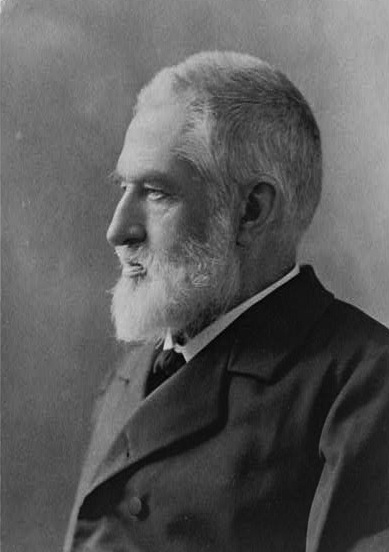

Jedediah Hotchkiss’s migration to the Shenandoah Valley in 1847 at age 19 proved to be more fortuitous than he could imagine. His long exploratory treks through the Valley kindled his interest in mapmaking. Although at first the pursuit was a side business to supplement his income as a schoolteacher and geologist, it became the defining work of his life and career.

The Valley Campaign of 1862

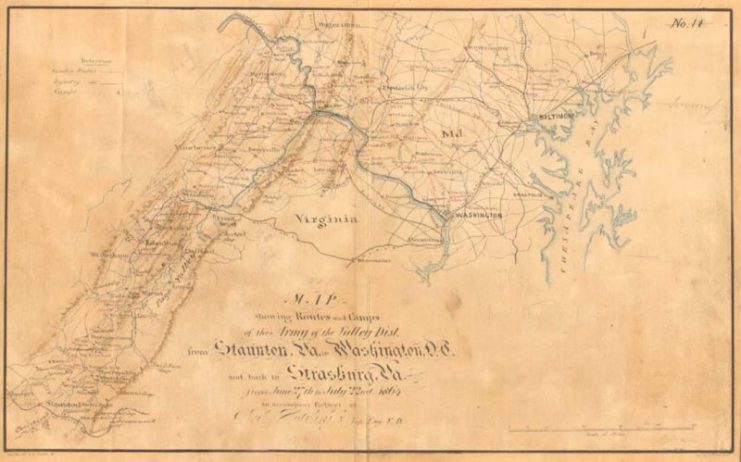

At the outbreak of the Civil War, Hotchkiss offered his mapmaking services to Confederate Brig. Gen. Richard B. Garnett and soon was drawing maps for Gen. Robert E. Lee. By 1862, Hotchkiss was assigned to the staff of Maj. Gen. Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson as chief topographical engineer. Jackson tasked Hotchkiss with a daunting assignment – mapping the entire 150-mile length of the Shenandoah Valley.

Hotchkiss’s thorough knowledge of the terrain as well as his skill at drawing accurate, detailed maps made him the perfect candidate for the job. The map became his masterpiece. He frequently revised and updated it throughout the war.

Hotchkiss became an invaluable member of Jackson’s staff. He was able to provide Jackson with vital intelligence about the terrain – the precise location of rivers, bridges, roads and mountain passes – allowing the general to plan his bold operations in the Valley.

Hotchkiss did much of his work on horseback, often riding as far as 35 miles a day, making careful notes and sketches using a compass and altimeter to take precise topographical measurements. He then worked long hours back at camp to create maps from his extensive field notes. His notebook had several small pockets on the front to hold the different colored pencils he used to distinguish various features.

At times, Jackson entrusted Hotchkiss to lead troops into position. Hotchkiss would also signal Jackson information about enemy movements from the top of Massanutten Mountain, the central mountain that dominated the Valley. If Hotchkiss spotted Federal forces in a vulnerable position he quickly pointed out little-known roads for Jackson’s advancing troops to travel.

