Very generally speaking, most American Civil War professors, informal historians, and novices can easily tick off a list of well-known and talented Confederate generals. The list usually starts like this: Lee, Jackson, Longstreet, Forrest…and goes on for quite a while.

There is little doubt that the military leadership of the Confederacy, combined with the elan of most of their men kept the South in the fight much longer than it should have been – at least on paper. Outnumbered, industrially inferior with fewer natural resources, the Confederacy could easily have folded had it not been for the skill of its general officers.

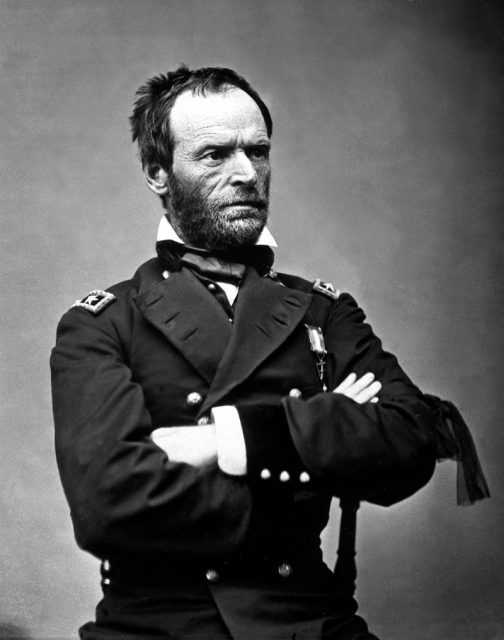

Even though the Union was victorious, the list of its well-known and talented officers usually starts with, Grant, Sherman, then…? In recent years, historians’ assessments of Union generals has changed somewhat, especially that of Grant – he is viewed as less of a butcher relying on attrition and much more of a skilled officer than had previously been believed.

Still, that leaves a lot of territory. Let’s list and briefly introduce three of the lesser known but talented Union generals other than the “Big Two” of Grant and Sherman.

Coming in a close third, at least in name recognition, is General Philip Sheridan, who after the Civil War led US government campaigns against Native Americans and then became General of the Army in the early 1880’s. Sheridan graduated from West Point in 1853, taking five years instead of the usual four due to a suspension that resulted from him threatening to kill another cadet.

In the years prior to the Civil War, Sheridan was stationed in the West, from Texas to Oregon and Washington territories. There, he led small units in actions against native tribes. Just before the outbreak of the War Between the States, he was promoted to first lieutenant, and then to Captain.

Because of his West Point connections, Sheridan (against his inclination) was initially given staff assignments involving investigations of corruption in the army, and then quartermaster general. Sheridan had a reputation as a feisty Irishman and got caught up in an internecine army squabble in early 1862. In the midst of this argument, which saw Sheridan in the right, he met General Sherman and other influential officers who secured for him a place as a cavalry commander.

Sheridan had no experience in or with the cavalry besides a rudimentary knowledge from his days at West Point, but by all accounts, he was a natural leader and took to the mounted arm of the service with flair and talent. In his first three actions (Booneville, Mississippi then Perryville, Kentucky and Stones River, Tennessee) Sheridan played leading roles.

In the first two actions, the Union was victorious, and in Tennessee, Sheridan’s quick thinking prevented a complete Union rout. By the end of 1862, “Little Phil” had been promoted from captain to major general and was recognized in the army as a rising star.

