This is the first in a series of posts, as guest blogger Justin Martin counts down to the September 17 anniversary of Antietam, still America’s bloodiest day. Martin’s posts will feature little-known episodes he learned about while researching his new book –

A Fierce Glory: Antietam—The Desperate Battle That Saved Lincoln and Doomed Slavery (Da Capo Press).

You can order the book here.

The Ragged Old First

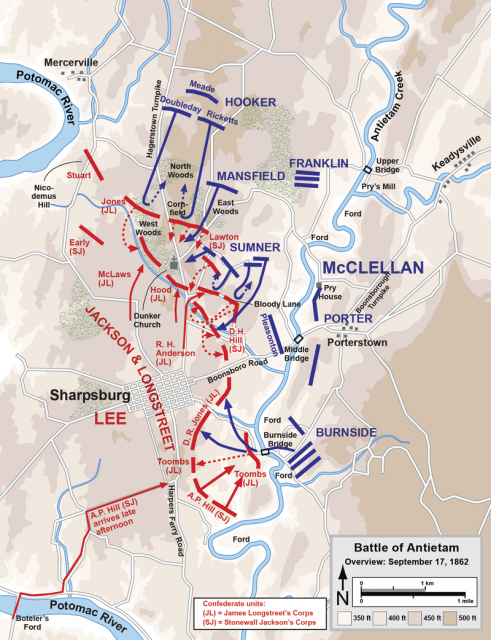

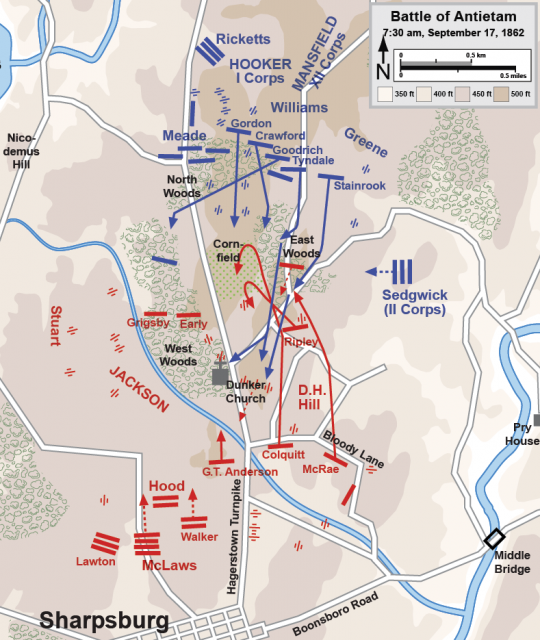

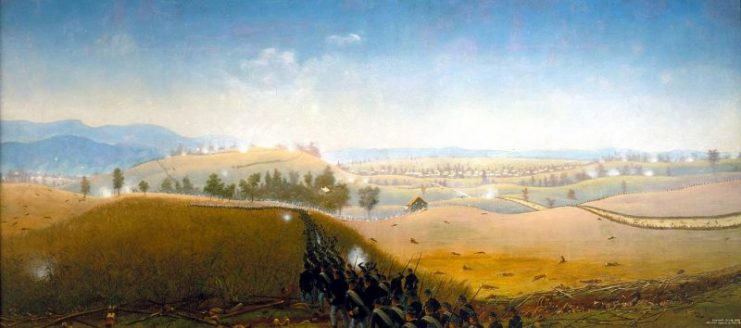

The 1st Texas was distinguished as one of only three Lone Star regiments that fought in the Eastern Theater during the Civil War. At Antietam, they saw action during the morning, participating in an epic tussle over Farmer David Miller’s 30-acre cornfield. In a pattern that was repeated over and over, Union soldiers advanced through the tall stalks only to be pressed back by the Confederates, neither side able to seize the advantage. The cornfield proved one of the battle’s most dangerous sites, marked by men falling dead or wounded at a rate of nearly one per second.

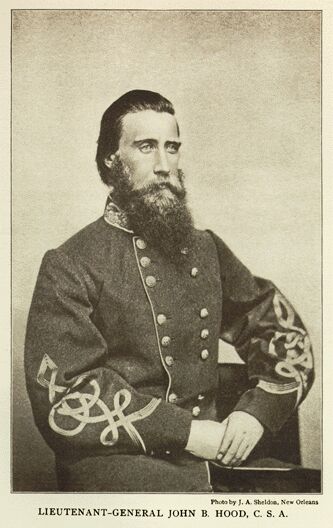

The 1st Texas was still eating breakfast when they were summoned into the fight. Along with their fellow Lone Star regiments, the 4th and 5th Texas, they were part of a massive wave of 2,300 fresh soldiers pressed into cornfield duty by Brigadier General John Bell Hood.

These men entered the fight enraged at the interrupted breakfast, many of them still stuffing hoecakes into their mouths as they formed into battle lines.

“The Ragged Old First,” as the regiment was known, proved particularly bold in their pursuit of the enemy. They lit off into the cornfield, making unnervingly rapid progress, staying hot on the brogan heels of the retreating Federals. They were supposed to remain in line with several other regiments.

