Battles don’t unfold as one might imagine. They don’t progress in orderly or predictable ways. Smack in the middle of the bloodiest day in U.S. history, a curious calm settled over the field. Among the soldiers who fought at Antietam, this two-hour would come to be known as the “lull.”

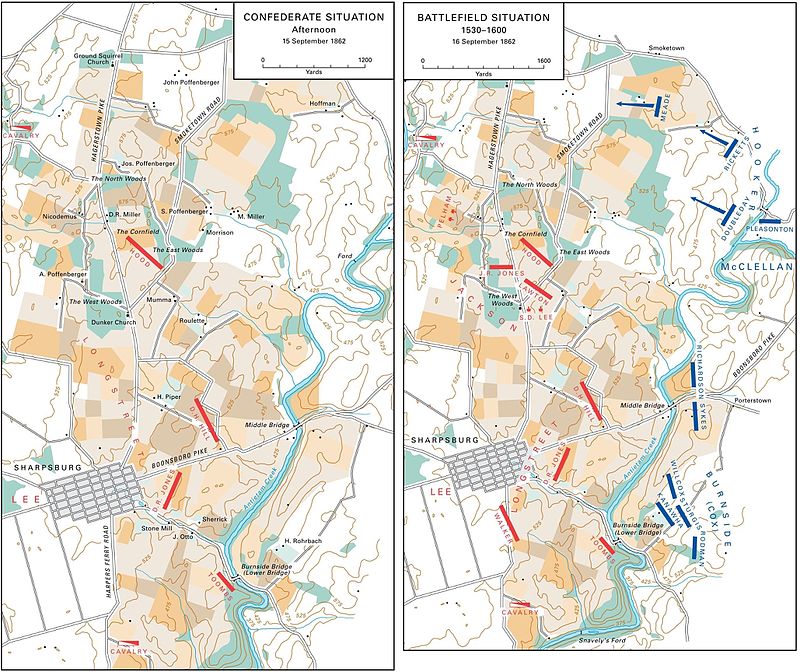

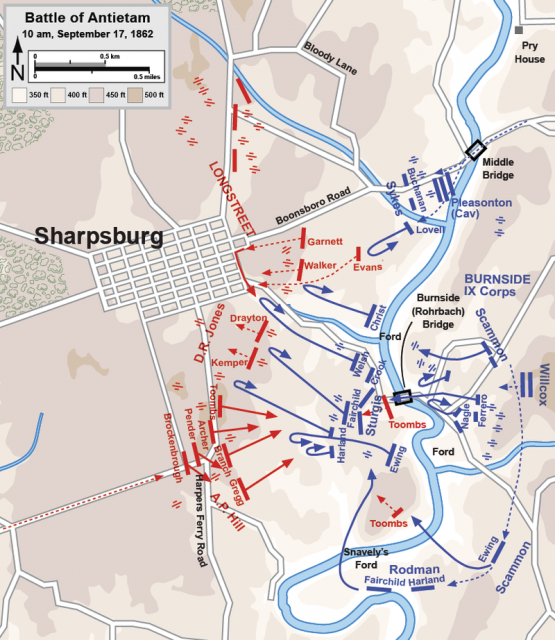

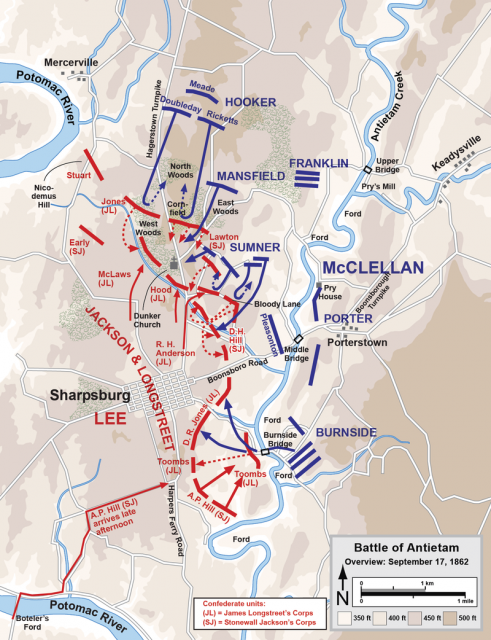

Beginning at daybreak, there had been seven hours of continual, unremitting bloodshed. At 1 PM, a large Federal force commanded by Ambrose Burnside finally managed to fight its way across Antietam Creek. This breakthrough occurred on the southernmost portion of the battlefield.

