It has become an accepted historical fact that the South could not have won the American Civil War. The North’s advantages in finance, population, railroads, manufacturing, technology, and naval assets, among others, are often cited as prohibitively decisive.

Yes, the South had the advantage of fighting on the defensive, this with interior lines, but those two meager pluses appear dwarfed by the North’s overwhelming strategic advantages, hence defeat virtually a foregone conclusion. But if strategic advantage alone was always decisive in warfare, then names like Marathon, Cowpens, Rorke’s Drift, and Cannae would today be meaningless, and they are not.

Indeed, there are times when the decided underdog wins in war, and there was one day in 1862 when the stars aligned, so to speak, to offer the South a victory of such magnitude that the Civil War might have ended in its favor.

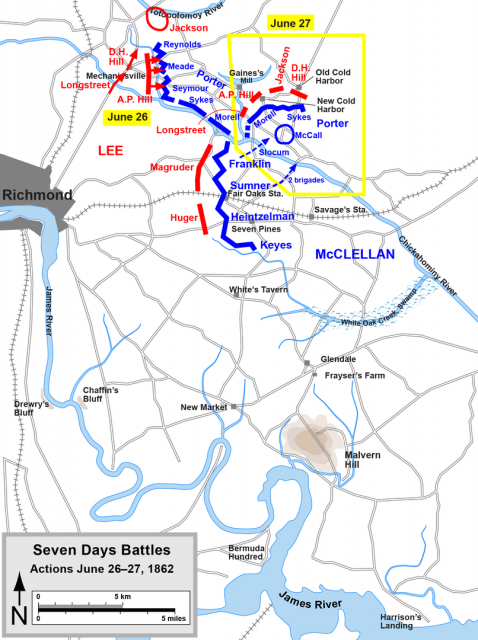

It was June 30, 1862, and for days the Federal Army of the Potomac had been in retreat from Richmond toward the James River in a series of actions later named The Seven Days.

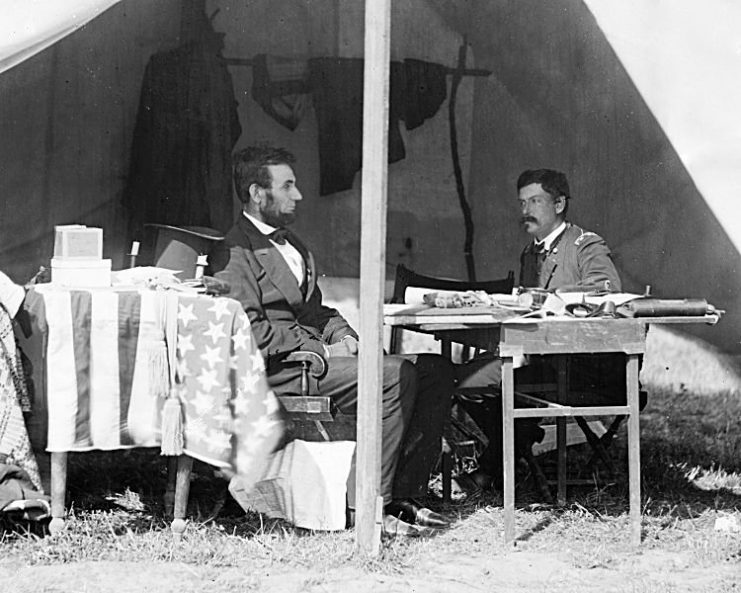

Their leader, General George McClellan – believing erroneous intelligence reports and Confederate misinformation – was fleeing an enemy he fancied 200,000 strong, when in fact the Rebel army was no larger than his own, about 90,000.

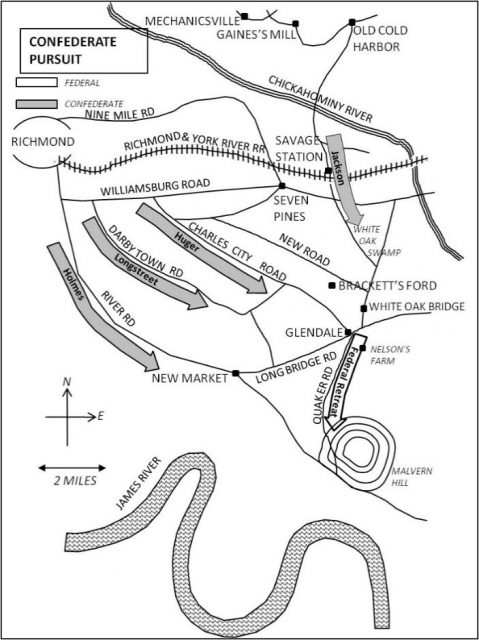

The Yankees had already fought several sharp actions at Beaver Dam, Gaines’s Mill, and Savage Station. Now the Federals were marching in strung-out columns on the few roads leading south, while the Confederates had the advantage of a series of roads that ran east and west.

