Merriment rang out in the streets of Washington on July 16, 1861 as Gen. Irvin McDowell’s army, 35,000 strong, marched out to begin the campaign to confiscate Richmond and end the war.

It was an army of green recruits, few of whom had the faintest idea of the severity of the job facing them. Their bold strides, however, emphasized the confidence that the army had concerning the war’s outcome.

As excitement spread, many people and congressmen with wine and picnic baskets followed the army into the field to watch what everyone expected to be a colorful show. The troops were 90-day volunteers called for by President Abraham Lincoln after the news of Fort Sumter exploded over the nation in April 1861.

The men, recruited from shops and farms, had little knowledge of what fighting a war would entail. The first day gained a disappointing five mile march mainly due to the lack of discipline among the soldiers, most of who were not accustomed to army protocol. They stole away regularly so as to pick berries or fill water containers along the way.

Whilst President Lincoln and the Union Army sought to bring a very quick end to the rebellion in the Manassas campaign, the rival Confederates had other plans. The battle was an opportunity for them to prove to the Union that they had the military resources and strategy to keep the war going. It was a simple case of winning the conflict by not losing.

The Mission was simple, “Stop the Federals from marching further towards Richmond at any cost.”

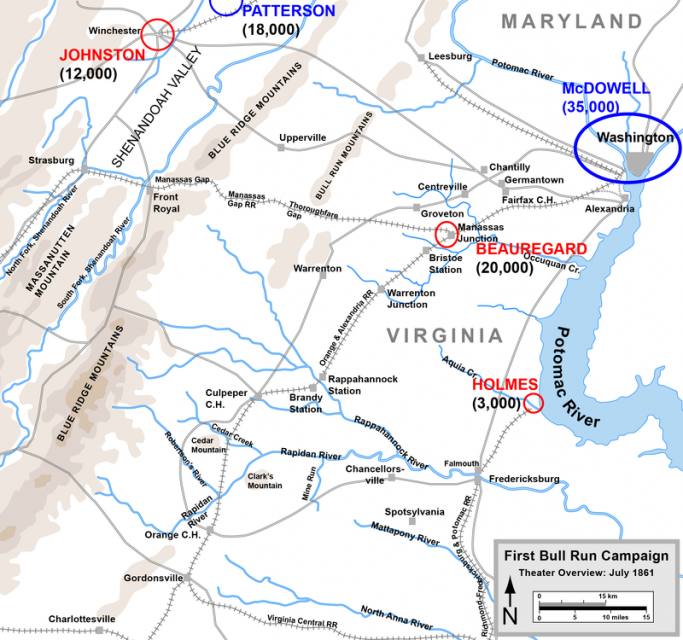

McDowell’s slowly-moving columns were headed for the very important railroad junction at Manassas. Here the Orange and Alexandria Railroad met the Manassas Gap Railroad, which led west to the Shenandoah Valley. If McDowell could grab and take control of this junction, he would stand on either side of the best overland approach to the Confederate capital.