The Union was now poised to mount a final assault, possibly crush the Confederate army. But hold on, it wasn’t so simple. To launch that assault, dozens of regiments needed to be positioned along a massive, mile-wide line; caissons filled with ammo had to moved nearby; cannon had to be hauled to the choicest spots.

While this vast logistical undertaking was underway, nearly every other soldier elsewhere on the battlefield, both Yank and Reb, took a needed break. Certain places (The Cornfield, West Woods, and Bloody Lane), sites of the morning’s ferocious clashes, fell nearly still. Musket and cannon fire—which had maintained an unearthly din—dwindled to a few stray pops. It was almost as if the two sides had jointly agreed to a siesta. In truth, this break in the action was organic, spontaneous, borne of exhaustion.

During the lull, soldiers seized the opportunity to eat a meal. It was lunchtime, after all. Bayonets—disturbing to use on a man, even one’s sworn enemy—proved ideal for skewering farmers’ chickens, and cooking them over open fires. Soldiers read newspapers and the Bible, or wrote letters home. They swapped stories, told jokes. Out came the little portable chess sets. Some men had sewed checkered patterns onto their bedrolls, creating readymade chessboards.

The soldiers engaged in chuck-a-luck, a gambling game that employs three dice, or brag, a card game similar to poker. Those that could, napped. The regiment historian for the 35th Massachusetts recalled that “some of our men dozed.”

Many soldiers, Yank and Reb, made coffee. Others opted for a different mild stimulant, breaking out their tobacco. They smoked cigars and pipes, popped fat plugs in their mouths to chew or took pinches of “snouse,” which consisted of finely minced leaves cut with herbs.

Sensing the quiet, a pig and her litter burst from the woods and went darting among the men of the 9th New Hampshire. The big sow ran between the legs of one soldier, lifting the shocked man off the ground and carrying him backwards a ways. His comrades roared with laughter.

In other places, there was nothing but pain and grief. Wounded soldiers lay on the ground near dressing stations that were too overwhelmed by the morning’s mayhem to provide aid to everyone that needed it. Thousands of prisoners waited behind enemy lines, consumed with uncertainty.

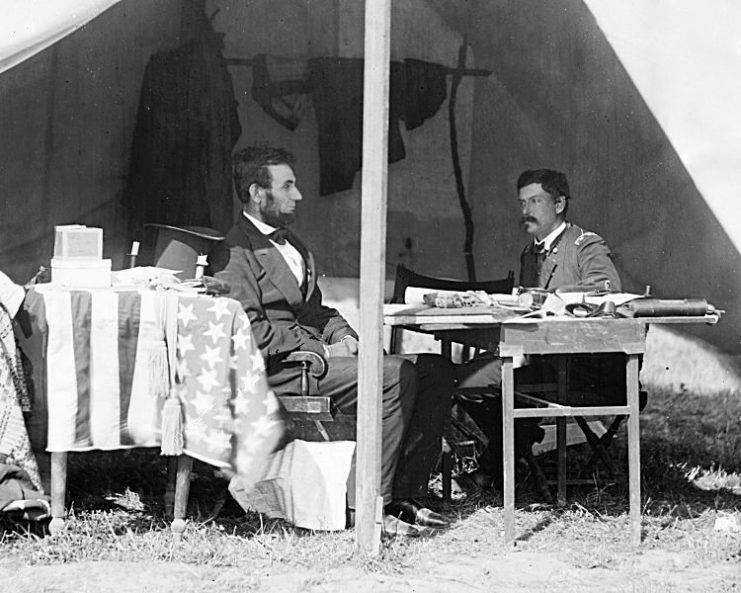

The two rival commanders were busy during the lull. The Union’s George McClellan took the opportunity to write a couple telegrams. One was addressed to Henry Halleck, general-in-chief of the Union army, back in Washington. McClellan knew it would be routed to Lincoln. So he composed with care, writing but then striking through a line hinting that “great defeat” was possible. No doubt, he worried that this would raise the specter of possible failure. But then another line he tried seemed perhaps too presumptuous of success; he crossed it out, too.

