Impossible Odds

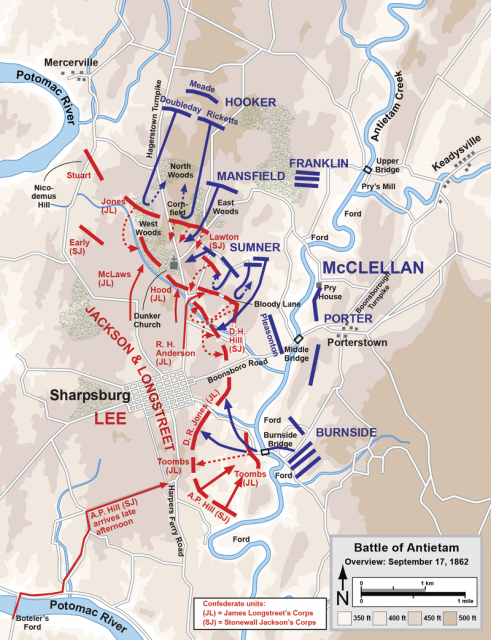

The ability of 450 resolute Georgians to stave off 12,500 Federals, preventing them from crossing Antietam Creek for several crucial hours, has to go down as one of the great stands of the Civil War. It was a Confederate Thermopylae. And the unlikely force behind this tactical masterstroke was Brigadier General Robert Toombs, age 52, a hard-drinking, irascible man—and failed candidate for president of the C.S.A.

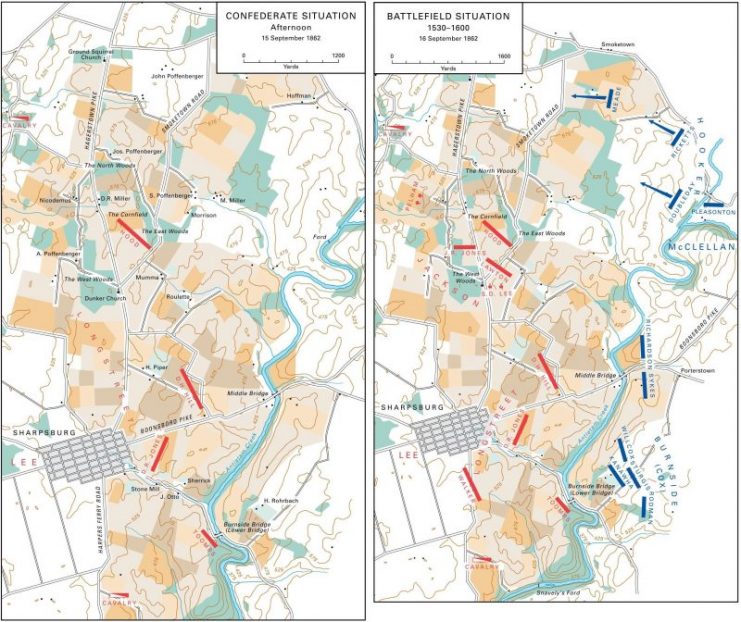

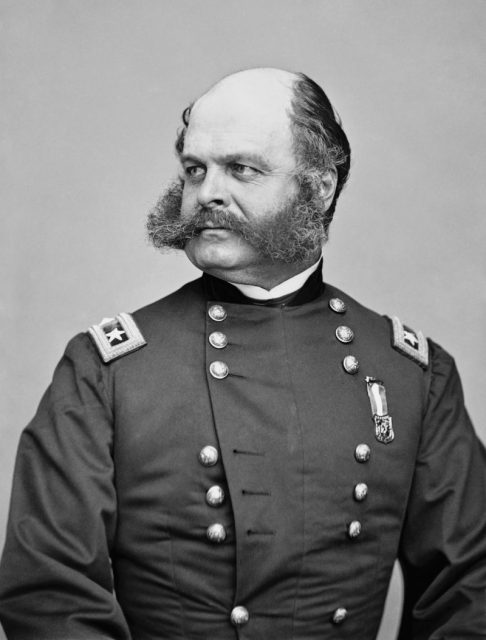

Sometime after 9:00 AM, Ambrose Burnside, commanding the Federal IX Corps, issued the attack order. Toombs’s tiny band of Georgians awaited them.