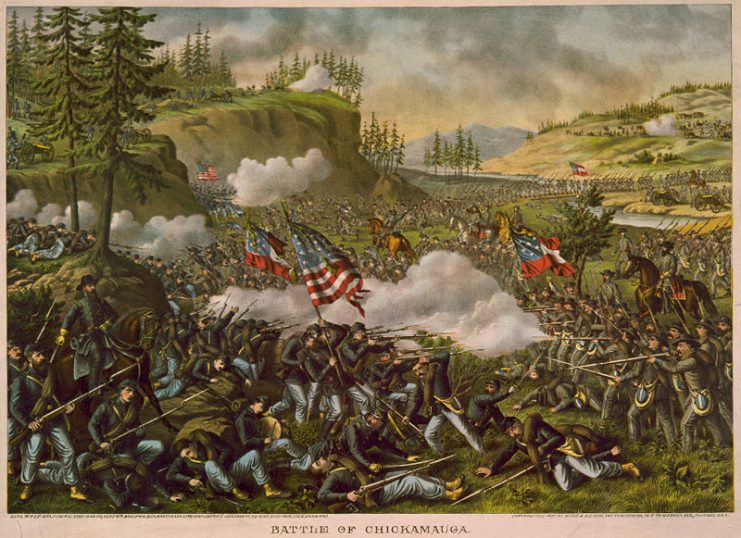

Suffering a setback at the bloody Battle of Chickamauga (Tennessee) in September 1863, Sheridan later redeemed himself at the Battle of Chattanooga two months later, playing an important role and leading his troops with an aggressive spirit usually ascribed to Southern officers. After Chickamauga, Grant, now commander of the Army of the Potomac, had Sheridan transferred to Virginia for the campaign he hoped would end the war.

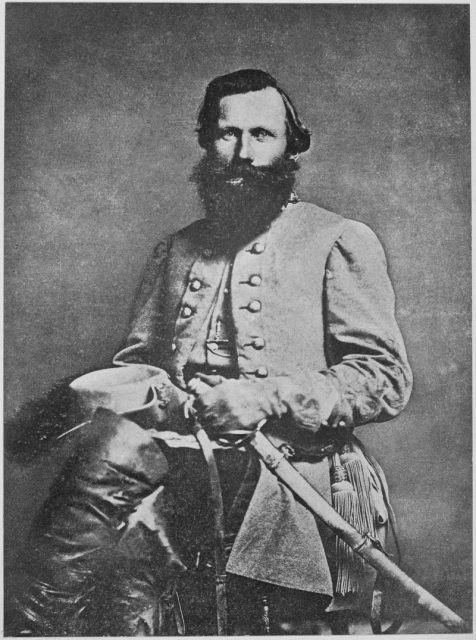

Though Sheridan had his ups and downs in the initial part of the Virginia campaign of spring 1864, he sealed his reputation when his unit confronted well-known Confederate cavalry commander J.E.B. Stuart at Yellow Tavern, which ended in Stuart’s death – a blow to the morale of the South. Sheridan led his men in a number of battles throughout the campaign, including a stout defense at Cold Harbor in June.

One of the most famous campaigns of the war was Jackson’s Shenandoah Campaign of early 1862. Both the South and North realized the importance of the Shenandoah Valley, both as a food source and as a route into the North. For those reasons, Sheridan was told to undertake his own Shenandoah campaign in 1864, which became known as “Sheridan’s Ride” in the North and infamously as “The Burning” by Southerners in the Valley.