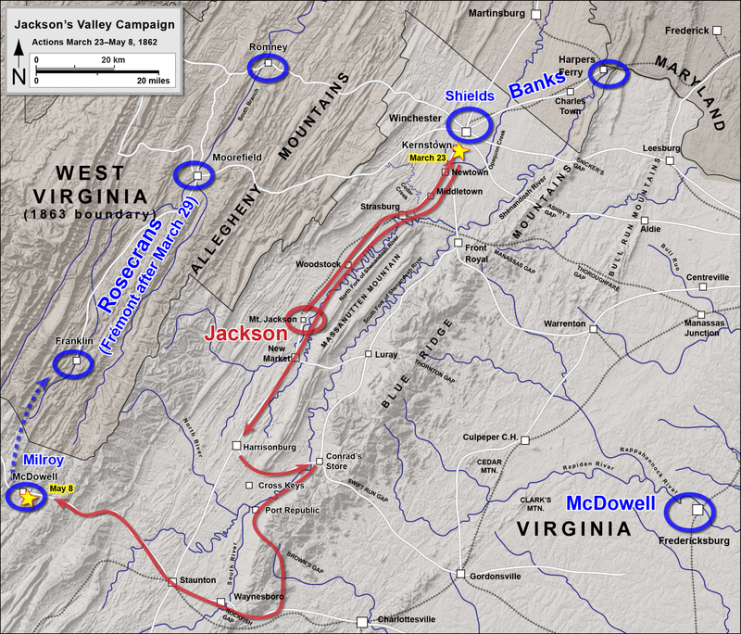

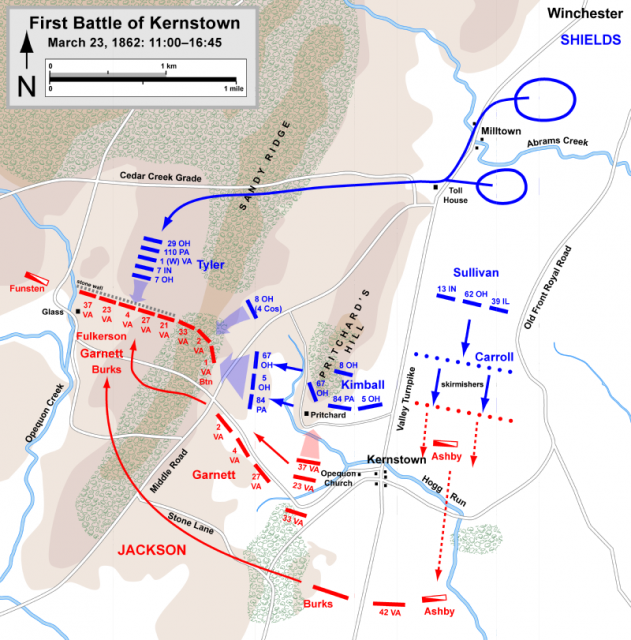

Jackson’s 1862 Valley Campaign was a legendary achievement. The small Confederate force outmaneuvered much larger Federal forces under generals William Banks, John C. Fremont and Irvin McDowell, diverting much-needed troop strength from the Union’s primary objective, the march on Richmond.

Triumph and Tragedy at Chancellorsville

Hotchkiss accompanied Jackson to Second Bull Run and Antietam. In 1863 Hotchkiss mapped the route that Jackson’s army took to surprise Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker’s Union forces at Chancellorsville. The resounding success of the Confederate flanking movement led to the Rebels’ greatest victory of the war.

But the triumph was marred by tragedy. While riding back from the front lines on May 2nd, Jackson was mortally wounded by gunfire from a North Carolina regiment that mistook his party for enemy troops. Hotchkiss was riding behind the general and rushed to find a doctor. Jackson died eight days later.

Hotchkiss was then assigned to Lt. Gen. Richard Ewell, Jackson’s successor as commander of 2nd Corps. He accompanied Ewell to Gettysburg in 1863 and was assigned to Lt. Gen. Jubal Early during the 1864 Valley Campaign, the South’s last invasion of the North.

In a reprise of his great contribution at Chancellorsville, Hotchkiss created a map that Early used to surprise the Union army at Cedar Creek in October of 1864. Although the brilliant maneuver routed two Federal corps, a Union counterattack later in the day annihilated Early’s army.

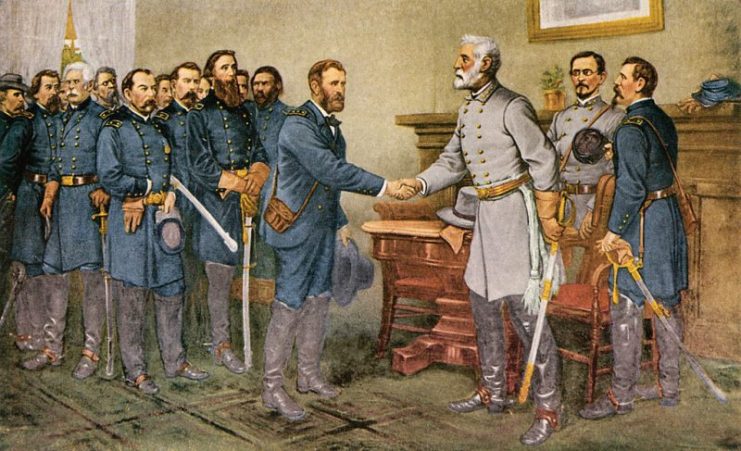

Hotchkiss was in Lynchburg when he received word of the Confederate surrender at Appomattox Court House in April of 1865. He turned himself in to Union forces and was paroled at Staunton. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant allowed him to keep his maps. Hotchkiss later supplied many of the Confederate Civil War maps that appear in The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies.

Post-War Recognition

After the war, Hotchkiss returned to teaching for several years and subsequently made a living as a surveyor, lecturer, cartographer and geologist. He became an expert on mineral resources in Virginia and West Virginia. He exhibited 96 Virginia mineral specimens at the New Orleans World’s Fair in 1885, as well as ten of his maps.

Read another story from us: Things We Didn’t Know About the American Civil War

Former Confederate colleagues who were penning their memoirs frequently consulted Hotchkiss and included his maps in their books. He contributed to the 12-volume set Confederate Military History, co-wrote The Battlefields of Virginia: Chancellorsville with William Allen, another member of Stonewall Jackson’s staff; and edited the quarterly publication The Virginias, a Mining, Industrial and Scientific Journal.

The Hotchkiss collection of 600 maps is housed at the Library of Congress in Washington, D. C.