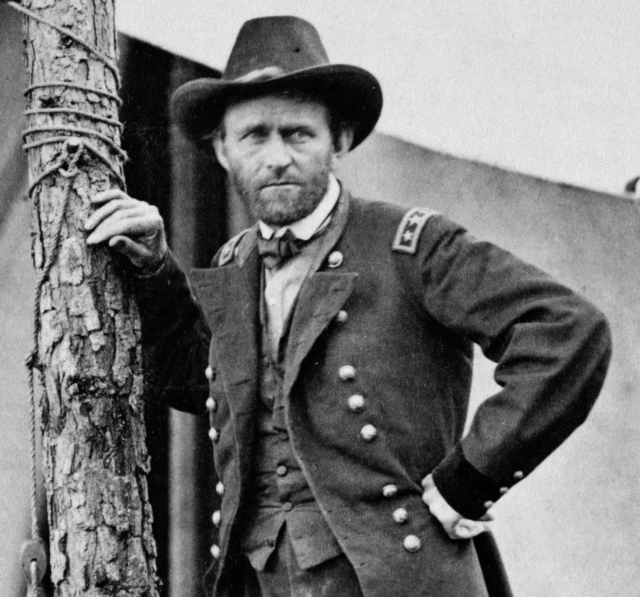

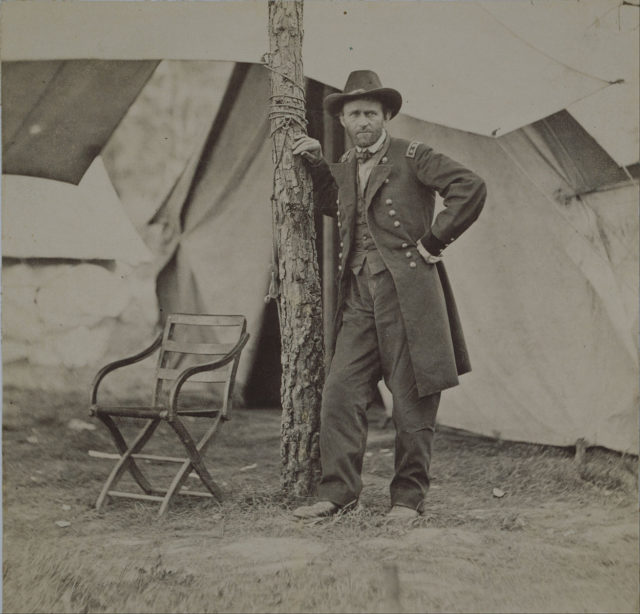

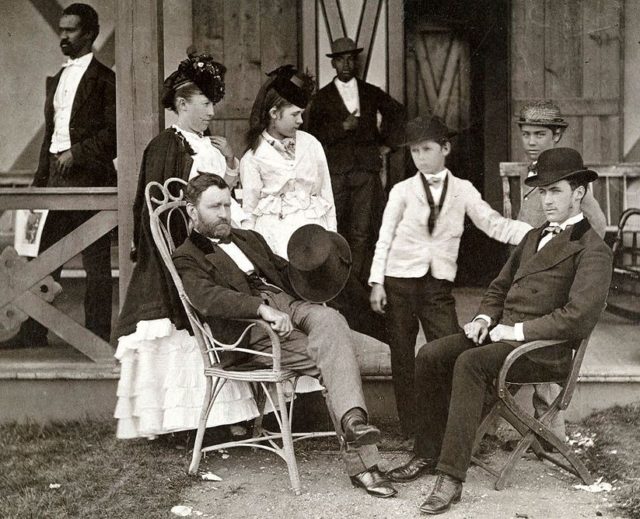

General Ulysses S. Grant transformed the way the American Civil War was fought. By shifting to a strategy of “baseless” campaigning he freed himself from supply lines, increasing his ability to maneuver. He devastated the lands he went through, embittering the Confederates against him.

Historically, it was not a new strategy. In the context of the American Civil War, it was revolutionary.

A Restrained War

Many wars have seen armies live off the land. It was not uncommon for the strategy to be taken to extremes, deliberately destroying what was not consumed, either for profit or to break enemy morale. From the English chevauchee raids of the Hundred Years War to Napoleon’s foraging in Spain, there were many precedents.