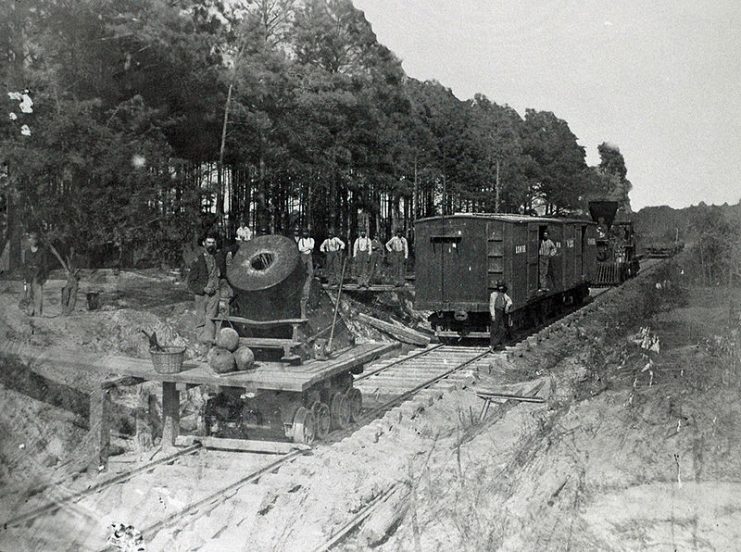

Sheridan’s campaign in the Shenandoah was in many ways a precursor to Sherman’s later “March to the Sea”, and is held up as one of the first modern examples of “total war”. Sheridan’s command burned and pillaged its way through the Valley, assuring that it could not be used to feed and transport the Confederacy ever again.

In the latter days of the war, Sheridan re-joined Grant for the final drive against Lee, assuming a corps’ command and playing a crucial role in driving Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia to its surrender at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865. Sheridan died of natural causes in 1888 at the age of 57, having held commands throughout the nation after the Civil War.

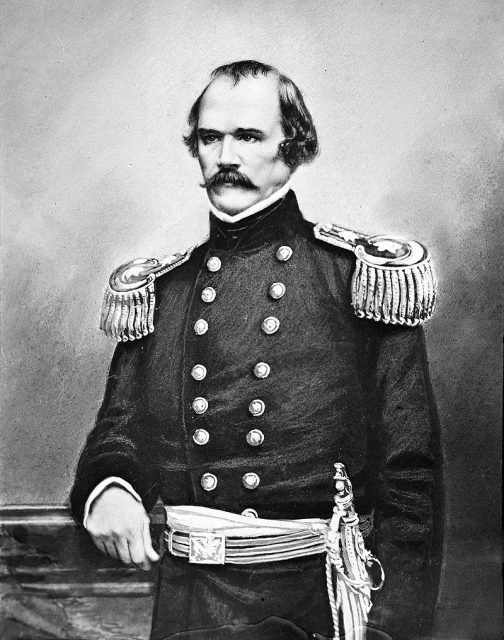

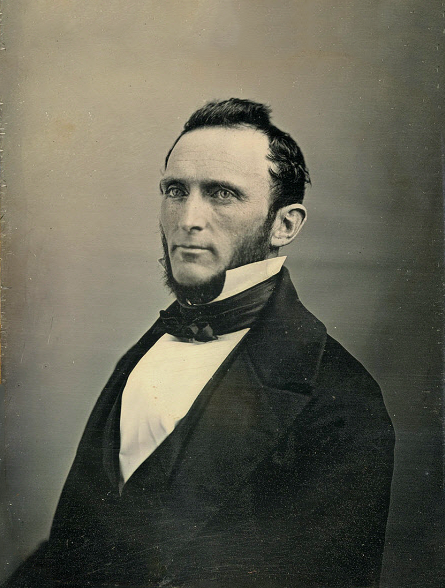

Winfield Scott Hancock became one of the most famous and admired Union heroes during the Civil War, and in 1880 almost won the Presidency on the Democratic Party ticket. Born in Pennsylvania in 1824, Hancock was named after one of the heroes of the War of 1812, General Winfield Scott. In the war with Mexico in the late 1840’s, Hancock served in Scott’s command as a lieutenant, where he served bravely until taken out of action after complications from a knee wound.

Scott’s story is in many ways a parallel of US history in the 19th century. Born less than fifty years after the Revolution began, he took part in the nations’ first war of expansion against Mexico, then played peace-keeping roles in the West between the US government, native tribes, Mormon settlers, and tried to keep the peace in “Bleeding Kansas” – the pre-Civil War in that territory between pro and anti-slavery settlers.

When the Civil War erupted, Hancock was on duty in Southern California, serving under Albert Sidney Johnston (later a leading Confederate commander), and Major Lewis Armistead, with whom he became close friends. Armistead’s death while serving in the rebel army at Gettysburg where Hancock was also in command hit the Union general hard.

