Hood led his brigade in a fast and aggressive attack that broke through the Union center, throwing the entire Northern army into disarray.

On the surface, the Texas Brigade did not seem destined for greatness in the American Civil War. Texas was one of the least populated states in the Confederacy, the most distant from major battles, and its soldiers were incredibly underequipped.

However, the men from Texas defied the odds and played a significant role in nearly every battle of the Eastern theater of the war. Despite their humble beginnings, they ended up becoming one of the most elite and highly regarded units in the entire Confederacy.

The Texans Arrive

When the Texas Brigade first formed it seemed destined for failure. The men showed up with whatever weapons they had at home, which led to a unit with wielding muskets from the 1830s, shotguns, hunting rifles, and pistols. Some of them did not have weapons at all.

However, the Confederacy held Texans in high regard. Texans had become legendary for their independence war against Mexico (which became the Mexican-American War), and well publicized battles like the one at the Alamo.

The Confederacy was also hopeful that slave-owning Western territories like New Mexico Territory would follow suit (and indeed, part of New Mexico seceded and became the Confederate Territory of Arizona). As a result, the Confederate government made sure the Texans got more modern equipment, in particular the Enfield Pattern 1853 rifle.

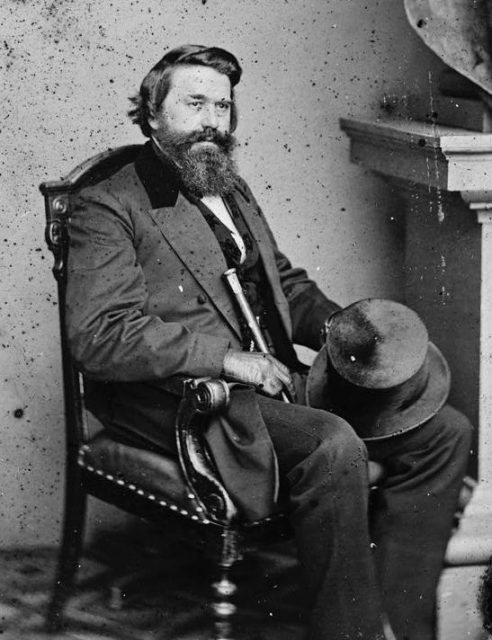

Like many units, the Texas Brigade was at first commanded by the man who organized it, in this case Colonel Louis T. Wigfall. However, Wigfall resigned the command in early 1862, and General John Bell Hood took command.

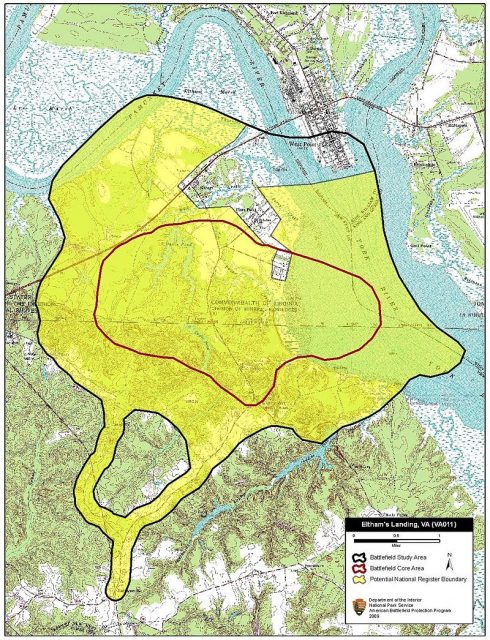

Hood’s Brigade would first see action at the Battle of Eltham’s Landing. Although Eltham’s Landing was only a minor engagement during the Peninsula Campaign, it was there that the Texans began to build their legend.