Digging In

Most of these soldiers were subsistence farmers, who worked the red clay hard, growing corn and oats. If there was anything these Georgia farm boys understood it was land. Relying on keen instincts, they had converted the steep bluffs on their side of the Antietam into a formidable natural stronghold.

Using bayonets and the halves of pilfered Yankee canteens, they had dug rifle pits into the bluff-sides. (A regulation Union canteen consisted of two convex pieces of tin, soldered together. Split one in half and you had a pair of very serviceable spades.)

To bolster their positions, they had stacked stones and piled branches and foliage. In contrast to conspicuous Federal blue, they were wearing dusky homespun uniforms that blended nicely into their surroundings. These Georgians were among the most shoe-deprived in Lee’s raggedy army. They didn’t mind so much; they valued the honesty of their bare feet on the rough earth. They were ready.

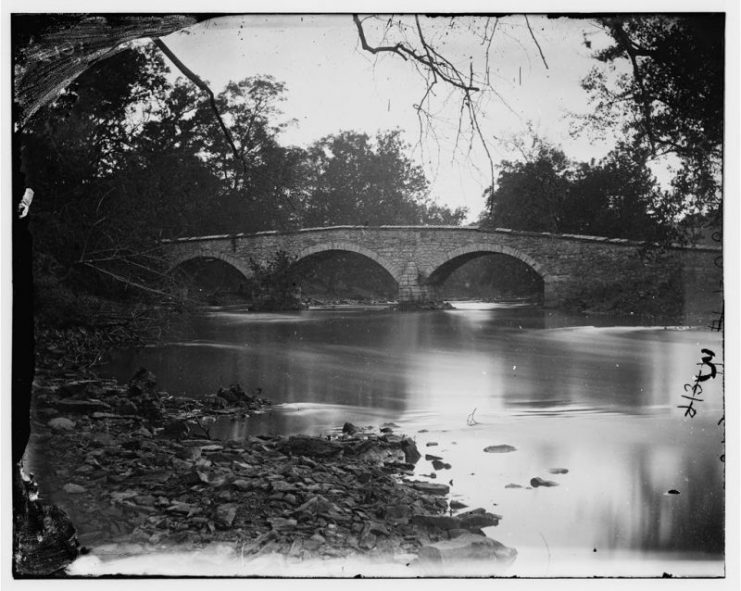

The Swift Flow of Antietam Creek

Burnside’s Federals began their attack with no inkling of how many Confederates opposed them. Toombs’s men were so well concealed, the Rebel artillerists kept up such a steady cannonade, that it could just as well be 14,000 as 450.

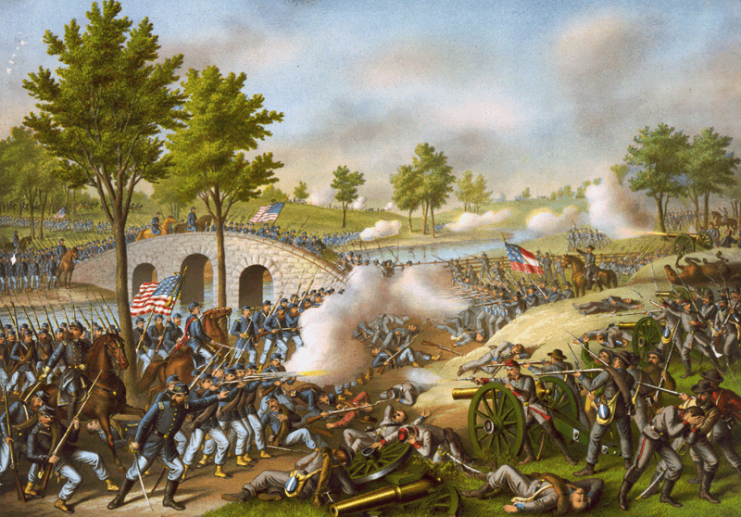

The Federals only knew that they faced a series of formidable obstacles. First they had to climb down the steep bluffs on their side of the Antietam. Then they had to dash across the 100-yard plain leading to the creek, all the while exposed to withering fire.