After picking over his words, McClellan settled on a brief message, fittingly dramatic, suitably vague, and including the following: “We are in the midst of the most terrible battle of the war, perhaps of history—thus far it looks well but I have great odds against me.”

During the lull, for the first time all day, McClellan also visited the actual battlefield, making a suitably dramatic entrance. He arrived in the saddle of a large bay horse named Daniel Webster. Near the Bloody Lane, McClellan conferred with two of his corps commanders, William Franklin and Edwin Sumner. They discussed the wisdom of launching a second surprise attack on the Rebel center even as the Union final assault was being organized on the southernmost portion of the field.

With the enemy in torpor, now was the time. But what if the sneak attack failed, simply resulting in a smaller force available for later in the battle when more men might be needed? What if Lee seized the opportunity to counterattack, striking some unexpected and vulnerable place along the Federal front?

Ever-cautious McClellan decided to hold off, maintaining the focus on that planned final assault in the southernmost portion of the battlefield.

While McClellan sputtered, Lee schemed. The Rebel commander was busily planning a counterattack, exactly as the Federals feared. What he had in mind was trademark bold: the Rebels would slip around the Union soldiers massed at the northernmost part of the field. That would make it possible to attack from a shocking and unexpected direction. The Rebels could strike from the rear.

An order went out for available cannon to be consolidated for the effort. Among the Rebel batteries that answered the call was one now reduced to horses and ammo enough to operate a single gun.

Lee was standing near his horse Traveller when this particularly decrepit battery dragged past.

“General are you going to send us in again,” asked a young man, his face streaked black with powder.

At first, Lee stared through the youngster. But then the briefest flash of recognition crossed his face. Why, it was his own child! It was Robert Lee Jr.

“Yes, my son,” said Lee, “you all must do what you can to help drive these people back.”

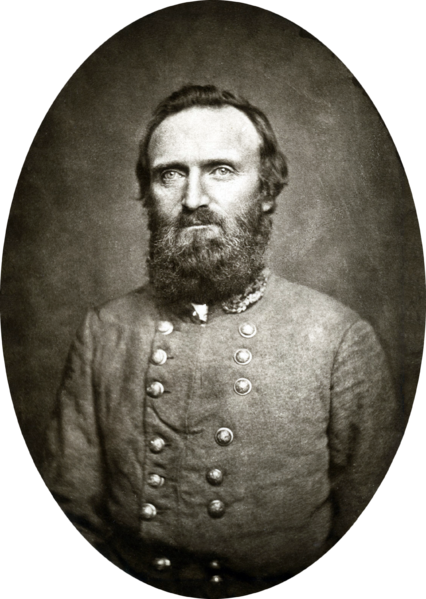

At this same time, Stonewall Jackson was rounding up soldiers for the counterattack. But it was also vital to get an idea of the size of the Federal concentration on the northernmost part of the battlefield. So he ordered a North Carolina private to shimmy up a tall hickory to do some reconnaissance. Jackson asked the soldier for an estimate of how many bluecoats they faced.

“Who-e-e! There are oceans of them, General,” replied the private.

“Count their flags,” demanded Jackson.

The private began to count out loud. When he reached 39, Jackson asked him to climb back down the hickory. Assuming two flags to a regiment, roughly a thousand soldiers per, the general’s natural estimate … well, they faced an ocean of Federals.

Lee also put his sneak attack on hold for now.

The lull also provided a boon for journalists. For many hours, the battle had limited their investigations. With the fighting temporarily cooled, they sallied forth, moving freely over the field. Charles Coffin of the Boston Journal took the opportunity to visit the Bloody Lane, where he surveyed the scene with his unflinching reporter’s eye. “[W]hat a ghastly spectacle,” he would write. “The Confederates had gone down as the grass falls before the scythe. They were lying in rows, like the ties of a railroad; in heaps, like cord-wood, mingled with the splintered and scattered fence rails.”

