In an attempt to force their way into the last Confederate stronghold in Mobile, Alabama, the Federals launched two separate assaults on the Spanish and Blakely Forts on April 2, which reached its climax on April 9, 1865 with the surrender of the Confederate army.

After the terrible defeat of the Confederate Army of Tennessee in the fall of 1864, part of that army was sent to strengthen the Mobile defenses, increasing its fort populations to almost 10,000 troops.

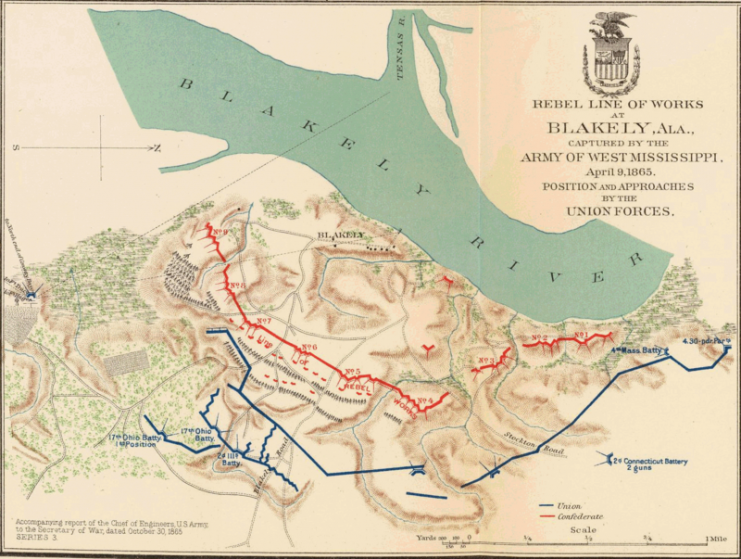

Fort Blakely was a formidable entrenchment consisting of nine connected forts, bunkers, and 41 artillery pieces including mortars. It was protected by many ironclad ships of the Confederate Navy.

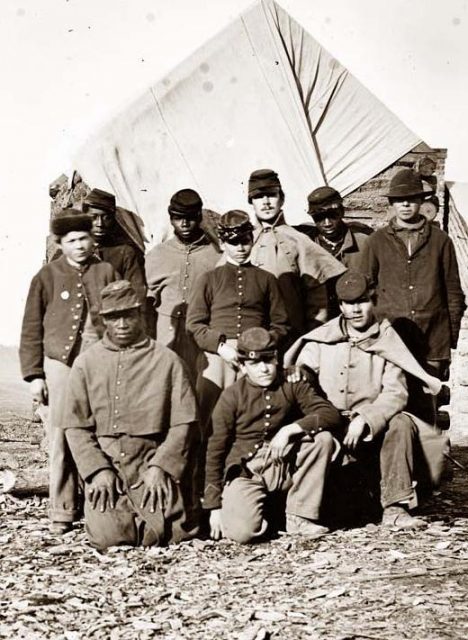

Both the Union and the Confederate soldiers who fought at Spanish Fort and Fort Blakely were experienced fighters who had partaken in almost every major fight that had happened in the lower Mississippi River Valley.

It was not until the spring of 1865 that General U. S. Grant made troops available to Major General Edward Canby for the Mobile Campaign to begin. The plan was to attack Mobile from the eastern shore of the bay, and disarm the Spanish and Blakely Forts, four miles north on the east side of the Tensaw River.

Fort Blakely now stood as the only significant Confederate resistance east of the Mississippi River. The Confederates, although at a massive disadvantage in terms of army strength, were making their last stand there. After hearing news of Spanish Fort’s fall, they knew it would only be a matter of time before Blakely was taken.

Canby’s plan was to approach Mobile from two directions. One group of the Union army was to advance from the lower part of Mobile Bay to Spanish Fort. The second group was to progress from Pensacola and center their efforts on Blakeley.

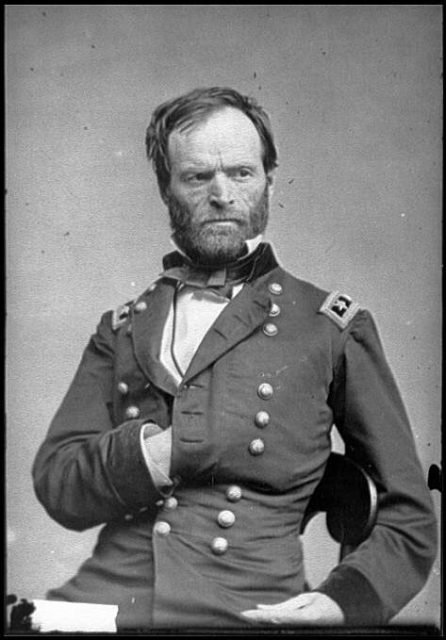

Advancing forward, the troops would knock down the marshland forces of Fort Huger and Fort Tracy, then move eastward across the Tensaw and Mobile Rivers into the city. Major General William T. Sherman suggested this route in a letter to Canby.

