at the center of the Union right. Bullets scarred the trunks of the Cedar trees, and the ground below them was red with blood. The Confederate dead were piled up at every point where the assault had been hottest, but still, Sheridan did not give up his position.

As the Confederate attack on Sheridan intensified, the attack on the rest of the Union right waned, and the reinforcements, chivvied on by Rosecrans himself, were able to reach their goal and strengthen the position held by those troops who had been forced back in the initial assault.

A little after 11 am Sheridan’s ammunition was running out, and he had no choice but to give the order to withdraw. He left more than a third of his men dead among the Cedar trees, but his actions had allowed the reinforcements to arrive, and when he reached the main body of the army he found an enormous mass of men and artillery assembled with their backs to the road.

The Confederate troops were now advancing into the teeth of massed volleys of cannon fire, and the regrouped Union forces were able to hold their position against the enemy advance.

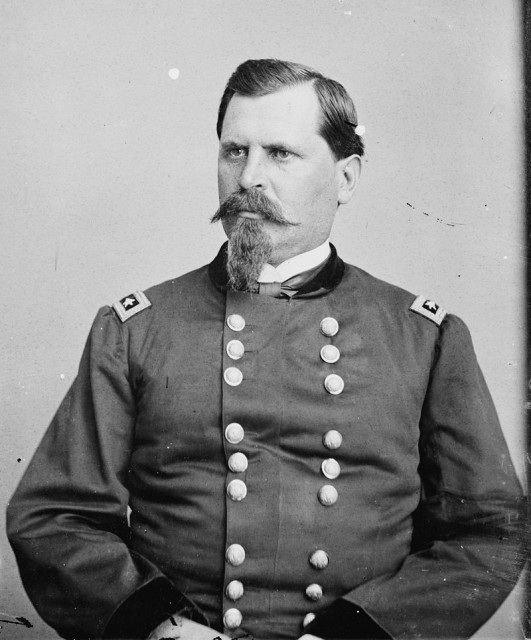

On the left flank of Rosecrans’ army, a similar story was taking place. William Hazen, a tough, battle-hardened veteran, held the center of his line steady while the rest of the army around him was driven back. Behind him, supporting fire from an artillery division helped his cause, but it was the hand to hand combat which saved the day for the Union army.

Again and again, Confederate assaults were repulsed, and it slowly became apparent to the attackers that Hazen’s brigade would fight to the last man. Without this resolute defense, the battle on the Union right would have been outflanked by Bragg’s troops, and all would have been over.

Instead, as late afternoon bled into the evening, the Confederate forces withdrew. Both sides had suffered horrific casualties, numbering many thousands, but the Union troops now held a strong position from which it would be hard to shake them.

The next day was New Years, January 1, 1863, and all was relatively quiet. After the horror and ferocious fighting of the previous day, both armies tended to the wounded and gathered up their dead. Great long wagon trains carried the unfortunate souls away north from the Union line, protected by units of cavalry.

The movement of troops was so significant that Bragg’s scouts reported to him, mistakenly, that Rosecrans’ army was retreating, so Bragg did not attack again. He thought he had gained a victory, but by the late afternoon of the next day he was aware of his mistake and ordered the assault to begin again.

The Union troops had regrouped and redeployed. The main strength of their artillery had been arrayed facing the approach to the river, while a considerable body of infantry had crossed it and now occupied a hill on the other side.

The Confederate attack was hard and determined, and the Union troops were forced back across the ford, but the Confederate forces found themselves advancing straight toward forty-five field guns, which laid down a relentless curtain of shot among them. After only an hour they had lost almost two thousand men, and they withdrew as they saw groups of Union infantry and Cavalry massing for the counter-attack.

Devastated, Bragg’s army began their retreat on January 3, and Rosecrans did not pursue him. He crossed the river and occupied Murfreesboro, where he started the long process of resting and rebuilding his army, and of reinforcing the town.

The American Civil war raged on for more than a year, and many more battles were fought. Few, however, were as costly as the battle at Stones River that New Year. More than twenty-four thousand men died there over a three-day period, in one of the bloodiest fights in that long and violent time in American history.

-by Barney Higgins