Hancock initially served in the quartermaster corps but was given a field command during Gen. George McClellan’s abortive Peninsula Campaign. There, during the Battle of Williamsburg, he earned his nickname: “Hancock the Superb”, for the way he led his troops in a counter attack against the rebel army.

Hancock saw action in virtually every major battle the Union took part in in the East: Antietam, where he saved the day against Confederate attacks at the infamous “Bloody Lane”, leading his men against the virtually impregnable Southern positions at Marye’s Heights at Fredericksburg (where he received a wound to the abdomen). Recovering from his wound, Hancock was given a corps command in the Army of the Potomac which he held for the rest of the war.

During the all-important battle of Gettysburg, Hancock and his units played exceedingly important roles during all three days of the battle, holding positions on the Union left flank. Without Hancock’s quick thinking on the 2nd day, the battle might have been a Confederate victory.

On the third day, Hancock’s corps was at the spear-point of Pickett’s Charge. At a high point in the battle that day, Hancock uttered these famous words when warned away from the action by his junior officers: “There are times when a corps commander’s life does not count!” He was then seriously wounded but refused evacuation until the day was settled.

He eventually returned to command for Grant’s final campaign against Lee in Virginia, once again taking part in most of the famous battles of that campaign, and suffering his only true defeat at the Siege .of Petersburg

When the war ended, he was in the Shenandoah Valley, overseeing occupation duties. After the assassination of Lincoln, Hancock was the man chosen to lead the execution party of conspirators, something he was not comfortable with, but carried out anyway.

He then served in the West again trying to negotiate peace between the Federal government and the Native Plains tribes, and then was assigned occupation duty in the South, which met with varied success. He was also given a large command on the East Coast under President Grant.

Despite the difficulty of his positions, most people that knew Hancock, friend or “foe”, had much respect for him, and he was exceedingly popular. In 1880 he became the Democratic Party’s presidential candidate. Hancock narrowly lost the race against James A. Garfield. Hancock passed away in 1886 still holding military command of the East Coast.

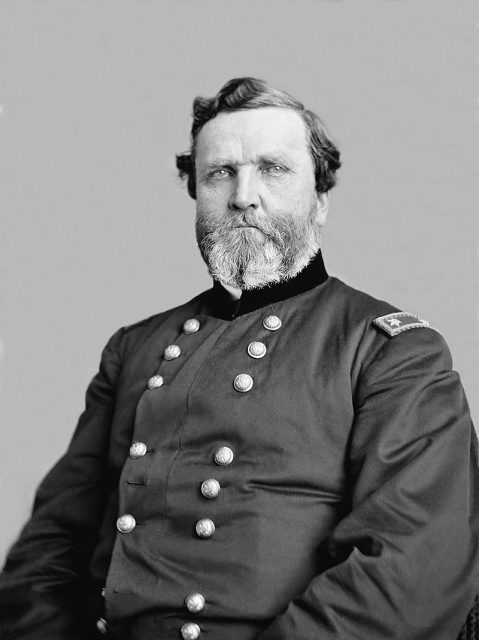

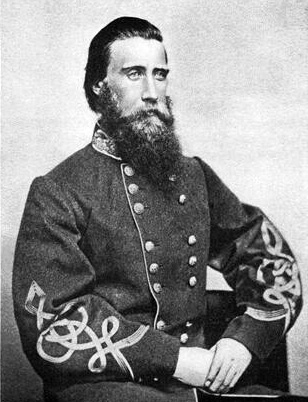

The South had “Stonewall” Jackson. The North had “The Rock of Chickamauga”, General George Henry Thomas. Thomas’ nickname suited him perfectly. Besides holding his unit steadfast in the Battle of Chickamauga in northern Georgia in September 1863, Thomas was by all accounts quiet, modest and brave.