The New York Tribune, seeking an edge in the tough newspaper racket, had dispatched a team of four reporters. They spread out, covering different parts of the field. George Smalley, the team’s ace and a highly enterprising man, ranged broadly. Somehow he had managed to commandeer a horse as well as a Federal uniform, complete with sash and sword.

“Who are you?” he was repeatedly asked.

“Special correspondent of the New York Tribune, sir.”

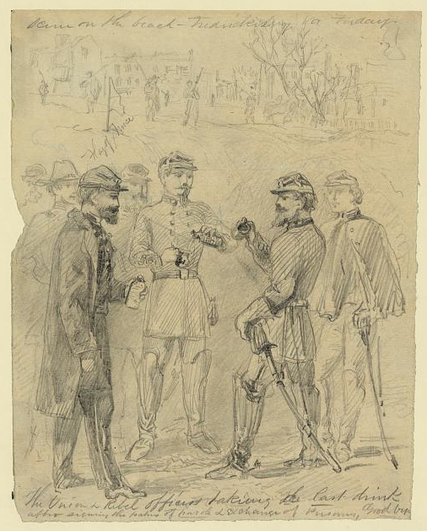

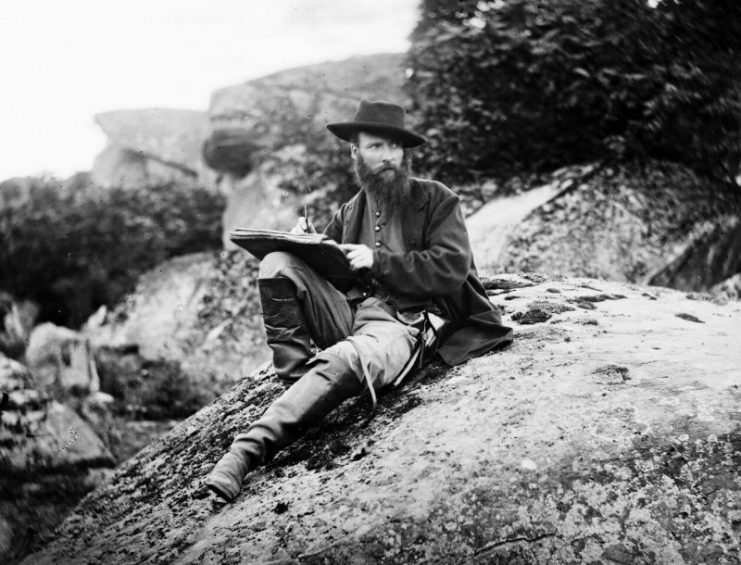

Also out in force were the “special artists.” This breed of journalist sketched the action in real-time, providing a unique window into warfare for the public. Among the established stars in the special-artist firmament were Alfred Waud of Harper’s Weekly and Frank Schell of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper. Both were present, pads and pencils out, furiously sketching.

During the break in the action, Schell visited Miller’s cornfield and surveyed the horrors. Walking among the broken stalks, he was alarmed to see a kneeling Confederate pointing a musket at him.

“I jumped aside,” Schell would recall, “but his aim did not follow.”

Turns out, the Rebel was dead, frozen in “mute fidelity,” as the artist put it, to the final pose he’d struck upon this earth.

So to recap: here’s what the action consisted of over two midday hours during the battle of Antietam. Federal regiments were shuffled into place, preparing for a final assault. Elsewhere, soldiers read and relaxed, smoked and gambled. McClellan and Lee strategized. Journalists ranged about the field, reporting on the earlier carnage.

And then, come 3PM—break over! That mile-long Federal line began to roll forward; the final assault was underway. Soon the air was filled with the pop pop pop of muskets, the roar of cannon, the screams of men, and the whinnies of frightened horses, not to fall silent again until the terrible day ended.

This is one in a series of posts, as guest blogger Justin Martin counts down to the September 17 anniversary of Antietam, still America’s bloodiest day. Martin’s posts will feature little-known episodes he learned about while researching his new book, A Fierce Glory: Antietam—The Desperate Battle That Saved Lincoln and Doomed Slavery (Da Capo Press).

You can order the book here.

Justin Martin will continue to share some special and insightful stories about the Battle of Antietam throughout the week. Please stop by tomorrow to catch the next installment.