Building a Legend

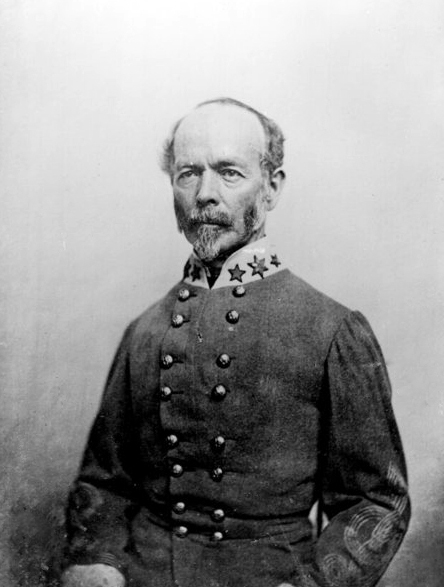

At Eltham’s Landing, Hood’s men fought side-by-side with the also legendary Hampton’s Legion. General Joseph E. Johnston, in charge of Confederate forces during the battle, ordered the Texans to “to feel the enemy gently and fall back.” In response, the Texans advanced upon the Union lines and drove them from the field.

After the battle a bemused Longstreet is said to have asked “What would your Texans have done, sir, if I had ordered them to charge and drive back the enemy?” to which Hood responded, “I suppose, General, they would have driven them into the river, and tried to swim out and capture the gunboats.”

Hood led his men into battle directly, and was nearly killed as a result. At one point he ordered his men to advance with unloaded weapons, since he feared that they would accidentally fire upon retreating Confederate skirmishers.

Instead, they stumbled upon a Union line. A Union corporal raised his weapon to fire directly at Hood, but one of the Texans had disobeyed orders and kept his gun loaded. That man killed the Union corporal before he could fire.

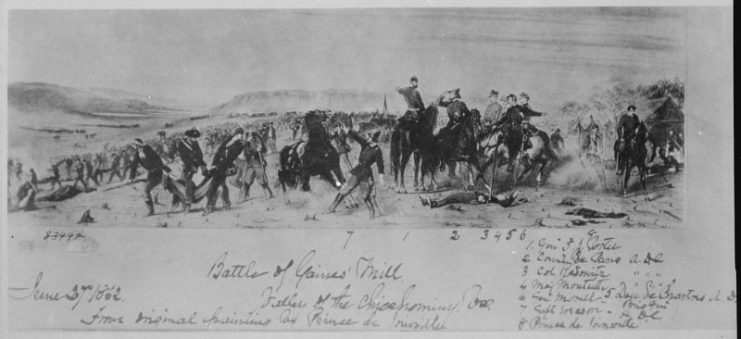

The Texans next saw significant action during the Seven Days Battles, particularly at Gaines’ Mill. As the sun was setting on the battlefield, the Union lines seemed to have held against the Confederate assault. However, General Longstreet wanted to try one more attack before the day was over.

Hood led his brigade in a fast and aggressive attack that broke through the Union center, throwing the entire Northern army into disarray. The U.S. 5th Cavalry attempted a counter-attack to prevent the Yankee lines from totally collapsing, but the Texans held firm, capturing many of the cavalrymen and inflicting heavy casualties.

Although the victory at Gains’ Mill came at a high price for the Texas Brigade—around 25% of them were casualties—their legend was cemented.

In the Thick of the War

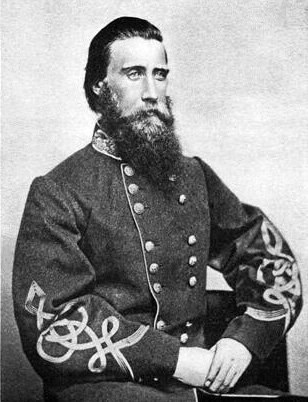

For most of the war Hood’s Texas Brigade would continue to fight under Robert E. Lee in the Army of Northern Virginia, and in particular with Longstreet’s First Corps. In late July 1862, Hood gained command of an entire division, including the Texas Brigade.