At the creek bank, the Federals had two options, neither one attractive. They could attempt to cross the Rohrbach Bridge. But it was only 12-feet wide; the bridge could become a bottleneck, siphoning soldiers into a narrow chute, easy marks for the Georgians who would be firing almost straight down at them. Or they could attempt to locate fording spots.

Antietam means “swift flowing water” in the language of the Delaware Indians. Pity the poor soldier forced to plunge down a creek bank, encumbered by a musket and gear, then wade through swift water of unknown depth, before climbing the opposite bank, taking enemy fire all the way.

Strength in Deceiving Numbers

As a consequence, Burnside’s attack was cautious and piecemeal. Soldiers entered the battle in dribs and drabs, one or two regiments at a time, charging down the bluffs only to be repulsed by the Rebs. A group of 3,200 men (a quarter of the Union IX Corps) got hopelessly lost in the woods searching for a fording spot.

Every time they emerged from the trees, Toombs’s Georgians opened fire. Yet again, the natural conclusion was that the bluffs on the west side of the creek were crawling with Rebels. Incredibly, the Georgians were defending a 1,650-yard front with a force the size of a Saturday night hoedown.

What a ruse! It was the finest hour for Toombs, a man with—shall we say—a colorful past.

Source: Library of Congress

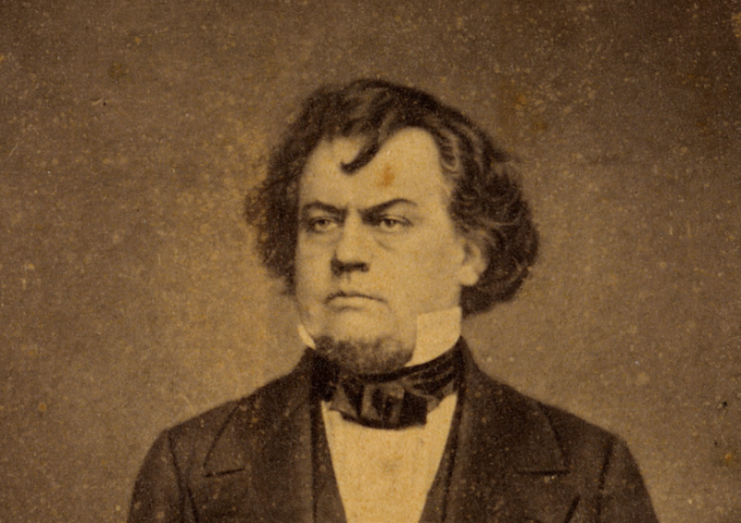

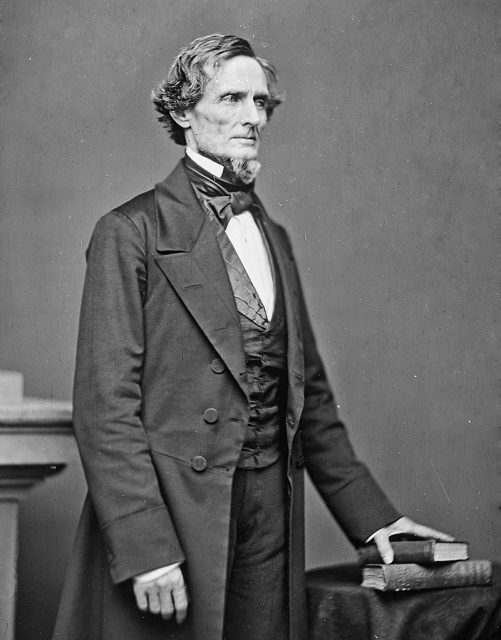

The Unlikely Rise of Toombs

During his Georgia youth, Toombs was devoted to physical pursuits: riding, hunting, and brawling. He grew to be over six feet tall with dark roving eyes, a shock of unkempt hair, and a penchant for disheveled dress. He attended Franklin College (forerunner to the University of Georgia in Athens), where he got into a running feud with two brothers.