On the west, Mobile was surrounded by three lines of strongholds mounting 300 heavy artillery guns. Water approaches to Mobile were defended by a series of underwater obstacles, an island, and troops on shore in the east. It was said to be the most heavily defended city in the Confederacy.

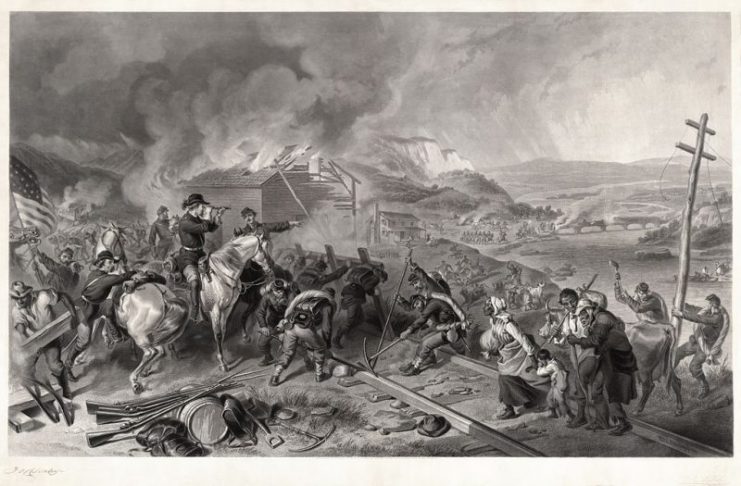

Upon reaching Spanish Fort, Canby’s troops began a 13-day attack that took place from March 27 and April 8. The incomplete Confederate lines were overrun and the fort was taken, leaving the surviving soldiers in the garrison with only one course of action: abandoning their positions and fleeing by river boats to Mobile.

The Federals marched on, 16,000 strong including 5,000 African American soldiers, under the command of Brigadier General John Hawkins to Fort Blakely, which was now defended by the combined forces of 4,000 gallant Confederate troops under the command of Brigadier General St. John Liddell, and the Confederates that had fled with Gibson from Spanish Fort.

Meanwhile, the second column of 13,000 Union soldiers, commanded by Brigadier General Frederick Steele, moved out from Pensacola on March 20 with instructions to take Fort Blakely from the rear. They moved northward, giving the impression that they were heading toward Montgomery, Alabama.

However, at the railway track at Pollard, Alabama, just 50 miles north of Pensacola, the column turned west toward the Tensaw River and then moved south to launch an assault on Fort Blakely.

Steele’s column arrived at Fort Blakely on April 1 and seized a Confederate infantry outpost in the afternoon. The next day, a heavy battle began as the Union infantry and light artillery moved into position opposite Blakely’s strongholds.

With the artillery bombardments providing cover for the Union soldiers digging trenches, they continued working their way closer to the fort. Despite the Confederates’ efforts to halt their movements, the digging continued non-stop. After a series of artillery duels and skirmishes, the day for the Union’s direct assault finally came.

The 83rd Ohio Infantry was to lead the other units of the Union Army charged with assaulting Fort Blakely. They received orders to proceed with the final assault, and on the evening of April 9, they proceeded into the ravine with not so much as a thought for their safety.

The troops soon came into contact with Confederate skirmishers as they advanced. Both parties fired upon each other, but the Confederates were outnumbered, and the advance progressed.

The fleeing Confederate skirmishers hastened to their positions at Redoubt 4, hailing the other Confederates to cease fire. Confused and nervous, the Confederate Army waited to get a full grasp of the situation at hand, as they watched their skirmishers hastily retreat.

Their grips firmly tightened once again on the triggers of their weapons, anticipating those in pursuit. But however quickly they realized how costly their lapse in firing was, it was not enough to prevent the Federal troops from surrounding them.

Read another story from us: The Drafts – Building The Armies Of The American Civil War

With no way to escape, the Confederate troops at Redoubt 4 were captured and taken prisoner. The other redoubts were also seized, and in a matter of minutes, Fort Blakely was taken along with over 3,000 prisoners. Among them was General Liddell, who had tried to stop the inevitable and failed.