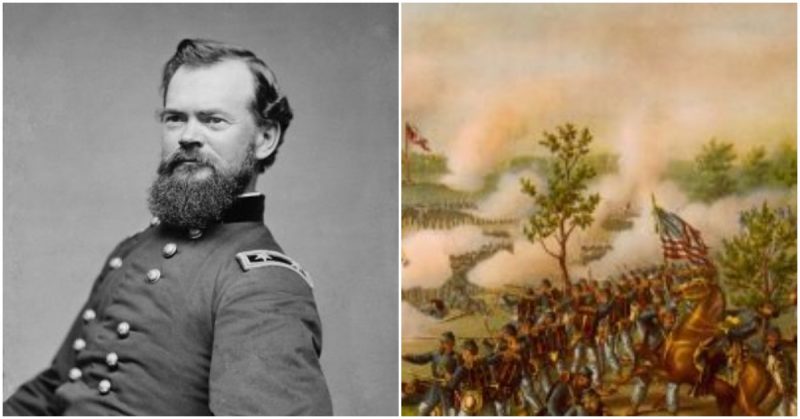

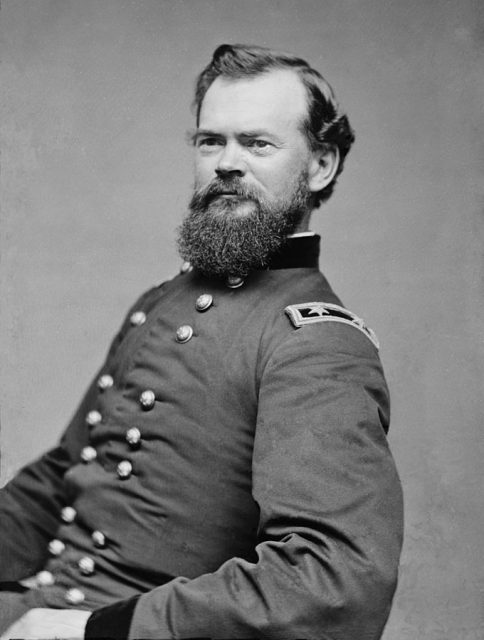

James Birdseye McPherson began his career after graduating first in his class from the United States Military College in 1853, a class that included Philip Sheridan and future enemy John Bell Hood.

After graduation, he was assigned to the Army Corps of Engineers and participated in building improvements in New York, the building of Fort Delaware, and the strengthening on works on Alcatraz Island in San Francisco Bay.

In 1860, Abraham Lincoln was elected president and the beginning of the secession crisis was becoming evident. Spurred by this, McPherson chose to fight for the Union.

As the Civil War began in April 1861, he realized that his career would be best served if he returned east. Asking for a move, he received orders to report to Boston for service in the Corps of Engineers as a captain. Though an improvement, McPherson wanted to serve with one of the Union armies then forming.

Upon his arrival, he was promoted to lieutenant colonel and assigned as chief engineer on the staff of Brigadier General Ulysses S. Grant. Impressed with the young officer, Grant had him promoted to brigadier general in May.

That fall saw McPherson in command of an infantry division during the campaign around Corinth and Iuka, Mississippi. Again performing well, he received a promotion to major general on October 8, 1862. His great run in the Union Army, however, came to an abrupt end in the furious Battle of Atlanta.

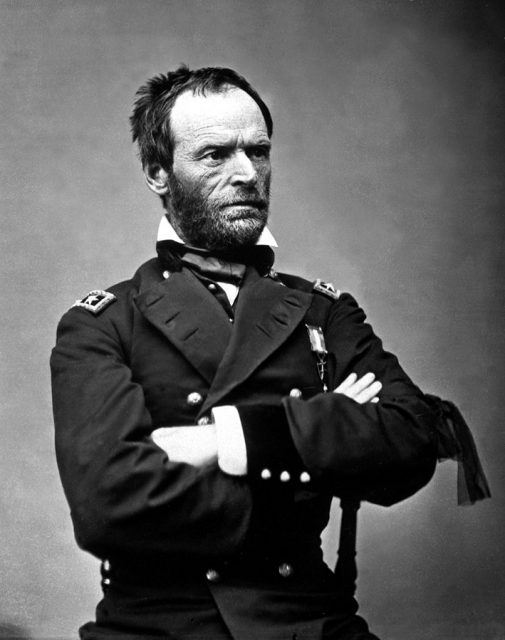

It was July 21, 1864; Gen. William T. Sherman’s three armies were more or less separated. Better yet, Confederate Maj. Gen. Joseph Wheeler reported that as Gen. James B. McPherson’s army marched in on Atlanta from the east, it had its left side “in the air” (Sherman had sent Kenner Garrard’s cavalry east to wreck the Georgia Railroad).