In the course of several days of sustained violence, Toombs threw a heavy wash bowl at one brother, pointed a pistol at the other, and charged both brothers wielding a knife in one hand, an axe in the other. This got him expelled. But the silver-tongued Toombs managed to talk his way back into the school, only to be expelled a second time. Somehow he managed to graduate from University of Virginia law school — dead last in his class.

Unbowed, Toombs set up practice as a lawyer in Washington, Georgia. At a time when a young Abraham Lincoln was travelling Illinois’ Eighth Judicial Circuit, Toombs traveled his state’s Northern Circuit, making a name for himself. In 1845, Toombs was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. (Two years later, Lincoln was elected to the same body).

As the South dug in over states’ rights and slavery, Toombs’s political prospects just kept rising. He was elected to the Senate. His rhetoric soared. As an orator, Toombs had extraordinary skill and power. “Defend yourselves! The enemy is at your door;” he boomed on the floor of the Senate in early 1860, “wait not to meet him at your hearthstone; meet him at the doorsill, and drive him from the Temple of Liberty, or pull down its pillars and involve him in a common ruin.”

His “Doorsill” speech was widely reprinted, emboldening Southerners and unsettling the North.

A Failed Bid for President of the Confederacy

When the South broke from the Union, Toombs might even have assumed the highest office in the fledgling Confederacy, but for an embarrassing incident. In February of 1861, delegates from the recently seceded states convened in Montgomery, Alabama, to select a provisional leader.

Toombs’s name was at the top of the list. But he got stinking drunk at a convention banquet—and at a couple other public events, too—making a fool of himself. The presidential nod went instead to temperate Jefferson Davis, a man that Toombs despised. The two had once come within a hairsbreadth of fighting a duel after Toombs questioned Davis’s political acumen, saying that his appeal lay with “swaggering braggarts and cunning poltroons.”

As a kind of consolation prize, Toombs was chosen as the Confederacy’s first Secretary of State. It was a job for which he was woefully unsuited. He was no diplomat, had in fact been overseas only once in his life for a quick tour of Europe, during which he’d judged each country by an unusual criterion: the quality of its cigars. After a few months, Toombs quit as Secretary of State, demanding a commission as a brigadier general in command of soldiers from his home state.

And here he was—the man who would be president of the Confederacy—commanding a tiny force of Georgians, trying to stave off a Union onslaught.

By All Means Necessary

By midday, Toombs’s Georgia boys were running low on ammo. Some had fired as many 60 shots, leaving their shoulders kicked black and blue. The artillery was tapped out, too. According to some accounts, the Rebels were reduced to firing “military curiosities” at this point, launching all manner of objects out of their cannons such as marbles and chunks of rail iron.

For the Federals, the slackening fire signaled opportunity. They began surging across the Antietam en masse, crowding onto the Rohrbach Bridge, fording the creek in other spots. The Georgians were flushed from their bluff-side hiding spots, and began retreating up a steep three-quarter-mile hillside toward the town of Sharpsburg.

But they’d achieved their objective and more: delaying the Federal crossing by roughly three critical hours. As a parting shot, some of the Georgia boys turned to throw stones and hurl insults at the oncoming Federals— these were Toombs’ men to the last.

Once the Federals had finally crossed Antietam Creek on this part of the field, the battle entered its most consequential phase. If Union forces managed to climb that hillside, they might cut off the ability of Lee’s army to re-cross the Potomac to the safety of Virginia. The Confederacy could lose the war this very afternoon.

