In 1959, Edwin C. Fishel of the National Security Agency found files concerning the Bureau of Military Information within the records of the Army of the Potomac. After cross-referencing those files with the privately preserved documents of General Joseph Hooker, General George B. McClellan, and famous detective Alan Pinkerton, he was able to compile a true history of military intelligence during the Civil War.

Information gathering at the start of the war went down like an episode of the Keystone Cops. Pinkerton had worked for Lincoln and was a friend of McClellan’s, so even though he was a private citizen, he was hired to gather info for the Union as a “secret service.” Meanwhile, Lincoln had also hired a detective, as did General Winfield Scott, and Colonel Charles Pomeroy Stone had hired several. All of these detectives were civilians attempting to make a profit rather than soldiers trying to make a rank so it was a no-holds-barred fight that ended in a lot of gaffes. The various detectives sometimes arrested each other and often made a bungle of the entire effort.

Lincoln was growing tired of everyone’s antics – on many fronts – and after removing both General McClellan and Ambrose Burnside from leadership in the Army of the Potomac, he reluctantly put General Hooker in charge.

Hooker’s leadership techniques showed a high aptitude for organization and administration. He rallied the troops and increased morale with improved sanitation, diets, and a better furlough system, among many other things. It was through his administrative efforts that the Bureau of Military Information was born, but the real cleverness behind the intelligence is who he chose to run it.

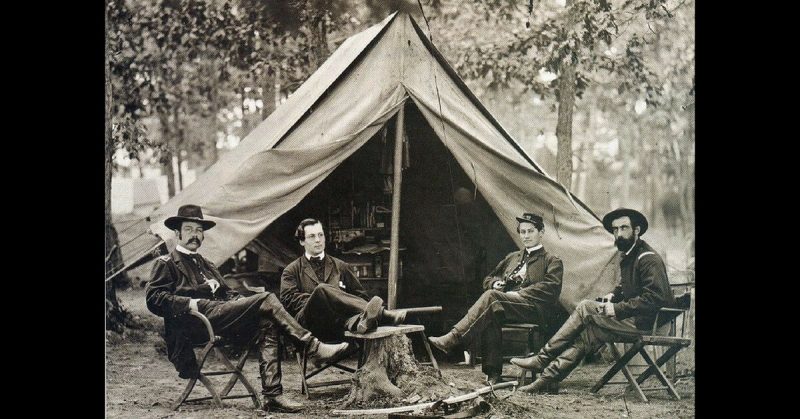

He first appointed Colonel George H. Sharpe, a man with a varied high-level work history (lawyer, diplomat, etc.) as head of the Bureau. Sharpe had replaced the John C. Babcock, who had been running intelligence for McClellan, but made him second-in-charge. Sharpe then chose a captain with ties to the immediate area, John McEntee, to head up the rest of the spies who were recruited from enlisted men and local citizens.

Hooker placed a middle-man between them – General Daniel Butterfield, through whom intelligence was filtered between the Bureau and Hooker. Butterfield also provided Sharpe with guidance and support.

While Hooker set up the foundation for the Bureau, it was Sharpe that was the true architect. He established detachments, interrogation policies and procedures, and his own scouts that moved at his command rather than that of the cavalry. Once he had reporters, the Signal Corps, cryptanalysts, and other varied sources working for him as well, the Bureau became a full-fledged, organized operation.

Like himself, Sharpe’s spies were well chosen. One was so good that he convinced the Confederates to give him a 120-mile tour of their front and rear lines – and he maintained his ruse for the ten days that they entertained him.

The Bureau was dissolved in 1865 at the war’s end after assisting General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox and playing a pivotal role in the paroling of Confederate General, Robert E. Lee.

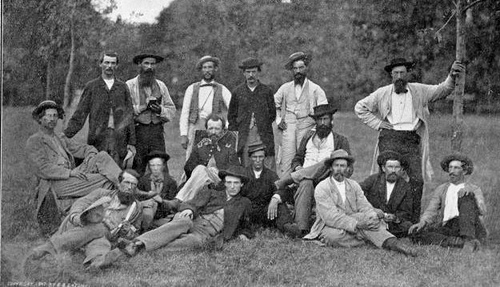

The Bureau of Military Information consisted of nearly 70 spies, 10 of whom were killed while in service.