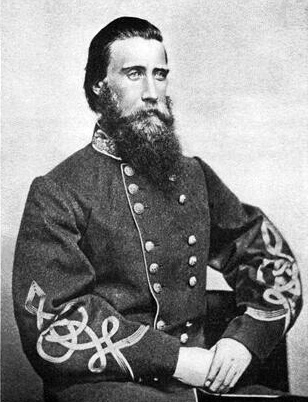

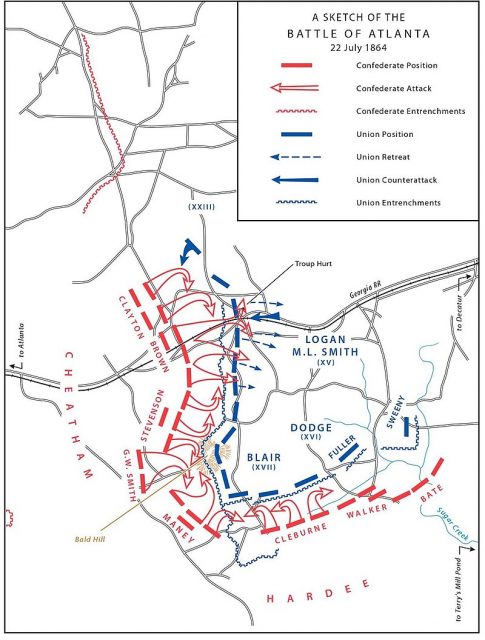

This situation presented Gen. John Bell Hood with an opportunity to surround his enemy much like Jackson did at Chancellorsville. Hood planned for his forces to drop back from their outer lines north of the city into the main strengthened outside border around the city on the night of July 21-22. Gen. Alexander P. Stewart and Maj. Gen. Benjamin Cheatham would hold the works.

Lt. Gen. William Hardee’s corps would march through and out of the city, southeast then northeast toward Decatur, guided by Wheeler’s cavalry, and jump into McPherson’s left-rear while Wheeler attacked McPherson’s wagon trains.

It was an exciting plan, calling for a 15-mile night march by Hardee’s troops and a dawn attack on the 22nd. But a late start, fatigue, a hot night, dusty roads, and poor service from the cavalry combined to bring the four attack-related divisions not close enough to McPherson’s rear.

Then rough land added further delay and Confederate Maj. Gen. W.H.T. Walker was shot and killed getting his division into place. Hardee’s “surprise” attack did not begin till shortly after noon.

The Union forces were blessed with a lot of good luck that day. By chance, a Union division under Brig. Gen. Thomas W. Sweeny happened to be in just the right position to meet Hardee’s opening attack. Instead of overrunning hospital tents and wagon trains in McPherson’s rear, Walker’s and Bate’s troops ran instead into a division of deployed enemy infantry.

General McPherson, having left Sherman’s headquarters at the Augustus Hurt House (now Carter Center) just before the firing started, was on this part of the field watching Sweeny deal with the attack. He then rode off to check on Frank Blair’s Seventeenth Corps, which by now had been struck by Maj. Gen. Patrick Cleburne’s hard-hitting division.

McPherson and his staff were riding down a wagon road when they unexpectedly ran into part of Cleburne’s line. “He came upon us suddenly,” remembered Capt. Richard Beard of the 5th Confederate:

“I threw up my sword as a signal for him to give up. He checked his horse, raised his hat in salute, wheeled to the right and ran off to the rear in a run. Corporal Coleman, standing near me, was ordered to fire, and it was his shot that brought General McPherson down.”

McPherson’s assistants dashed off. One Union officer struck a tree in his flight; the blow smashed his pocket watch and froze the time of the general’s death–2:02 p.m. Confederate Captain Beard came up to the body and saw a bullet hole in the back, near the heart.

He stayed only long enough to identify the fallen enemy officer as McPherson before continuing his advance. Later, one of McPherson’s staff officers led a squad back to the scene, retrieved the general’s dead body, and bore it to Sherman’s headquarters. Sherman was moved with sadness for his now dead friend. McPherson had started the war as a Captain and died as the 2nd highest ranking Union officer of the war killed in action.

Cleburne’s attack at first overran part of the Union line, confiscating two guns and taking more than two hundred prisoners. Then the Southerners ran up against the infantry and big guns on a hill occupied by Brig. Gen. Mortimer Leggett’s division, and were stopped. Maney’s Confederate division joined in the fight, but Leggett held onto his hill.

Around 3:00 p.m., Hood ordered Cheatham’s division to launch an attack from Atlanta’s eastern line of works. Cheatham’s attack against the Federal line held by John A. Logan’s Fifteenth Corps met with success at first, overrunning the Yankee line at the Troup Hurt House and capturing artillery until a Union counter-attack forced it back.

Cleburne’s and Maney’s divisions gave up their fight, too. At the end of the afternoon the Confederates retired to their initial positions. The Battle of Atlanta was over, save for the sporadic roar of a big gun and rifle fire into the night.

General Logan, named to replace McPherson for the moment, reported 3,722 killed, wounded, or missing in the Army of Tennessee. Hardee counted 3,299 dead in his corps, while Cheatham lost probably half that number.

Adding in more than two hundred deaths in Wheeler’s cavalry (from its unsuccessful attack on the Union wagon train at Decatur), Confederate losses on July 22 added up to about 5,500. Hood’s effort to roll up Sherman’s left side had failed.

A bronze statue of Major General James B. McPherson resides in McPherson Square in Washington D.C. The project was authorized by the United States Congress on March 3, 1875, and was installed on October 18, 1876, on the 11th annual reunion of the Army of Tennessee.