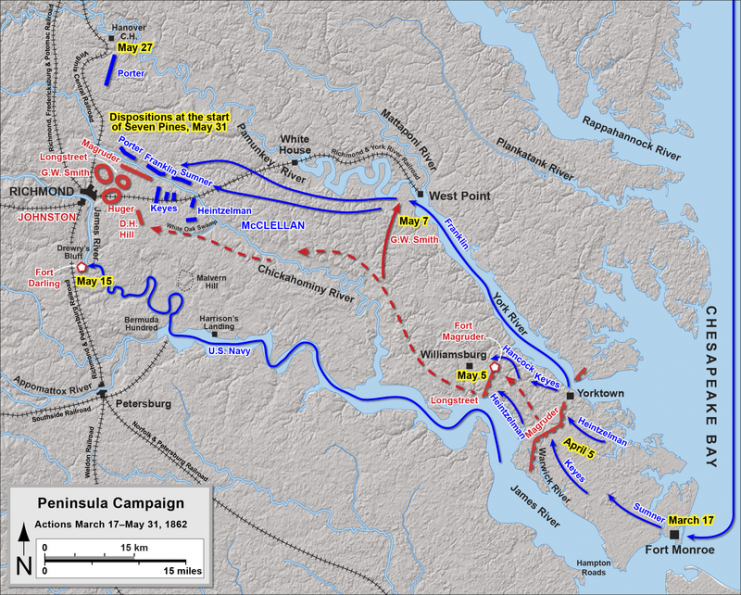

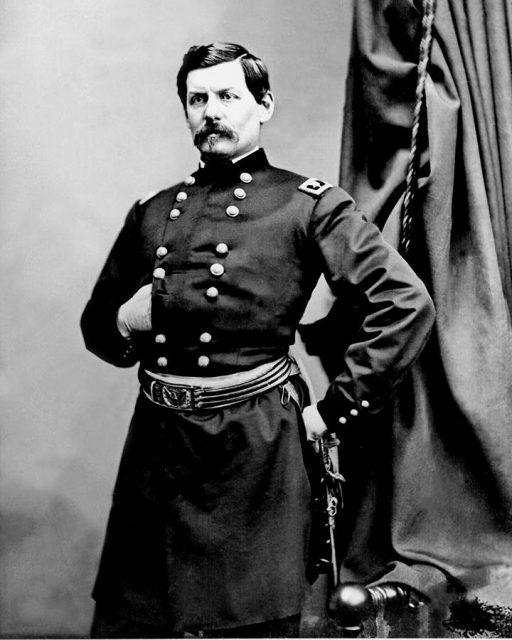

The Battle of Glendale took place on June 30, 1862, as part of the Union-orchestrated Peninsula Campaign of the American Civil War. During the end of the campaign, General George B. McClellan’s retreating Army of the Potomac became divided.

Glendale and Malvern Hill are battles that many of the famous generals of the Civil War would likely have us forget. McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign failed despite superior numbers and firepower. Lee’s extravagant battle plans rarely resembled reality and even Stonewall Jackson took a nap, missing an entire engagement.

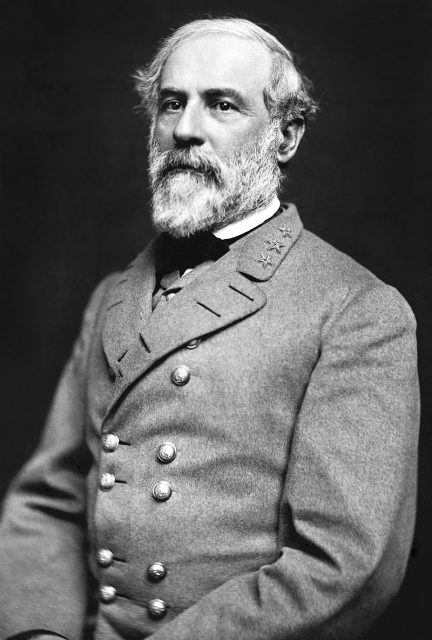

A large faction of the army occupied Malvern Hill while a smaller unit of four Corps was caught in a battle with General Robert E. Lee’s Confederate forces in pursuit between White Oak Swamp and Glendale in Henrico County, Virginia.

Lee’s series of counter-offensives against the Union Army came in such quick succession that McClellan was left bereft of bright ideas to continue his advance on Confederate territory.

Subsequently ordering his army to retreat toward the James River, “Lil Mac” left ahead of his army, aboard the gunboat U.S.S. Galena with no precise instructions pertaining to withdrawal routes for the army, neither did he place the army under the command of someone other than himself.

