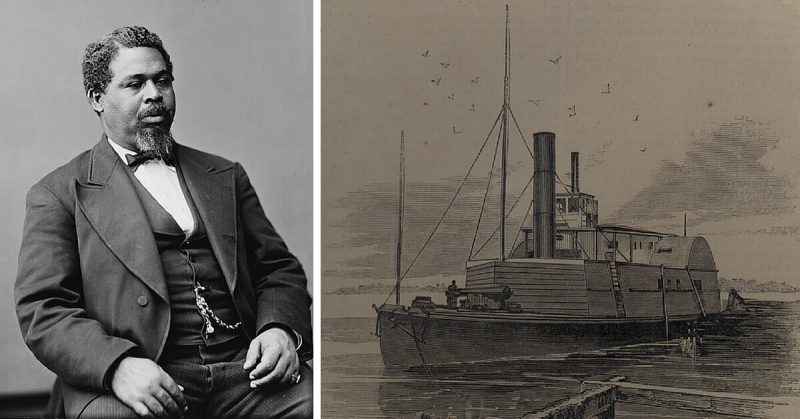

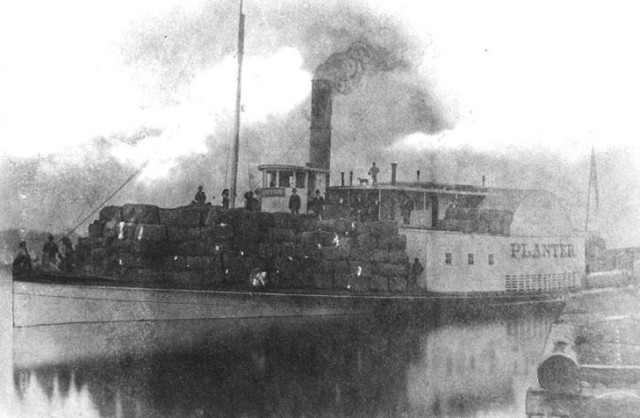

In 1862, Robert Smalls stole a Confederate ship, gave it to the Union Army, freed slaves, and met President Abraham Lincoln. After the war, he bought a townhouse and became a Republican politician – a remarkable feat for a slave.

Smalls was born on 5 April 1839 in Beaufort, South Carolina to Lydia Polite. The McKee family had bought Polite from a plantation when she was 9 years old to be a companion for their children. It’s believed that Henry, one of the older McKee sons, may have fathered Smalls.

Whatever the case, Polite worked as a housekeeper and had a small house at the back of the McKee property where she raised her son. Because of her position, Smalls was allowed to associate with white children and enjoyed freedoms usually forbidden to black people (both slaves and free).

An example of this was his frequent violation of the town’s curfew. Past 7 PM, no black people were allowed in public, but Smalls often ignored this as he played with white children. He was jailed several times but was always bailed out by Henry.

Afraid that he didn’t understand his situation, Polite asked her master to rent Smalls out when he was 12. The idea was to teach him how to behave, as a black man in white society, for his own protection. To achieve this, she sent him to Charleston where he was allowed to keep $1 of his wages while the rest went to his master.

Since it wasn’t enough, Smalls started buying and selling candy and tobacco. From there, he moved on to working in a hotel where he met Hannah Jones, another slave five years his senior. With permission from their masters, the two married when Smalls was 18 and were allowed to live together in Charleston.

Jones already had a daughter, but she and Smalls had another child, Elizabeth Lydia Smalls, who was born in 1858. Three years later, they had a son who died when he was two. Though a close family, their existence was precarious; they could all have been sold at any time.

Smalls became a lamplighter, a dock worker, a rigger, and a sailmaker before finally being allowed to pilot ships. Since black people couldn’t be captains, he was called a “wheelman” and allowed to sail all over Charleston Harbor. With his increased wages, he tried to buy his family’s freedom, but their combined price of $800 was too much.