A Virginian who was loyal to the Union, his family had had to flee their home during Nat Turner’s rebellion – unlike many, Thomas came away from that incident realizing that the actions of Turner and his followers were brought on not by simple hatred but by the yearning to throw off the yoke of slavery.

This realization played a role in his decision to go with the Union during the Civil War. Being a Virginian he was particularly hated by many in the South as a traitor, yet held the respect of his enemies on the field.

Thomas graduated West Point in 1836. He served in Florida during the Seminole War, and, like many other officers of pre-Civil War army, served in the Mexican-American War. There he gained a reputation as an outstanding artillery officer. One of his artillery comrades later went on to lead men in the Confederate Army against Thomas in the Civil War- General Braxton Bragg.

In the 1850’s, Thomas took part in actions against Native tribes in Texas, receiving a serious arrow wound to the chest – he pulled out the arrow on his own. By 1860, Thomas was one of the most experienced field officers in the army and had served in the infantry, artillery, and cavalry.

When the Civil War broke out, Thomas was on leave and went through the agonizing decision of which side to join. Many of his friends and the officers that he knew personally, such as Robert E.Lee, declared for the South, but Thomas, whose wife was from the North, stayed with the Union.

For the first months of the war, many in the Union ranks suspected him of being a Southern plant, but his devotion to duty, the love of his men and his giving of important information about Southern sympathizers in the North did much to firm up his reputation.

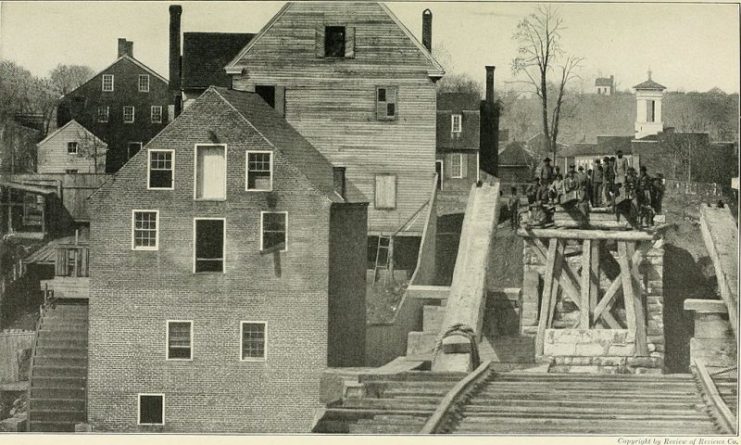

On January 18, 1862, Thomas held a training command in Kentucky but was forced into the field by Confederate actions there. At the Battle of Mill Spring, Thomas gave the Union its first victory in the field. In late 1862, Thomas took part in driving the Confederates under Bragg out of Kentucky, and in the Tennessee Campaign of 1862-63, he was deputy commander or commanded large units at Perryville, Stones River, Chickamauga, and Chattanooga.

At both Stones River and Chickamauga, Thomas’ personally led a staunch defense, preventing the rebels from breaking the Union lines, and achieving complete victory. It was future President Garfield, a staff officer at Chickamauga, who told his superior, General Rosecrans, that he had found Thomas in the field, “…standing like a rock.” Hence, the “Rock of Chickamauga”.

In 1864, Thomas joined Sherman on his “March to the Sea”, both helping supply and plan the campaign. He also faced hyper-aggressive Southern general John Bell Hood twice, at the Battle of Peachtree Creek in Georgia in the summer of 1864, and again in the Nashville Campaign in the fall of that year, defeating Hood at Nashville and the bloody battle of Franklin.

Thomas ended the war a Major General and spent 1865-69 in occupation duty in the South. When he died in 1869, he was in command of the Military Division of the Pacific in San Francisco. None of his relatives attended his funeral, but he is honored by a statue in Washington DC, town and county names in Kansas and Nebraska, and the former “Fort Thomas” is now the city of Fort Thomas, Kentucky.