The American Civil War started differently. It was a war that began with restraint.

The Confederate President Jefferson Davis said, “all we ask is to be let alone.” Union President Abraham Lincoln believed he was putting down a domestic insurrection. By limiting the impact of the war, he thought it would be easier to reunite a divided nation. He wished to avoid feuds and bitterness from which the states might never recover.

Despite the bitter and destructive raiding of some local conflicts, the Union armies minimized their disruption. They relied on supplies sent to them rather than living off the land.

Early Campaigns: The River System

For Ulysses S. Grant, raised in the basin of the Mississippi River, the way to deal with supplies was obvious. He transported them by water.

For the first year and more of the war, that is what he did. The water courses that had spread trade and settlements west became the arteries of his army. Water transport was less burdensome and expensive than carrying supplies overland. It did not rely on the rail networks to keep goods moving.

The downside was that it restricted Grant’s operations geographically. He had to stay within reach of the rivers if he wanted to keep his armies supplied with food and ammunition.

Failing to Break Out

The other drawback was that the Confederates used those limitations against him. They held onto choke points on the river network, places like Fort Henry, Port Hudson, and Vicksburg.

It severely limited Grant’s ability to advance. He could not work his way down the main water courses, going with the flow of the river. Instead, he had to slow down to explore backwaters, looking for routes to enable him to advance while maintaining supplies.

He was eventually driven to the extreme measure of digging a canal across a bend of the Mississippi River, hoping to bypass Vicksburg. None of it enabled him to break out of the restrictions of the river system. His own supply lines were strangling Grant.

Experiments in Foraging

In November 1862, Grant decided to try a different approach. If he was going to make the advances he wanted, he needed to change his approach to supplies. He went foraging.

The respect for southern property that had held him back for so long was not abandoned. He began with a relatively small experiment. The extent of the foraging and what it was meant to achieve was limited. It was a chance to see if the material benefits would outweigh the political cost.

The results exceeded all expectations. No-one before had taken such an approach in the richly productive areas of the Confederate States. Grant was amazed. He wrote, “we could have subsisted off the country for two months instead of two weeks without going beyond the limits designated.”

Baseless Campaigning

The following May, Grant threw caution to the wind and embraced a foraging strategy. By feeding his army on local produce, he avoided the need to maintain transport links to home. He no longer needed to base himself around a river network.

Baseless campaigning had arrived.

A further reason was added by the state of the war. 1862 had seen Confederate counter-attacks and close calls in battles for the Union. Grant himself had nearly been beaten at the Battle of Shiloh. Faced with the possibility of defeat, the gloves came off.

From the start, some parts of the western theater had seen bitter and destructive fighting. Faced with raids by rebel sympathizers, local commanders had tried to attack their supply base.

Grant embraced that method as part of his baseless campaigning. At the siege of Vicksburg, he set out what would become his standard approach. Every scrap of food in the surrounding area that could be taken was taken. The rest was burnt.

He was punishing the South for its rebellion. He was adding an extra strain to its infrastructure, as civilians fled devastated areas in search of food and shelter. He was enabling his army to become more mobile.

Reactions and Doubts

Many expressed doubts at what Grant was doing. In May 1863, General Sherman warned Grant they were weakening themselves through baseless campaigning. He argued that any great army should make sure it had a source of supplies. He was drawing upon the work of Antoine-Henri Jomini, an influential military theorist whose work was based on Napoleon.

Grant was unmoved and stuck to his course of action. Sherman changed his tune when he saw the results. He became the most famous forager and looter to invade the Confederacy.

Punishing the Enemy, Feeding his Men

Having shaken off his restraints, Grant embraced the devastation that he could bring. Railroads were ripped up and the sleepers warped beyond use. Farms were raided and then destroyed. For miles around his advance, families were driven from their homes, becoming a burden on the ever more strained Confederacy.

Baseless campaigning made the war faster and more mobile. It also made it more destructive and embittering.

Grant had transformed the American Civil War.

Source:

John Keegan (1987), The Mask of Command;