Like sheep without a shepherd, the Federals scampered over the tangled and densely forested, swampy area surrounding Richmond and by noon of that day, most of the Union forces had successfully trudged through waters of White Oak Swamp Creek and one-third of them were already at the James River.

Lee was abreast of the situation of things with the Federals and promptly sent his army after them in pursuit. The Confederates encountered the smaller faction of the Union forces at Glendale.

From the beginning of the Seven Day Battles, Lee’s offensive strategy was badly troubled by overly complex battle plans, geographical difficulties, and poor performances by his division commanders. These obstacles held true once more at the Battle of Glendale.

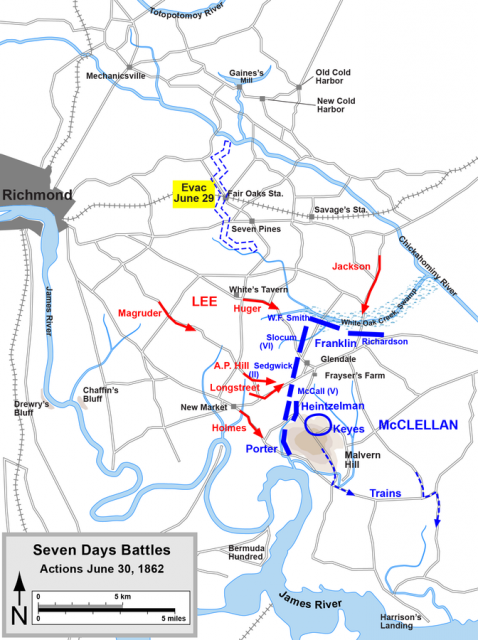

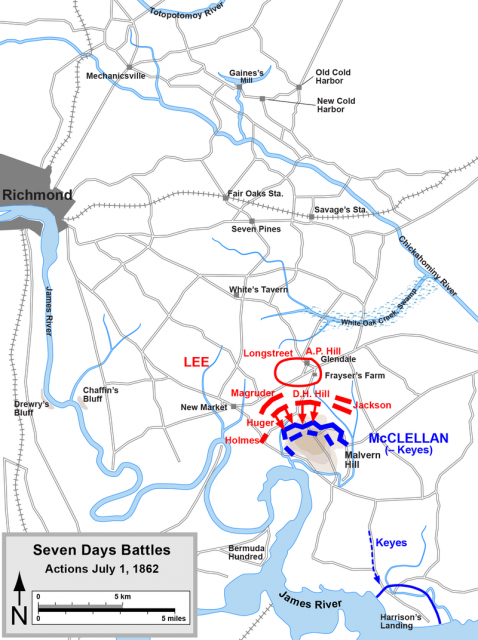

After an unsuccessful attempt to overrun a part of McClellan’s troops on 29 June at Savage’s Station, Lee figured out a new battle plan aimed at cutting off the Federals from the James River. Lee’s detailed plan called for a central attack to be delivered by Brigadier Generals James Longstreet and A. P. Hill, attacking the Union army from the west just outside the village of Glendale.

Strong support would be provided by division commanders Benjamin Huger and John B. Magruder attacking the left and right sides of the Union line.

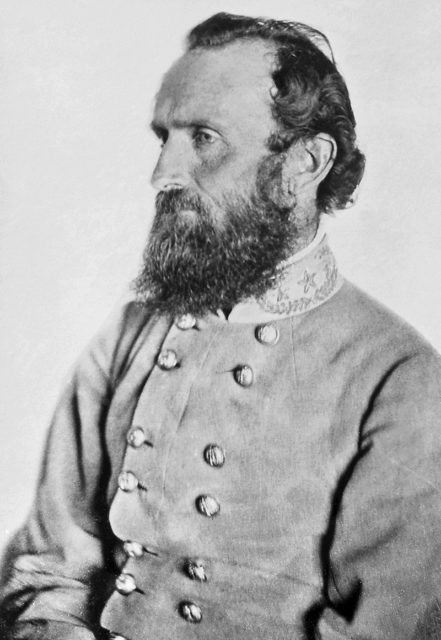

Meanwhile, Lieutenant General Stonewall Jackson, with one-third of the Confederate force, was to rebuild the bridge that was destroyed the previous day during the battle at Savage’s Station and to overwhelm the remaining Union troops positioned there, he would then march two miles south, coming up behind the Union forces which would already be engaged with Longstreet and Hill, effectively sandwiching the whole Union army.

Due to poor execution of Lee’s orders, however, only Longstreet and Hill managed to get their men into position, fighting a terrible and bloody stand-up battle beginning two hours before dawn and ending only when darkness stretched across the field.