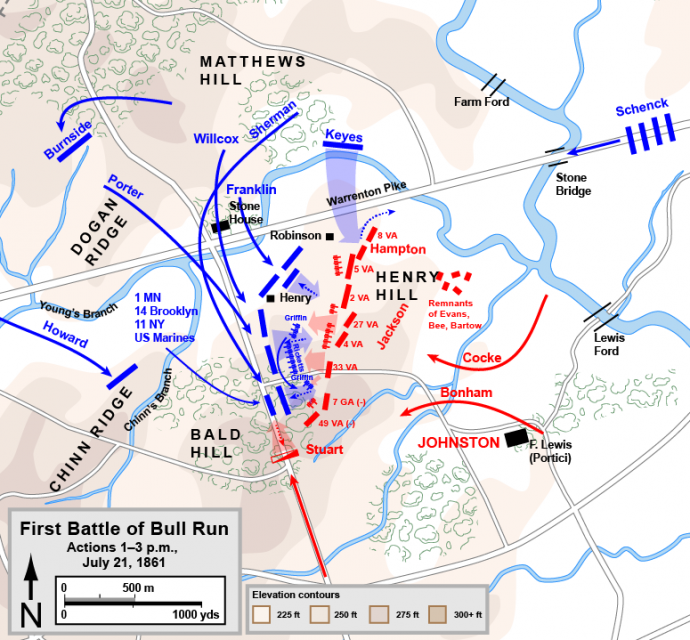

On July 18 McDowell’s army reached Centreville. Five miles ahead a small wandering stream named Bull Run crossed the route of the Union advance and there guarding the fords from Union Mills to the Stone Bridge were 22,000 Southern troops under the command of Gen. Pierre G.T. Beauregard.

McDowell first tried to move toward the Confederate right side, but his troops were checked at Blackburn’s Ford. He then spent the next two days scouting the Southern left side. In the meantime, Beauregard asked the Confederate government at Richmond for help. Gen. Joseph E. Johnston, assigned in the Shenandoah Valley with 10,000 Confederate troops, was ordered to support Beauregard if possible.

Johnston gave the opposing Union army the slip and, employing the Manassas Gap Railroad, started his military units toward Manassas Junction. Most of Johnston’s troops arrived at the junction on July 20 and 21, some marching directly into the fight.

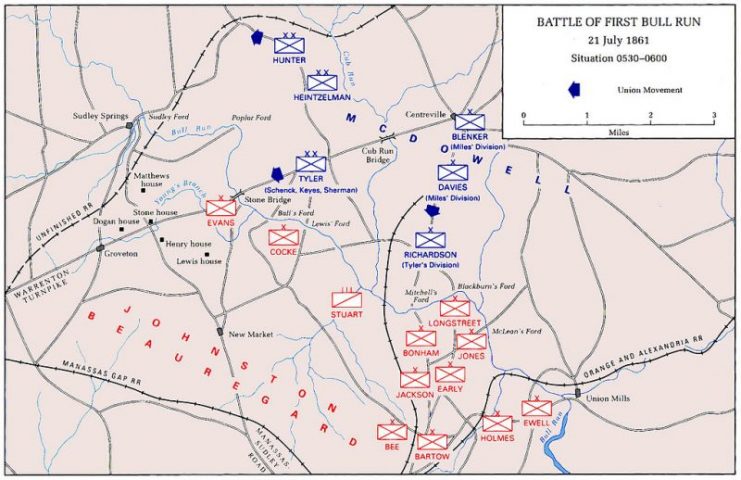

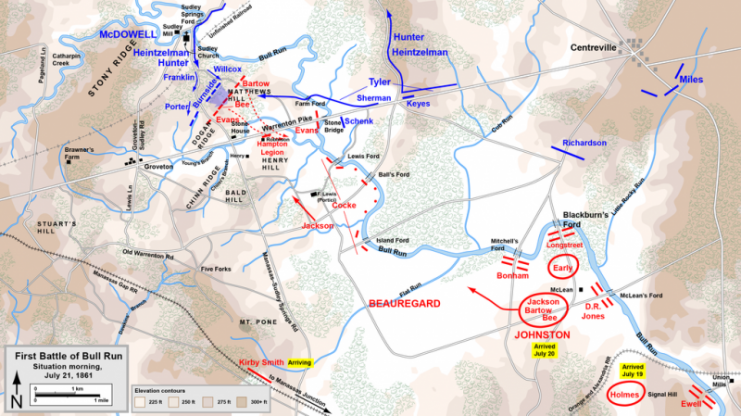

On the morning of July 21, McDowell sent his attack columns in a long march north towards Sudley Springs Ford. This route took the Federal army around the Confederate to the left. To distract the Southerners, McDowell ordered a diversionary attack where the Warrenton Toll highway crossed Bull Run at the Stone Bridge. At 5:30 am the deep-throated roar of a 30-pounder Parrott rifle shattered the morning calm, and signaled the start of the fight.

McDowell’s new plan depended on speed and surprise, both very hard with inexperienced troops. Valuable time was lost as the men tripped while walking through the darkness along narrow roads. Confederate Col. Nathan Evans, commanding at the Stone Bridge, soon understood that the attack on his front was only a diversion.

