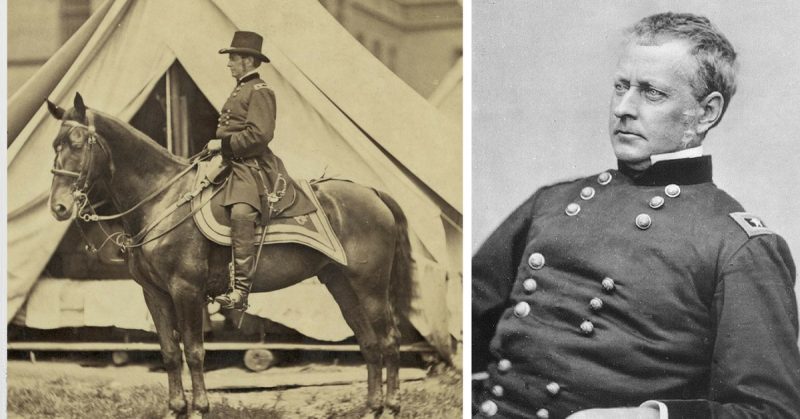

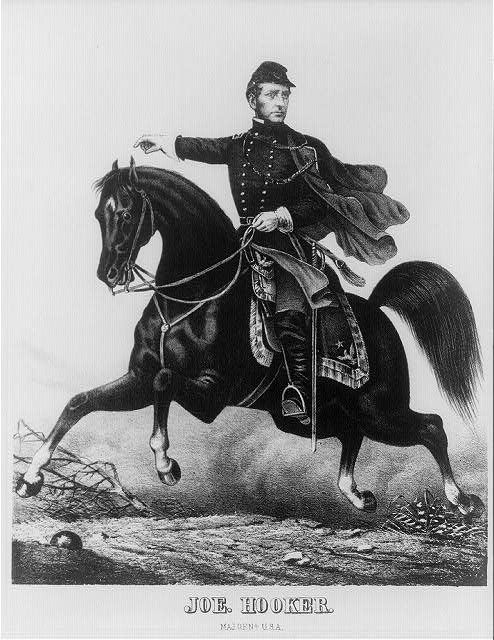

During the early days of the American Civil War, appointments of Union generals were as much about politics as skill and experience. The case of Fighting Joe Hooker is a prime example. After eight years outside the military, he returned as a general, puffed up with a sense of his own potential.

How did such a man come to be a general?

Early Experience

Hooker attended West Point Military Academy, as did many officers on both sides of the Civil War. Graduating in 1837, he emerged alongside officers such as Jubal Early and John Sedgwick.

Hooker served as an artillery lieutenant against the rebellious Seminole Indians. He then served on the Canadian border and as an adjutant at West Point.

When war broke out with Mexico in 1846, Hooker made sure he was part of the campaign. He served on the staff of several commanders, gaining experience of military administration and leadership. At the storming of Chapultepec, he proved his courage and dynamism as he played an active part in the assault. Although the Mexican campaign was successful for him, it also had a downside. His testimony in a court-martial alienated his former commander, General Winfield Scott.

Hooker remained in the military for several years after Mexico, but his ambitions were unfulfilled. Instead, he tried a civilian life in California.

California Volunteers

The outbreak of the Civil War created a golden opportunity for ambitious men like Hooker. Large forces were being raised, and officers were needed to command them. With many US commanders fighting for the Confederacy, the Union’s need for men with experience and energy grew.

Hooker gathered a unit of local volunteers ready to fight for the Union. Using his military experience, he began drilling them ready for war.

It was obvious from the start that the most important campaigns of the war would be fought in the east, where most of America’s government and industry were based. That was where Hooker aimed to be. He was therefore disappointed to learn that California regiments were not going to be accepted to fight in the east.

Hooker wrote to General Scott, the commander of the United States Army, offering his services. As an experienced soldier and leader, Hooker believed he would be an invaluable asset for the army. Scott, still stinging from the court-martial, did not respond.

Chapman’s Gift

It was a frustrating time for Hooker. He had good connections among California’s politicians, as well as relationships with officers he had served with. He assumed that, if he was in Washington, he could make use of those contacts to get the sort of position he wanted. However, he was short of funds, as was often the case, and could not afford to take the trip.

The despondent Hooker went into a bar run by his friend, Billy Chapman. There, he told the barman about his woes.

In a moment of dramatic cliché, Chapman responded with an act of incredible generosity. He was unwilling to serve as a private but lacked the experience or connections to become an officer. As a way of contributing to the war effort, he offered to pay for Hooker’s journey east. When Hooker advised he would need $700 for expenses and to clear his debts, Chapman provided him with $1,000.

Hooker was heading east.

Rather than resent his departure, Hooker’s unit wrote him a touching letter of thanks for his service. They offered to throw him a dinner, but he declined. Instead, he hurried to catch the first steamer to Washington.

Unsuccessful Petitions

On arrival in Washington, Hooker petitioned men of influence to give him a command. He contacted the friendly Senator Nesmith of California, Senator Baker of New York, and the congressmen from his native Massachusetts. He dropped off his credentials at the White House.

Washington was in chaos. Politicians were scrambling to fill positions with both career soldiers and volunteers such as Hooker. He saw his peers raised swiftly to high command and assumed he was worthy of the same treatment. When Governor Andrew of Massachusetts offered him a position as colonel of a regiment, he turned it down. He thought he ought to have a higher posting.

A letter from President Lincoln, listing Hooker’s credentials, reached General Scott. Hooker’s ambitions again hit a wall. Scott, still resentful of the court-martial testimony against him years before, set the letter aside.

He was not giving Hooker any favors.

Meeting Lincoln

Without a military position, Hooker was among the crowds who watched the First Battle of Bull Run on July 21, 1861. There he saw the Union Army soundly beaten. The situation was discouraging.

A few days later, he met with George Cadwallader, on whose staff he had served in Mexico. Together they went to the White House and he was introduced to Abraham Lincoln.

As Lincoln was turning away, Hooker spoke up. He talked confidently about his skills and experience and the good he could bring to the Union armies. Impressed with Hooker’s self-confidence, the President invited him to sit and talk. They exchanged stories, at the end of which Lincoln said to Hooker “I have a use for you and a regiment for you to command.”

The Brigadier List

On further investigation, Lincoln learned that Hooker’s political friends were pushing for him to have a higher position than a regimental commander. On July 31, Hooker’s name appeared fifth on a list of eleven men presented to the Senate. They were nominees for the post of brigadier general in the United States Volunteers.

On August 3, Hooker’s nomination was confirmed. At last, the government regarded his skills as highly as he did. He was finally going to war.

Source:

Walter H. Hebert (1944), Fighting Joe Hooker