Though Longstreet and Hill pressed hard into the Union center, eventually gaining some ground, they were unaided by the rest of the Confederate army and so unable to sustain their position.

In addition to Huger and Magruder’s failure to enter the battle, the expected support from Jackson’s troops to the north never appeared. In what may be his worst performance during the Civil War, Jackson, exhausted and tired, did not rebuild the bridge due to Union big guns and sharpshooters.

Seeing no way to cross the creek, he recalled his troops from danger and lay down to sleep under a tree. Even later, when his staff officers awakened him to report an alternate route to cross the river with infantry, Jackson ignored their findings and remained asleep beneath the tree while gunfire from Glendale sounded in the distance.

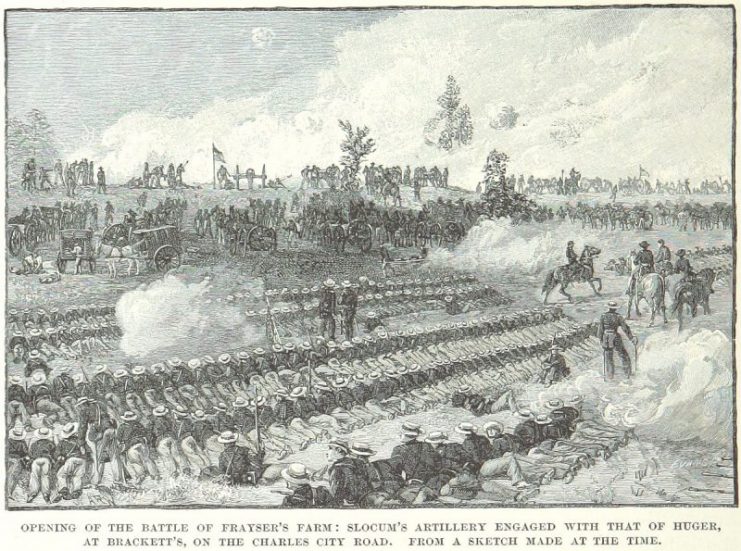

As the senior leadership retired, Confederate guns unsuccessfully tried to silence their Union opponents. In response, Hill, whose division was under Longstreet’s direction for the operation, ordered troops forward to attack the Union batteries.

Pushing up the Long Bridge Road around 4:00 PM, Colonel Micah Jenkins’ unit attacked the forces of Brigadier General George G. Meade and Truman Seymour, both of McCall’s division. Jenkins’ attack was supported by the brigades of Brigadier General Cadmus Wilcox and James Kemper.

Advancing in a disorderly manner, Kemper arrived first and charged at the Union line. Soon supported by Jenkins, Kemper managed to break McCall’s left and drive it back.

Recovering, the Union forces managed to reform their line and a seesaw fight resulted with the Confederates trying to break through to the Willis Church Road. A key route, it served as the Army of the Potomac’s line of retreat to the James River. In an effort to help McCall’s position, elements of Major General Edwin Sumner’s II Corps joined the fight as did Hooker’s division to the south.

Slowly feeding additional military units into the fight, Longstreet and Hill never mounted a single huge attack to overwhelm the Union position. Around sunset, Wilcox’s men succeeded in taking prisoner Lieutenant Alanson Randol’s six-gun battery on the Long Bridge Road.

An attack by the Pennsylvanians re-took the guns, but they were lost again when Brigadier General Charles Field’s unit attacked near sunset.

As the fighting twisted and flowed, a wounded McCall was taken prisoner as he tried to reform his lines. Continuing to press the Union position, Confederate troops did not stop their attacks on McCall and Kearny’s division until around 9:00 that night.

Breaking off, the Confederates did not reach the Willis Church Road. Of Lee’s four intended attacks, only Longstreet and Hill moved forward with any energy. In addition to Jackson and Huger’s failures, Holmes made little progress to the south and was halted near Turkey Bridge by the rest of Porter’s V Corps.

The fighting at Glendale ended that night with the Union suffering 3,800 deaths, compared to 3,700 for the Confederates. Under the cover of darkness, McClellan was able to withdraw his forces safely to a strong position three miles to the south on Malvern Hill, near the James River.

Despite sensing signs of demoralization and collapse, Lee roused his troops to another day’s fight the following morning.

The Union big guns at Malvern Hill the next day shattered wave after wave of Confederate infantry, causing Confederate Major General D. H. Hill to write later: “it was not war–it was murder.”

Following this very big victory, McClellan completed his retreat from Richmond, moving first to Harrison’s Landing on the James River, and then on to Washington, ending the Peninsula campaign.