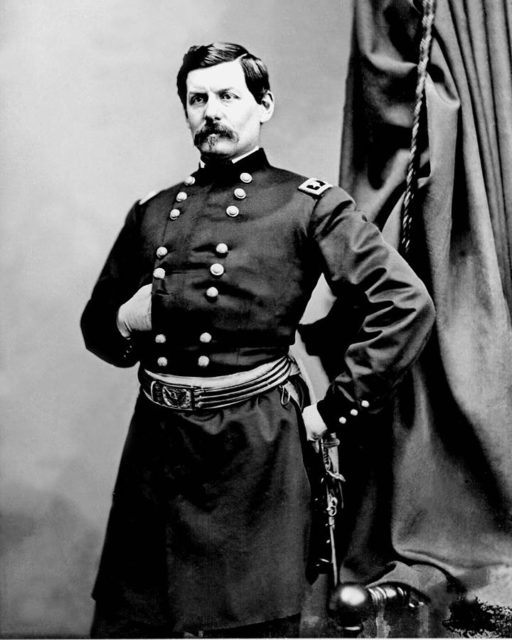

On the night of May 3, 1862, Confederate forces began a withdrawal from the defenses around Yorktown. For a month, they had been waiting for the Union army to smash them with their superior strength and firepower. Only the caution of the Union’s General McClellan had kept them alive.

As the Confederates retreated, the Union troops finally advanced. On May 5, the long-awaited clash of arms began. However, instead of a massive encounter outside Yorktown, it was a smaller delaying action near Williamsburg.

Difficult Ground

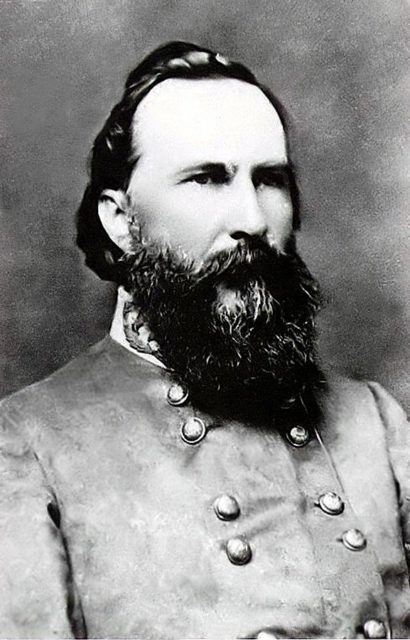

The area General Longstreet chose for the fight was perfect for his purpose of holding up the Union forces. A series of redoubts gave the Confederates strong defenses, with the intimidating earthworks of Fort Magruder sitting on a road junction at the center. On their right, the woods slowed down the Union advance, broke up their forces, and reduced their field of fire. Also, torrential rain turned the ground to mud, making even the roads slow going.

Fighting Joe Gets to Fight

Early in the morning, advancing Union forces spotted Fort Magruder. Two brigades faced Longstreet’s rearguard. On the Union right, in the relatively open ground, was General Smith. On the wooded left was General “Fighting Joe” Hooker.

Hooker had been bridling at the restraint forced on him by McClellan. On seeing that they had caught up with the retreating Confederates, the Union forces formed their line, ready to face the Confederates in battle.

First Exchanges

Hooker sent forward skirmishers to engage the Confederates in the Fort and the rifle pits in the woods. Irregular fighting between the two sides, together with the efforts of Confederate sharpshooters, kept the Union troops busy as they waited for the rest of their forces to arrive.

As the first of his artillery moved forward, Hooker tried to position it along and beside the road. That way, the cannons could bombard the fort. Confederate artillery immediately opened fire, scattering the exposed Union artillerymen. After cajoling the frightened soldiers back to their guns, the Union artillery poured cannons into Fort Magruder, silencing its guns.

By 1030, Hooker had assembled a substantial force, including machine guns. He was considering launching an attack on his left, where the Confederates seemed vulnerable. Then gunfire erupted from that part of the line. The Confederates were not weak there after all.

The Confederate Attack

The shrill sound of rebel yells announced a Confederate charge through the woods.

Fierce fighting erupted on the Union left. The 1st Massachusetts regiment used up all their ammunition and was replaced by the 72nd New York. They, in turn, were replaced by the 70th New York.

Late in the morning, Hooker’s right reached the Yorktown road. There, he had hoped to link up with supporting forces, but there was no sign of them. He sent a message to General Sumner seeking support.

Under Pressure

The fighting on Hooker’s left had turned into a full-scale battle. By advancing against the enemy, he had the confrontation he sought, but it was not the sort of conflict he wanted. Instead of the attacker, he was the defender. With courage and overwhelming numbers, Confederate infantry were pouring into his left.

As holes appeared in the Union line, Hooker sent his last reserves to fill the gaps. The line became strung out. The guns in front of Fort Magruder had to be abandoned. The supply train had not yet reached the line, and desperate men robbed the fallen to provide themselves with ammunition.

Things were looking bad.

On the Right

While Hooker’s men faced their desperate struggle, where was the rest of the Union army?

Far to the right of the Yorktown road, General Smith’s division had formed a battle line but faced little opposition. General Peck advanced up the road around 1300 but was unable to find Hooker to connect the Union lines.

On the far right, General Hancock moved forward, occupying abandoned Confederate redoubts. Ordered to withdraw by General Sumner, he delayed until 1700, when a Confederate attack made withdrawal impossible. Hancock held his ground, inflicting heavy casualties on the enemy.

Holding the Last Line

Back on the left, the Union soldiers realized they were beaten. They began to fall back in confusion.

Trying to prevent a full-blown route, Hooker set a cavalry line across Hampton Road, with orders to cut down any unwounded man who tried to retreat.

Half a mile to the rear, Hooker pulled together the last fighting line. The 4th New York Battery fired canister shot at the advancing Confederates. The hardiest of the Union soldiers fought in hand-to-hand combat against superior numbers of the enemy. Despite having been nearly hit earlier in the day, and later flung from his horse, Hooker rode up and down the line encouraging his men.

Kearny Takes Charge

Around 1500, General Kearny reached Hooker. Hooker flung Kearny’s forces in, plugging gaps in the line. Then he handed over command to Kearny, the senior of the two generals.

Kearny counter-attacked, breaking the Confederate assault and retaking ground from them. An attempt to flank the enemy was abandoned after General Emory, the man in charge, concluded that his force was too weak.

By evening, the rain had finally stopped, and the fighting died down. The Confederates withdrew, happy in the knowledge they had successfully held back the Union army.

Aftermath

The Battle of Williamsburg cost the Confederacy 1,700 casualties. In return, they inflicted 2,200 on the Union. More importantly, they bought the rest of the army the time it needed. Artillery and supply wagons had been safely extricated.

As a battle, it was inconclusive. For an army in withdrawal, it was a great success.

Sources:

Walter H. Hebert (1944), Fighting Joe Hooker

James M. McPherson (1988), Battle Cry of Freedom: The American Civil War