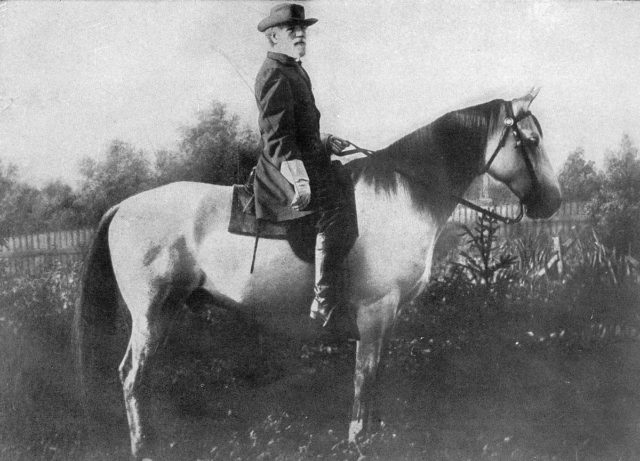

After attempts to break the Federal line at White Oak Swamp had failed, General Robert E. Lee, the recently appointed Confederate commander, glanced at his map and immediately grasped his good fortune, for the road network below the swamp appeared to offer a once in a lifetime opportunity.

The Federals were headed for Harrison’s Landing on the James, and Lee realized that, due to the lay of the land, he had one last chance to damage the Yankees before geography turned in their favor. The Confederates could use three east/west roads to attack the Federals, while at the small village of Glendale, the Yankees would be bottlenecked onto only one north/south route.

Thus, if Lee could take Glendale at the proper moment, he could slice the Federal Army in two, and the opportunity for their envelopment and destruction would be his. It was almost too good to be true.

Orders were issued immediately. Stonewall Jackson was to attack the Federal rear at White Oak Swamp, thus holding the entire Union rearguard in place. A division under Theophilus Holmes was to cannonade whatever Federals had managed to reach Malvern Hill, south of Glendale, likewise keeping the Yankees pinned down there.

Meanwhile, Longstreet and Huger’s divisions – a force of over 40,000 – would burst through the Federal retreat at Glendale, breaching their long line of march. It was a simple, even brilliant plan. It need only be implemented.

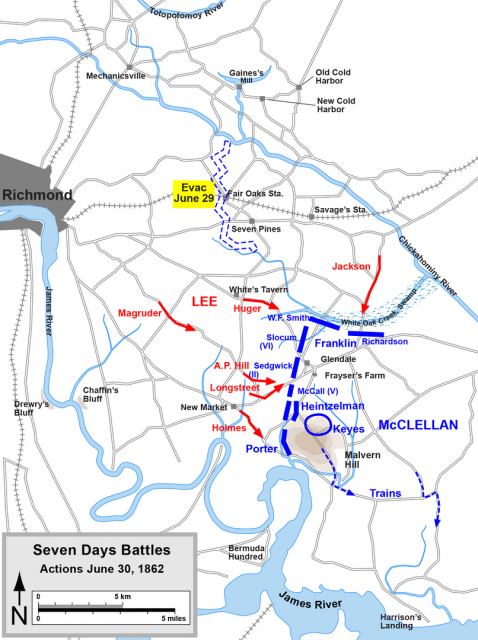

Adding substantially to Lee’s design, but unknown to him at the time, General McClellan, in what can only be described as a psychological and moral breakdown, had fled his army for the gunboat Galena on the James, appointing no second in command, thus leaving his troops behind to fight on their own hook.

Therefore, when Lee struck, the entire Federal Army – five full corps – would be leaderless and incapable of internal cooperation or defense, hence utterly ripe for destruction. If all went as planned, there was a good chance that by nightfall, June 30, the Army of the Potomac might no longer exist as a coherent fighting force, and the Army of the Potomac was President Lincoln’s primary fighting machine.

But warfare is a particularly fickle undertaking, the best plans meaningless without officers capable of executing them. For the Confederates, things, to say the least, did not go as planned.

Huger, marching east toward Glendale on the Charles City Road, became flummoxed by a sea of trees felled by Federal pioneers and, as a result, his division failed to move or fire a single shot near Glendale that day.

South of Glendale, Holmes, approaching Malvern Hill on the River Road, was spotted by Federal gunboats, and dispersed in pandemonium by an avalanche of naval artillery fire.

Worst of all, Stonewall Jackson (probably physically exhausted from his Shenandoah Valley Campaign, recently concluded) simply fell asleep under a large oak at White Oak Swamp, his entire Valley Army accomplishing nothing.