Leaving a small force to hold the bridge, Evans rushed the rest of his command to Matthews Hill in time to check McDowell’s lead unit. But Evans’ force was too small to hold back the Federal Army for long.

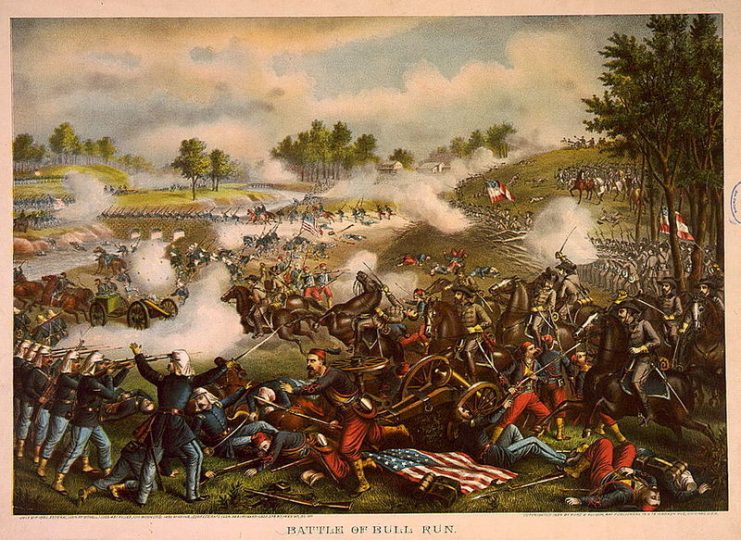

Soon military units under Barnard Bee and Francis Bartow marched to Evans’ help. But even with the reinforcements, the thin gray line collapsed and Southerners ran away toward Henry Hill. Trying to rally his men, Bee used Gen. Thomas J. Jackson’s newly arrived military unit as a source of support and security.

Pointing to Jackson, Bee shouted, “There stands Jackson like a stone wall! Rally behind the Virginians!” Generals Johnston and Beauregard then arrived on Henry Hill, where they helped in rallying shattered military units (or groups of people) and redeploying fresh units that were marching to the point of danger.

Around noon, the Federal Army stopped their advance to reorganize for a new attack. The inactive time lasted for about an hour, giving the Confederates enough time to reform their lines. Then the fighting resumed, each side trying to force the other off of Henry Hill.

The fight continued until just after 4 p.m., when fresh Southern units crashed into the Union right side on Chinn Ridge, causing McDowell’s tired and discouraged soldiers to withdraw.

At first, the retreat was well-organized. Screened by the regulars, the three-month volunteers retired across Bull Run, where they found the road to Washington jammed with the carriages of congressmen and others who had driven out to Centreville to watch the fight. Panic now grabbed and took control of many of the soldiers and the retreat became an embarrassing loss.

The Confederates, though helped by the arrival of President Jefferson Davis on the field just as the fight was ending, were too disorganized to follow up on their success. Daybreak on July 22 found the defeated Union army back behind the teeming defenses of Washington.

Even though there is the existence of their victory, Confederate troops were far too disorganized to press their advantage and chase after the backing away Yankees, who reached Washington by July 22. The First Fight of Bull Run (called First Manassas in the South) cost some 3,000 Union deaths, compared with 1,750 for the Confederates.

Its result sent northerners who had expected a quick, clear victory reeling, and gave joyfully celebrating southerners a false hope that they themselves could pull off a fast victory.

In fact, both sides would soon have to face the reality of a long, very difficult conflict that would take an impossible to imagine toll on the country and its people.

Read another story from us: Stonewall Jackson’s Early Masterpiece – The Shenandoah Valley

On the Confederate side, statements flew between Johnston, Beauregard and President Jefferson Davis over who was to blame for the failure to chase after and crush the enemy after the fight. For the Union, Lincoln removed McDowell from command and replaced him with George B. McClellan, who would retrain and reorganize Union troops defending Washington into a controlled/punished fighting force, known as the Army of the Potomac.