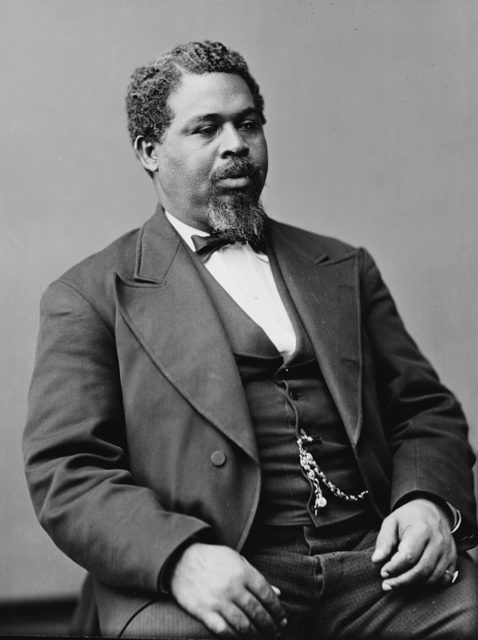

By 1861, Smalls was the wheelman for the Planter – a private sidewheel steamship which transported cotton. Then the American Civil War broke out on April 12th, so the Confederacy seized the ship for state use, renamed it the CSS Planter, and kept Smalls as their wheelman.

On 13th May 1862, Smalls took his place in history. The white crew were ashore. He was alone with the eight other slaves on board. They had been planning to escape for some time and seized their chance at around 3 AM. Smalls dressed up in the captain’s uniform, put on a straw hat like the captain did, and steamed out of the Southern Wharf to a nearby location to pick up his family and other slaves.

The party steamed down the Cooper River with the Confederate flag, but they weren’t safe. Five forts guarded the waterway, but in the darkness, none of the guards could see the color of his skin – only his uniform and hat. Fortunately, he knew the steam signal codes to give as he passed each one, so no one challenged him.

They passed the last one, Fort Sumter, at about 4:30 AM. Once past Sumter’s cannon range, Smalls took down the Confederate flag and hoisted a white blanket as he headed directly to the US Fleet, which had blockaded the port. The USS Onward spotted the Planter first and was about to fire when they saw the white sheet.

The crewmembers of the Onward were shocked. That a group of black men could pull off such a thing was beyond them. Acting Volunteer Lieutenant J. Frederick Nickels hopped aboard the Planter and accepted Smalls’ defection. To his delight, not only did the Union receive a new steamship, but it also acquired extra weapons and artillery. Best of all, the Planter had code books and a map of mines set around the Charleston Harbor.

News quickly spread throughout the North. Congress signed a bill granting Small and his men the cost of the steamship – renamed the USS Planter. Smalls’ share was $1,500 ($35,555 in 2016 values). He even met President Lincoln, who asked him why a black man would dare such a thing. Smalls replied with only one word, “Freedom.”

But it wasn’t enough. Lincoln didn’t want African-Americans in the Union Army, but Small convinced him (and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton) otherwise. The result was the 1st and 2nd South Carolina Regiment (Colored), made up of 5,000 African-Americans under the command of white generals.

Smalls was not allowed to join the Colored Regiments, however. The Union needed him for their Navy. He became the pilot of the USS Keokuk, which had been damaged during the failed attack on Fort Sumter in April 1863. So Smalls was transferred to the Planter where he again made his impact on history.

On December 1st of that year, the Keokuk got into a skirmish with the Confederate Navy. The captain wanted to surrender, but Smalls knew that he and the other black crew would face execution. To avoid that, he assumed command and got the ship to safety. For his bravery, he was made the captain of the Planter — the first African-American to hold that title.

After the war, Smalls returned to Beaufort, bought his former master’s house, and moved his family and mother into it. Jane Bond McKee, his former master’s widow was allowed to live there till she died. In 1865, he became a Republican and was voted to the South Carolina House of Representatives. He became a senator in 1871 and a member of the US Congress in 1884.

Smalls’ final appointment was as US Collector of Customs in Beaufort from 1889 till 1911. He died on 23 February 1915 – still the owner of the house where he grew up as a slave.