Only Longstreet would perform as ordered. Despite all the Confederate bumbling, late in the day he ordered his troops forward in an effort to seize the Quaker Road, the one avenue that led south from Glendale to Malvern Hill.

Before his hasty departure, McClellan had been advised to defend Glendale by an observant aide, hence several Federal divisions had been assembled in a loose screen west of the village. By late afternoon, both sides grasped the desperate situations they faced (for the Federals annihilation, for the Rebels a potentially war changing victory), and the fighting around the village became some of the fiercest and most violent during the war.

Combat raged back and forth, until a single brigade of South Carolina infantry under General Micah Jenkins managed to break through and take the Quaker Road, thus cutting the Federal Army in two. At that moment, only 1/3 of McClellan’s army had reached Malvern Hill, while 2/3 remained at, or north of Glendale. Despite all the day’s failure, Lee’s plan remained in play, envelopment still a possibility.

But a reserve Confederate brigade meant to support Jenkins, mistook his Rebels in the smoke and twilight for Yankees, and began firing into the South Carolinians, ultimately forcing them to withdraw.

Before Longstreet could rush supports forward to retake the road, numerous brigades of Federal infantry began converging on Glendale from White Oak Swamp – where they were unneeded due to Jackson’s inactivity – and conveniently plugged the gap in the Yankee line.

When Longstreet tried to retake the Quaker Road, the Rebels ran headfirst into this fresh Federal infantry. The battle momentarily flashed anew, only then to sputter-out in the closing darkness. Late that evening the Yankees withdrew their entire force through Glendale and consolidated on Malvern Hill, precisely the result Lee had feared.

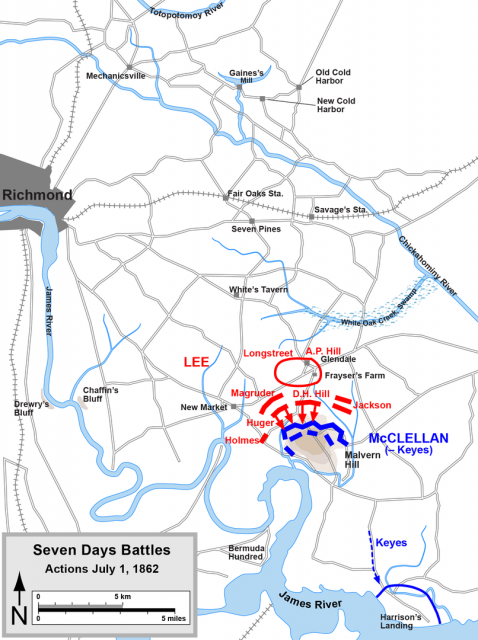

Lee, furious with his junior lieutenants, had little choice but to attack the Federals, now consolidated atop the heights, or let McClellan’s army slip away undamaged to the James. Unfortunately for the Rebels, the Battle of Malvern Hill was just as botched as was the previous day’s action at Glendale, and Malvern Hill proved a Confederate disaster.

The following day the Federals withdrew unharried to Harrison’s Landing on the river, having inflicted a punishing defeat on Lee’s army. After all the fury and activity of the Seven Days, the stunning possibility of victory that stared the Confederates in the face at Glendale – that was there, in fact, for the taking – became lost in the remaining tumult of war.

So lost, in fact, that to this day the engagement goes by any number of names including Frayser’s Farm, Charles City Cross-Roads, Nelson’s Farm, New Market Road, and Riddell’s Shop, to name but a few.

Soon thereafter Lee reorganized his senior lieutenants, but never again would he be presented with an opportunity remotely as ripe with potential victory as he had at Glendale. Douglas Southall Freeman, one of Lee’s biographers, wrote “It was the bitterest disappointment Lee had ever sustained, and one he could not conceal.

Victories in the field were to be registered, but two years of open campaign were not to produce another situation where envelopment seemed possible.” Likewise, when ruminating over the failure at Glendale years later, Confederate General Edward Porter Alexander wrote, “When one thinks of the great chances in General Lee’s grasp that one summer afternoon, it is enough to make one cry over the story how they were all lost.”

Burials Discovered at the Alamo in Texas

And lost they were. Jackson would return to fighting trim, of course, but on the one day Lee needed him at his best, the exhausted general slumbered the afternoon away, and the Army of the Potomac survived to fight another day. Upon such slim, almost inexplicable oddities, do the spokes of history at times turn.

Jim Stempel is the author of numerous articles and eight books on American history, spirituality, and warfare. These include The Battle of Glendale: The Day the South Nearly Won the Civil War, and his most recent, American Hannibal: The Extraordinary Account of Revolutionary War Hero Daniel Morgan at the Battle of Cowpens. For a full list of his books please go to: amazon.com/author/jimstempel