The brigade next saw significant action at Second Manassas, where they led Longstreet’s crucial attack on Pope’s left flank on the last day of the battle. They overran both the 5th and 10th New York Zouaves, inflicting around 300 casualties on the 500-man 5th New York Zouaves over the course of ten minutes.

Finally, they captured a battery and several key positions throughout the battle. However, the Texas Brigade suffered nearly 700 casualties over the three days of battle, leaving them severely depleted for the even larger battle that was to come.

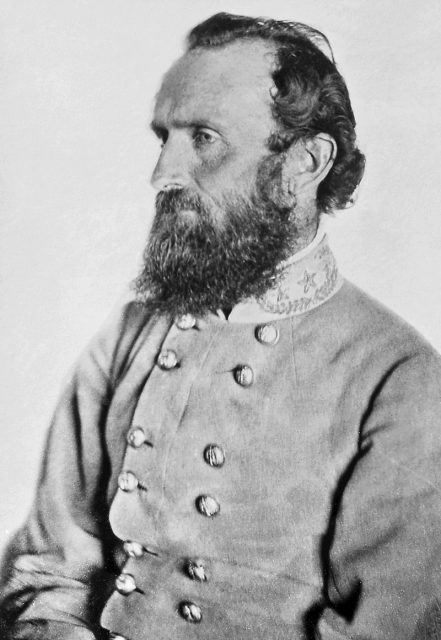

The Battle of Sharpsburg (Antietam) was the bloodiest single-day battle of the war. General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson’s corps was engaged in some of the fiercest fighting, centered around an infamous cornfield that changed hands over half a dozen times throughout the battle.

Hood’s men became engaged in the battle around 7:00 AM, filling a crucial gap in Jackson’s line and forcing the Union troops back across the cornfield. The Texans bore the brunt of Union counter-attacks, facing off against the legendary Iron Brigade and two corps. They suffered incredible casualties in the process.

At the end of the day Robert E. Lee asked Hood where his men were, to which he infamously replied “dead on the field.” The Texas Brigade had suffered around 60% casualties.

One of the Brigade’s proudest moments came during the Battle of Gettysburg when Hood and his men were chosen to taken the difficult terrain at Devil’s Den. Hood himself was wounded early in the assault when a shell exploded near him, injuring his left arm.

Although Hood would never regain use of his arm, his men took Devil’s Den after intense fighting and severe casualties. However, the Texans finally met their match when they were forced back after attacking Little Round Top.

Late War and Legacy

After Hood recovered, he and his brigade were transferred to the West, where they fought at Chickamauga. The Texans played a crucial role yet again by leading Longstreet’s assault against a gap in the Union line.

Although this was a turning point in the battle that led to the Confederate victory, Hood received another severe injury and had to have his right leg amputated. Although Hood would return to battle, this was the last time he directly led the brigade. However, they kept the nickname “Hood’s Brigade.”

The brigade took part in the sieges of Chattanooga and Knoxville, but returned to Virginia in February 1864. Under the command of General John Gregg the Texas Brigade arrived just in time to prevent the Confederate forces from breaking at the Wilderness.

Robert E. Lee was so happy to see their arrival that he rode up to them and began to personally lead their advance. However, the Texans objected, grabbing the reins to his horse and telling him that the risk was too great. Lee eventually relented at Longstreet’s behest.

By the surrender at Appomattox, the Texas Brigade had become one of the most legendary units in the Confederate Army. Out of 4,400 men, only around 600 remained to surrender with Robert E. Lee.

Read another story from us: Robert E. Lee. & The US Camel Corps That Never Were

Rightfully remembered alongside the Stonewall Brigade and Hampton’s Legion, the Texas Brigade formed one of the elite units of the Confederate Army and played crucial roles in many major battles.

Including some battles where they were held in reserve, they took part in nearly every conflict in the Eastern theater. For a brigade that started the war without even having enough guns for all of its men, the Texans performed better than they had any reason to.