Reliable Confederate spy records are hard to find. When Union troops were on their way to the South’s capital in Richmond, the Confederate Secretary of State, Judah P. Benjamin, panicked and burned every bit of them that he could find. Diligent historians have, however, been able to piece together a lot of the story.

What is known is that the South’s intelligence efforts were full of intrigue, sabotage, and fascinating true tales that were exciting enough to seem more like legend than reality.

The Confederacy’s particular brand of intelligence was made up of a mishmash of various sects of spies and saboteurs. It included a Signal Corps, the Secret Service Bureau, arsonists, disinformation specialists, guerrilla men, and rabble-rousers whose job it was to set Southern passions on fire against the Union and demand secession.

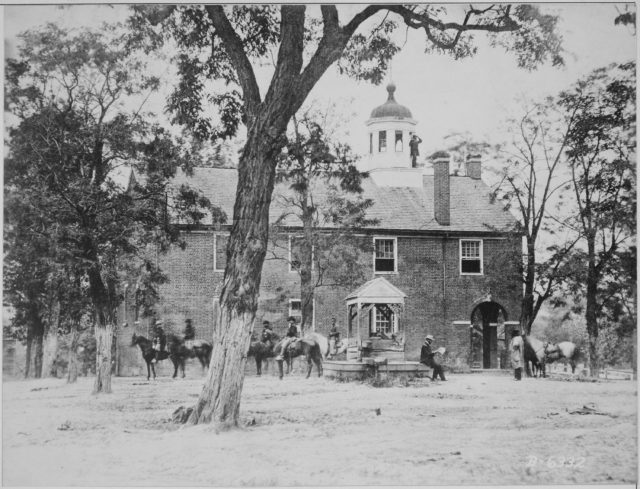

The building of the Southern spy network started early on in Washington, D.C. itself. When Virginia was in limbo between having seceded but not yet having joined the Confederacy, the governor of that state, John Letcher, began recruiting spies while he had an open loophole of sorts. He had been a recent Congressman, so he knew many people on the Hill, both in office as well as in administrative service. Unelected workers were usually from Virginia and shared Southern ideals. There were also sympathizers among the elected. It was from this pool that the first Confederate spies were drawn.

Letcher had the brilliant idea to recruit Rose Greenhow, a well-connected Washington socialite, through a handler of sorts – Thomas Jordan.

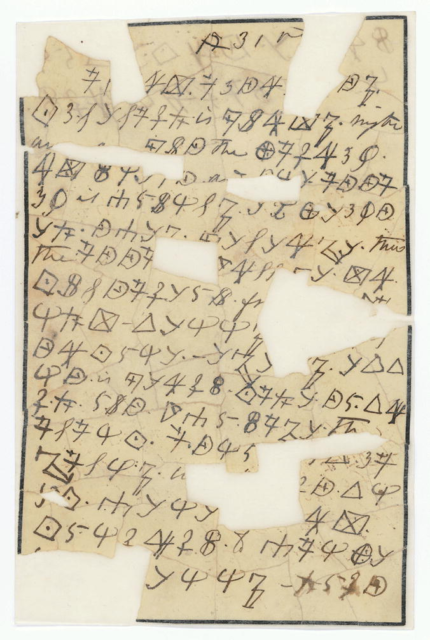

Both were clever choices. Jordan taught Greenhow a cipher and he took a spy name with which she was supposed to communicate coded messages to him. As the spy network grew, she was able to send him messages coded in cipher and symbolic words through a series of shopkeeps, couriers, and fellow spies until they reached Jordan who would pass them up the chain of command. This highway of information was called the Secret Line.

Besides Letcher’s crew, Washington was also home to the Secret Service Bureau, a division of the Confederate Signal Corps. Organized and run by Major William Norris, it was also a “secret line” but one that went deep into Union territory and beyond into Canada and Europe.

Agents inconspicuously ensconced in the North sent messages, mostly through stories and ads in newspaper columns, to the Southern front. Working with postmasters in Mason Dixon states that had Southern sympathies, Southern operatives would get copies of these messages through a very complicated system of forwarding mail from one place to another in a relay from the North to Virginia. This secret line was called “The Government Route.” Each dispatch made an arduous journey that often involved being hidden in cow manure and bumped along dusty roads in farm carts.

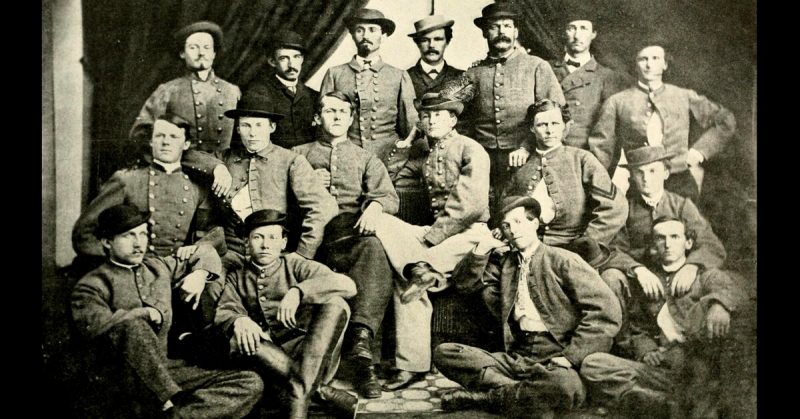

Outside Washington, cavalry scouts and guerrillas were hopping trains and taking documents off Union officers and otherwise creating mayhem with all of the drama of a Rebel Yell. John Mosby’s Partisan Rangers, for instance, would reconnoiter an area, then quick as lightning on the appointed day come in and raid it, often for espionage purposes, and then disappear in the blink of an eye, earning Mosby the nickname, “The Gray Ghost”.

Of course, there were operations by scouts, such as the Coleman Scouts, that were a bit less brash and obvious. Scouts stole plans, maps, and other intelligence from under the noses of Union Generals and made sure they found their way to Confederate officers. One such scout, Sam Davis, was caught in the act, and his fate was that of any military man caught out of uniform spying – death by hanging. Like Nathan Hale before him, his death became a motivator for a weary populace trying to make it through the rest of the war. Even after the loss of the Confederacy, the clergy were still known to treat him as a near saint.

As the war drew to a close, Southern intelligence, espionage, and covert affairs amped up to the point of destruction. The Confederate Army of Manhattan, a covert agency of eight, began setting fire to 19 hotels, a theater, and “for a reckless joke,” P.T. Barnum’s American Museum, all on one night. They all escaped initially, but their mission failed. Very few of the fires did any real damage and all were put out.

The entire act was driven by petulance. The operation had been meant to cause disruption and distraction on Election Day 1864, but their plan had been caught out and squashed by a double agent. Therefore, they executed the plan a few days later, possibly under the influence of drunken revelry.

“The Museum was set on fire by merest accident, after I had been drinking, and just for the fun of a scare.” – Robert Cobb Kennedy