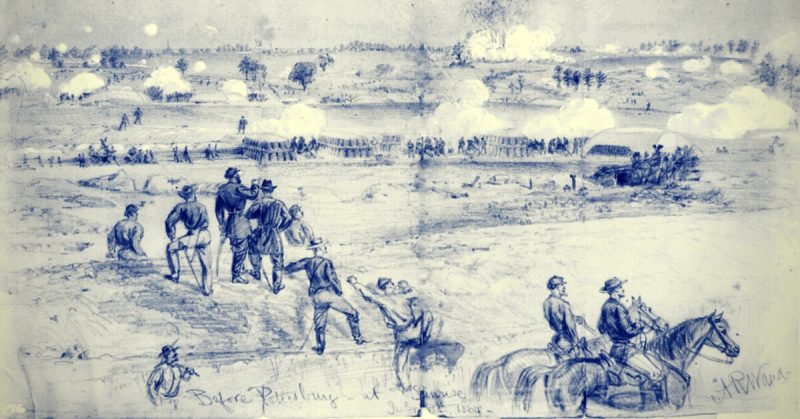

Colonel Delavan Bates waited 27 years to receive his Medal of Honor. He was awarded the prestigious accolade in 1891 for “gallantry in action where he fell, shot through the face, at the head of his regiment” on Cemetery Hill during the Battle of the Crater at Petersburg, VA in July 1864.

The “crater” was formed by 20 miles of Confederate earthworks and trenches, part of which were blown asunder by the Union, leading to chaos and debacle.

The Battle of the Crater was a tremendous embarrassment of horrific misery. It was the last straw that cemented the final withdrawal of Union Major General Ambrose E. Burnside from command.

Ulysses S. Grant called the battle “the saddest affair I have witnessed in this war.”

The idea was to blow a partition in the Confederate defenses under a mine, creating a breach that could be filled nearly instantly with Union troops. It was thought that the Confederates would not have time to come together effectively to stop it.

Things did not go as planned. The troops that were trained for this specific operation were black. At the last minute, it was decided that losing them, if it didn’t go well, would be politically disastrous for war support in the North.

They switched positions with white troops whose commander, Brigadier General James Ledlie, was reportedly drunk. He failed to brief them on the particulars of the mission.

The soldiers then had to wait longer than expected –probably in anticipatory tension – because the fuses would not light. It took hours to get them going but eventually blew a crater killing 278 Confederate soldiers.

Ledlie, still drunk, did not send his unbriefed, untrained troops in immediately as planned. He waited ten minutes. Whoever was supposed to set up foot bridges for them to traverse the trenches had not done so. They ended up crawling over and into trench after trench to even get to the crater and take action.

The black troops had been trained to move quickly within the crater and push back the Confederates. Ledlie’s men, having no idea what they were supposed to be doing, decided that the crater made a great trench for cover and parked themselves in it. The Confederates, given the time to prepare, walked up to the edge and started picking them off in what was called a “turkey shoot”.

The chaos of the battle and the Confederate’s swift retaking of the upper hand resulted in a heavy loss of Union troops.

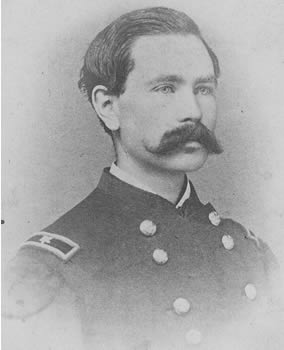

Colonel Bates

Colonel Bates was the commander of one the aforementioned troops of black soldiers trained to go into the crater. He was the very first person to enter the crater after the “turkey shoot”. It had been some time since the explosion and the terrifying aftermath. Though the soldiers were “demoralized” walking amidst the more than two hundred dead and dying, they held strong and pushed the Confederates back.

When they had succeeded and were resting, Bates was given an order from Burnside to leave the crater and charge up nearby Cemetery Hill against Confederates that were beating the Union there. He told his men that during the charge they should ignore the wounded and carry on.

As they went up the hill, Colonel Bates was shot in the right cheek with a fifty-eight caliber Enfield Ball which exited his left ear. It narrowly missed killing him instantly. His men rejected the order to ignore the wounded, knowing that the Confederates had no mercy for an officer in command of black troops.

In the melee of gunfire, they hoisted him up and carried him away to safety. By October of that year, he was well and recovered and was upgraded in rank to General in command of a brigade in North Carolina.

General Bates left service after Reconstruction. He married in 1870, two years later leaving his home state of New York to become a pioneer homesteader in Nebraska. Once his homestead claim was recognized, he moved into the town od Aurora, NB to became vice president of a bank there. He was well-loved among his neighbors and townspeople.

He was a city councilman for 8 years, county superintendent of schools, and a two-term mayor. He had four children. Even in old age, and for 16 years after the death of his wife, he remained a pivotal member of the community, organizing fundraising and implementation of a cemetery, a bandstand, and other civic projects until his death in 1919.