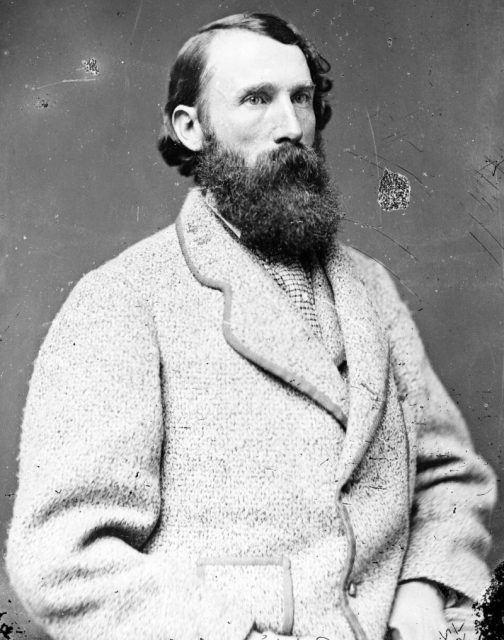

Retaking His Bridge

Famously, A.P. Hill arrived just in time, having marched 2,500 soldiers at breakneck pace from Harpers Ferry, 17 miles distant. The Rebel newcomers fell upon the advancing Union troops, driving them away from Sharpsburg and back down the steep slope toward Antietam Creek. Hill would be celebrated as the savior of the Confederacy. But Toombs also deserves credit, though his contributions have been mostly forgotten.

As Hill’s counterattack built, Toombs joined in the effort. His Georgia boys, the ones that had held the Rohrbach Bridge for so many hours, were too exhausted to fight. Instead, the general assembled a kind of spit-and-glue force with fresh soldiers from several other Georgia regiments.

As Toombs surged downhill, sweeping the Federals ahead of him, he joined forces with various wayward and shattered commands, soon assembling a formidable line. To the men, Toombs seemed nearly possessed. He leapt from his mare, Gray Alice, and ran to the head of the line.

There, the mad-maned, fire-eating old secessionist strode to and fro, spitting words and gesticulating wildly. He said he wanted to drive the Federals into the Antietam. He urged the men to retake his bridge—his bridge, he called it.

As the sun sank on the horizon, a lurid red disk, both sides were overcome by attrition and exhaustion. The soldiers under the command of Hill and Toombs halted. They started trudging back up the slope towards Sharpsburg.

Greatly relieved, the Federals simply held their ground. The bloodiest day in American history ended with a whimper not a bang. But Union forces had managed to fight to the far side of Antietam Creek.

The Rohrbach Bridge would come to be known as the Burnside Bridge in honor of the gingerly general who commanded the Union IX Corps. But for the slimmest of margins—a few more fresh soldiers, a push of a few hundred more yards—it really might have been his bridge, the Toombs Bridge.

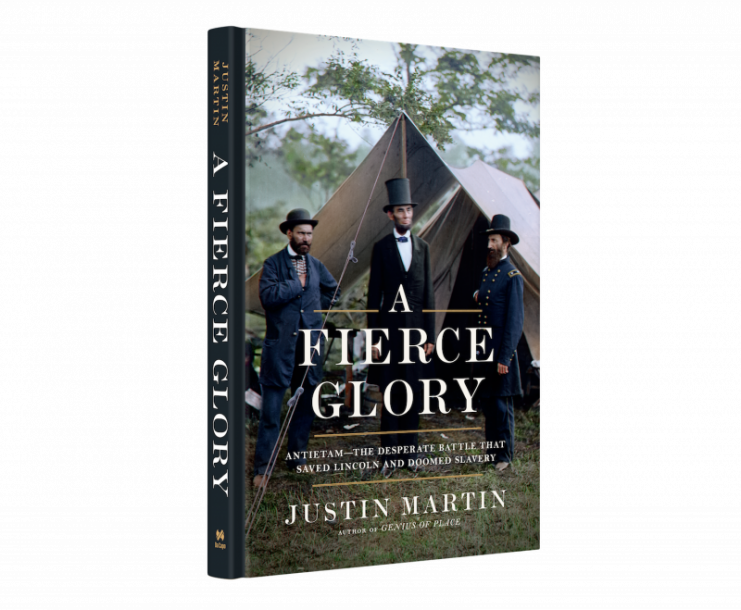

This is one in a series of posts, as guest blogger Justin Martin counts down to the September 17 anniversary of Antietam, still America’s bloodiest day. Martin’s posts will feature little-known episodes he learned about while researching his new book, A Fierce Glory: Antietam—The Desperate Battle That Saved Lincoln and Doomed Slavery (Da Capo Press).

You can order the book here.

Read another article from us – 1st Texas at Antietam – 80% Losses and Their Unique Flag

Justin Martin will continue to share some special and insightful stories about the Battle of Antietam throughout the week. Please stop by tomorrow to catch the next installment.