Getting the Blood Up

Perhaps it was exuberance, or maybe simple bloodlust, but soon the Texans had pulled way out ahead. Among the many downsides of so-called linear tactics is the need for masses of men to move in tandem. A regiment that breaks off on its own and progresses too rapidly can find itself dangerously isolated. The 1st Texas was soon 150 yards in the lead. General Hood would later comment that they had “slipped the bridle and got away from the command.”

Just beyond the northern edge of the cornfield, Union soldiers waited. While the Confederacy had just loosed an angry breakfast-deprived hoard, the Union also had reserves, plenty of them, to draw upon. These fresh troops, Pennsylvania men, formed into a fearsome battle line; arranged west to east were the state’s 9th, 11th, 12th, 7th, 4th, and 8th regiments. Many of them knelt behind a low stone wall built by Farmer Miller.

The field hung thick with gun smoke; visibility was fast diminishing. So the Pennsylvanians were instructed to wait until they could see Rebel legs beneath the smoke. Then, direct fire above those legs.

The Cornfield Onslaught

The 1st Texas reached that northern edge of the cornfield—alone. There was an eerie calm as they continued forward and then, the deluge. They were hit with virtually everything available in a Civil War arsenal: rifled bullets and smoothbore balls as well as cannon shells lobbed over the Union battle line.

Some of the Pennsylvanians even fired buck and ball, a diabolical combination where a single musket load contains a ball and three pieces of buckshot, each about the size of a bb. The buckshot was capable only of limited damage. The idea was to fill the air with tiny stinging projectiles, a swarm of leaden gnats, overwhelming the enemy.

Soon enough the ball, the deadly component of mixture, was sure to find its mark. A soldier with the 4th Texas, which was trailing behind the 1st Texas, described the onslaught as “the hottest place I ever saw on this earth or want to see hereafter.”

The 1st Texas couldn’t retreat fast enough. Now it was the Union soldiers in pursuit. But the counterattack soon fizzled, as so many had throughout the day.

Back at the southern end of the cornfield, the 1st Texas, which had first entered these rows with bold swagger, exited in a tattered trickle. The “Ragged Old First” nickname was now painfully fitting. Of the 226 that had gone into battle, 45 had been killed, 141 wounded. That’s an 82 percent casualty rate, and would stand as the worst toll for any regiment, Confederate or Union, during a Civil War battle.

Losing the Colors

The 1st Texas suffered other losses, too, though these were more in the realm of pride and honor. While he accounted for survivors, Captain John Woodward was suddenly seized by panic. “The flags, the flags! Where are the flags?” he cried.

During the retreat, it seems, some Pennsylvanians had managed to overtake the 1st Texas color guard. A desperate fight ensued: standard-bearer after standard-bearer went down, but someone always stepped forward to maintain possession of the flags.

Corporal William Pritchard was the last Texan known to hold the colors. Surrounded by Yanks, he was sprayed in the face with buckshot. As he brought up his hands for protection, a ball lodged in his gut. The wounded corporal looked on helplessly as men from the 9th Pennsylvania dashed off with the captured flags. In the spot where this melee took place, legend has it that the bodies of ten Texans were later found, each having tried valiantly but unsuccessfully to protect the colors.

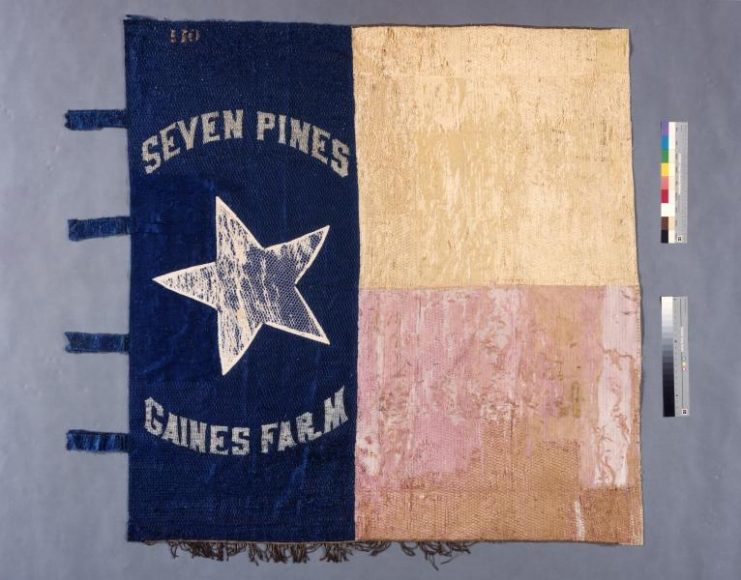

The loss of the Confederate battle flag, featuring the familiar St. Andrew’s Cross, brought shame and sorrow enough to the Texans. But they had also surrendered their regimental flag. This was a Texas state flag, hand-sewn by Charlotte Wigfall, the wife of their first commander, the man that had originally mustered them into service.

Painted onto the flag were the names of battles in which the regiment had fought: Seven Pines, Malvern Hill, and Eltham’s Landing. Even the flag’s lone white star had a story, for Mrs. Wigfall had lovingly cut it from her own wedding dress.

Read another story from us – Stonewall Jackson’s Early Masterpiece – The Shenandoah Valley

For the 1st Texas, their day was over, their Antietam fight, ended. The survivors made for safety of the woods, lay down, and let the remorse wash over them.