One of the greatest commanders of the American Civil War, Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson was also one of the most difficult to work with. Fierce, secretive, and driven by his fiery Christian faith, he put the fear of God into his soldiers and colleagues as well as his Union foes.

Training for War

Born in 1824 and raised by his uncle, Jackson had little regular schooling. He overcame this to gain a place at the military training academy at West Point in 1842. A hard worker, he excelled in the institute’s disciplined and rigorous training. He did so well that, on graduating, he had the choice of what arm of the military to join. Jackson chose the artillery.

Jackson, the Teacher

Jackson’s first military experience came in a campaign in Mexico. There he earned the rank of major for his performance commanding artillery.

Then he was posted to New York and Florida, where he clashed with fellow officers. Deeply religious and uncompromising, Jackson’s sense of right and wrong led to repeated conflicts.

In 1851, he became a teacher at the Virginia Military Institute, specializing in artillery. Again, he struggled to deal with the people around him. He could not maintain discipline in his classes and became miserable at his ill treatment by students.

Signing Up for a War He Did Not Want

As war loomed in 1861, Jackson opposed both secession and the violence it would trigger. As a loyal Virginian, he agreed to serve the Confederacy. Initially sent to Richmond to train soldiers, he was made a colonel and given an active command. He led a brigade of Virginians who would become known as the Stonewall Brigade.

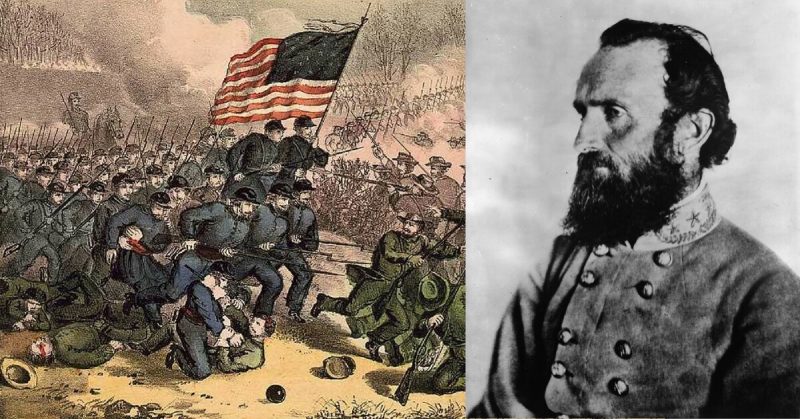

First Bull Run

In July, Jackson made his name at the first battle of the war. Known as Manassas Junction in the Confederacy and Bull Run in the Union, it was a messy affair.

As Confederate troops began to retreat in the face of Union attacks, Jackson and his brigade stood firm. General Bee, trying to rally his soldiers, said: “There is Jackson, standing like a stone wall.” Jackson’s example rallied the Confederate troops, and the Union army was driven back. His clear understanding of how to best use firepower allowed him to counter the enemy charge successfully.

Jackson had shown himself as a skilled leader and unflappable under fire. He drew the attention of General Lee and earned himself the nickname “Stonewall.”

The Valley Campaign

Lee gave Jackson the job of occupying Federal troops in the Shenandoah Valley. For the best part of a year, Jackson used his abilities to harass and baffle Union armies repeatedly. In a series of battles, he defeated four armies, took 4,000 prisoners, seized vast amounts of supplies, and inflicted thousands of casualties. All achieved with only 1,000 Confederate casualties.

The Road to Richmond

In June 1862, Lee recalled Jackson and his troops toward Richmond. Conflicting orders from Lee and secrecy from Jackson contributed to a series of bloody battles in which the Confederacy took heavy losses. In August at Cedar Run, Jackson’s intervention saved his men from a disaster caused in part by his own secretive leadership.

Second Bull Run

At the end of August, there was a second great clash at Bull Run. This time, Jackson’s troops held a heavily entrenched ridge. Again, they were faced with determined Federal assaults. Again, they held fast in the face of danger. A maneuver on the flank took the pressure off Jackson and drove the Union army off.

Harper’s Ferry and Sharpsburg

The following month saw two more Confederate victories.

At Harper’s Ferry, Jackson made use of his artillery experience. With carefully placed guns, he launched a bombardment that forced the surrender of 12,000 Union troops and all the supplies they guarded. There were only 100 Confederate casualties.

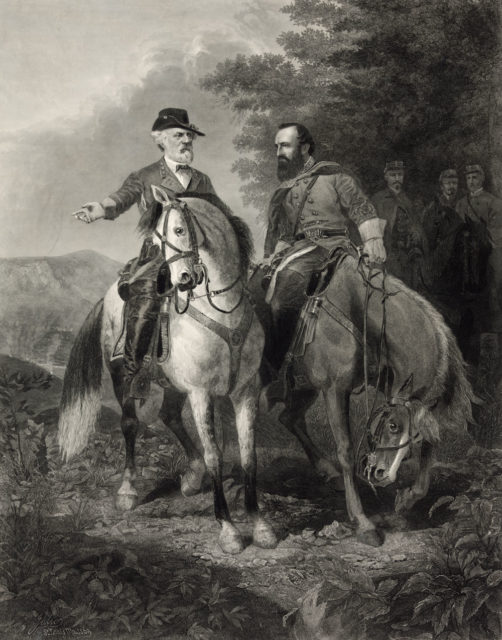

He then joined Lee for the fight at Sharpsburg. There, McClennan used skillful artillery tactics against the Confederates, but the failure of command on the Union side created opportunities for Jackson. The Union attack was broken. Lee and Jackson celebrated a victory against a much greater force.

Fredericksburg

The final battle of the Union drive to take Richmond came at Fredericksburg. Again, Jackson joined Lee’s army in a defensive battle.

Jackson commanded the Confederate right in positions behind a river. They came under attack from one of two major Federal advances. The Union troops made it across the river and began to turn Jackson’s right flank. Seeing the danger, he launched a strong counter-attack. Under heavy artillery fire, the enemy was driven back across the river.

Jackson’s counter-attack inflicted 5,000 casualties on the enemy. It also came at a terrible cost in the lives of his own men. The fighting around Richmond had been brutal, but ultimately his side won, and the Union withdrew.

Chancellorsville

After a winter lull, the battle began again.

In early May, Jackson moved to outflank Union troops near Chancellorsville. It was one of his most successful swift, deceptive maneuvers which marked his tactical style. The Union army was outflanked and caught by surprise. Charging in at close range, his troops quickly routed the enemy facing them.

Chancellorsville became another decisive victory for Lee, but it also included a terrible loss of lives.

Jackson was accidentally shot by his own men. His arm was amputated in an attempt to save his life. It failed, and he died on May 10.

A Man of Fervent Faith

Jackson was a brilliant strategist and a brave commander who always led from near the front.

He was also deeply flawed. The faith that gave him such courage made him an uncompromising disciplinarian and confrontational colleague. His obsession with secrecy meant his subordinates were often ill-informed. In his absence, they did not know what his intentions were.

He was one of the best commanders in American history. If not for his flaws, he might have been the greatest.

Source:

David Rooney (1999), Military Mavericks: Extraordinary Men of Battle.