It goes by several names, but there’s no denying the absolute horror that took place in this small location in Georgia. Andersonville and the Andersonville National Historic Site also went by the names Camp Sumter and Andersonville Prison.

It was a horrific Confederate prisoner of war camp during the last months of the American Civil War. There were 45,000 Union prisoners held at the camp while it was open; almost 13,000 never made it out.

First Impressions

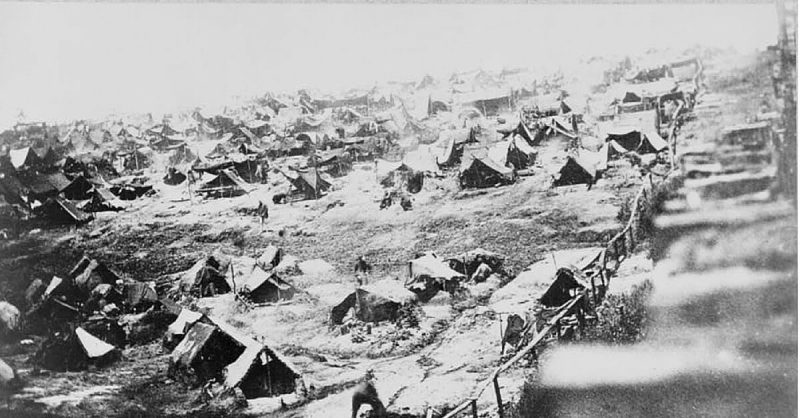

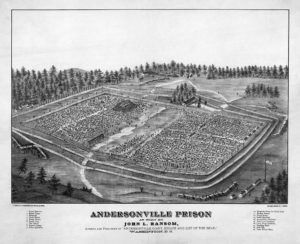

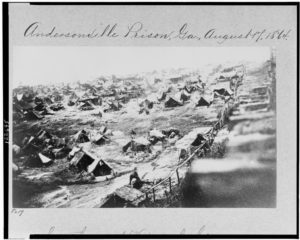

The prison opened in the early months of 1864. At first, it was on an about 17-acre plot of land, surrounded by 15-foot-tall barriers. After several months, the prison was enlarged to almost 27 acres. In the center was a few acres of swamp, and the marsh was used by prisoners as a toilet.

However, the rising fumes off the marsh were suspected to spread diseases from the human waste left there. Almost immediately the prison began to develop a reputation for its grotesque mistreatment. Eyewitness accounts say that those held there for even a short time were “mere walking skeletons, covered with filth and vermin.” Some described it as hell on earth.

Around the entirety of the camp, there was a lightweight fence that nearly any prisoner could have climbed over, about 19 feet away from the actual fence that kept prisoners inside. However, this 19 feet of empty space was called the “dead line,” and any prisoner who climbed over the smaller fence to get to the larger was shot dead on sight, no questions asked. It was an effective way of keeping prisoners from escaping.

Any who did escape were typically easily recaptured. The Union had reports of 32 escapees from Andersonville, while the Confederacy had reports of 351 escapees, including those who were recaptured, meaning a very small number actually succeeded in their efforts. However, some escapees that were not recaptured and that did not make it back to the Union forces, either died on their journey or quietly reentered civilian life without notifying the government.

It’s well known that the Confederacy suffered from a lack of funds during the war, so when the rebel forces had difficulty feeding their own soldiers, it’s no surprise that they allowed their prisoners of war to starve. The guards at the prison camp received small rations, but the prisoners received hardly anything, causing widespread emaciation and scurvy.

Scurvy and diarrhea were actually the two main causes of death within the camp (along with hookworm disease), with the latter being caused by the bacteria spread from the marsh mentioned above, and the necessity to drink from the same bodies of water where men were relieving themselves.

When food was given to the prisoners, it was oftentimes not pre-prepared, and the prisoners had no real way to cook the food. Though there was wood in abundance, they were not allowed to build fires, and were not given any utensils or cookware. As one would assume, this made cooking anything edible with the foodstuffs they were given, such as flour, nearly impossible.

Trouble From Within

If it weren’t quite enough that the prisoners had to deal with all this, there were also inner-prison gangs of sorts that were a constant threat as well. There was one group in particular called the Andersonville Raiders, who would plan attacks against their fellow prisoners.

They would then steal whatever it was that they wanted, from personal items to clothing to whatever meager food was available. They would use clubs and brute force in these attacks.

In response to this gang, another was created, calling themselves the Regulators. They offered a kind of vigilante justice, and worked to catch the Raiders before they struck. Then, they would put the Raiders on trial in a makeshift courtroom, with one Regulator acting as judge and the jury made up of random and unbiased prisoners pulled from whatever group of new soldiers had just arrived.

The Regulators would set their own punishments, which were by no means gentle. They gave many sentences of the stocks or the ball and chain, and even sentenced a handful to death by hanging.

Requested Release

Even the Confederacy realized at one point that the prison was far too overcrowded. The head, Captain Wirz, sent five of the prisoners to Union forces, asking for a prisoner exchange. However, the request was denied. Bravely, the Union soldiers who had been sent to ask for the exchange, returned to imprisonment.

Regardless, the Confederacy still wouldn’t give up on this notion. So, in the latter half of 1864, they told the Union that they would release some of the prisoners, if the Union would just send some ships to come get them. The Confederacy even sent some of the latest prisoners who were in good condition to port towns, where they could be retrieved.

However, once General Sherman started marching through Georgia, the prisoners were returned to Andersonville.

Notable Prisoners

Two notable prisoners at Andersonville were Dorence Atwater and Newell Burch. Atwater was a young man charged with the task of recording the deaths that occurred at the prison. He had something else up his sleeve, though. He started making his own list among the papers, and, when released, the list was published by the New York Tribune, as Atwater wanted to prove that the Confederacy was trying to ensure that Union prisoners would at least be unable to fight if they actually survived their stint in the camp.

He started making his own list among the papers, and, when released, the list was published by the New York Tribune, as Atwater wanted to prove that the Confederacy was trying to ensure that Union prisoners would at least be unable to fight if they actually survived their stint in the camp.

Burch was also a recorder of sorts, and he kept a diary of his time at the prison. He was the longest-held Union prisoner of the entire war, surviving 661 days and being transferred between several prisons.

After the War

After the end of the war, the prison was liberated. The head commander, Henry Wirz, received a military trial for war crimes. He was testified against by many former prisoners, though many did lie about his actions, as there were several conflicting stories that would have required Wirz to be in two places at once.

One of the most damning pieces of evidence, however, was a statement by a Confederate surgeon, who toured the camp and caught influenza and vomited twice while there. When stating his case, Wirz said that he had attempted to get more food for the prisoners, but he was sentenced to death by hanging.