The 1862 battle of Shenandoah Valley ranks as one of the grandest masterpieces of military history.

The Shenandoah Valley situated in Virginia and bounded to the north by Blue Ridge and to the south by the Allegheny Mountains offered strategic shielding and transportation advantages to the Confederate forces, and with its fertile soil and farming communities, provided food for them during the American Civil War (which lasted from July 1861 to March 1865).

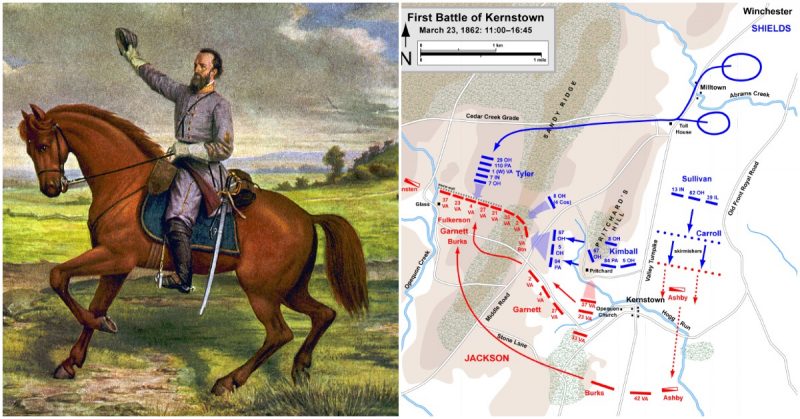

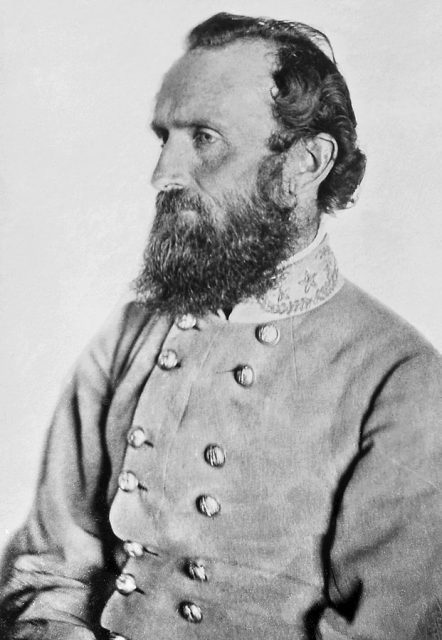

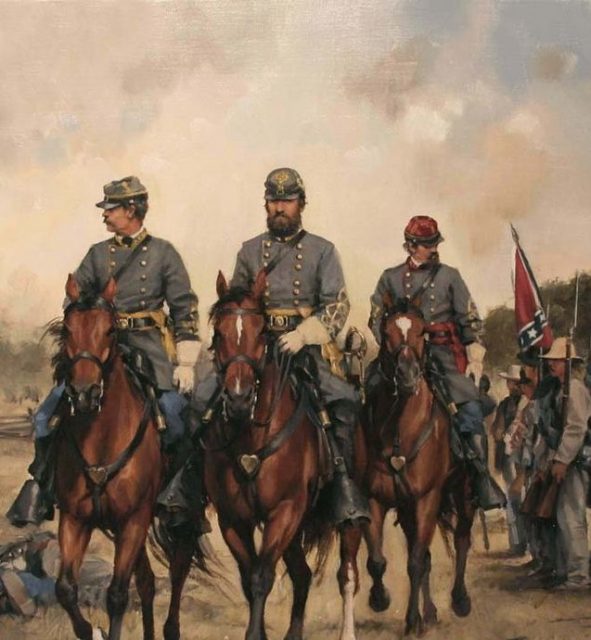

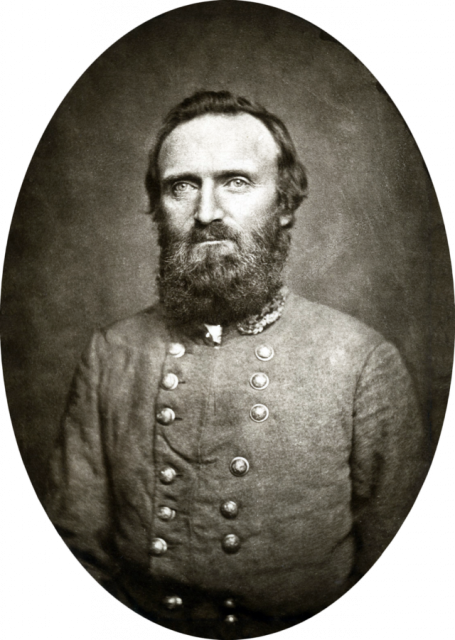

Not only is the Shenandoah Valley remembered for hosting dozens of intense, blood-spilling engagements between the hostile Confederate Forces who battled the intimidating Union Forces for control of the region, the campaigns at the Shenandoah Valley (alongside the events of First Manassas, or Bull Run) remains significant in Gen. Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson’s rise to fame.

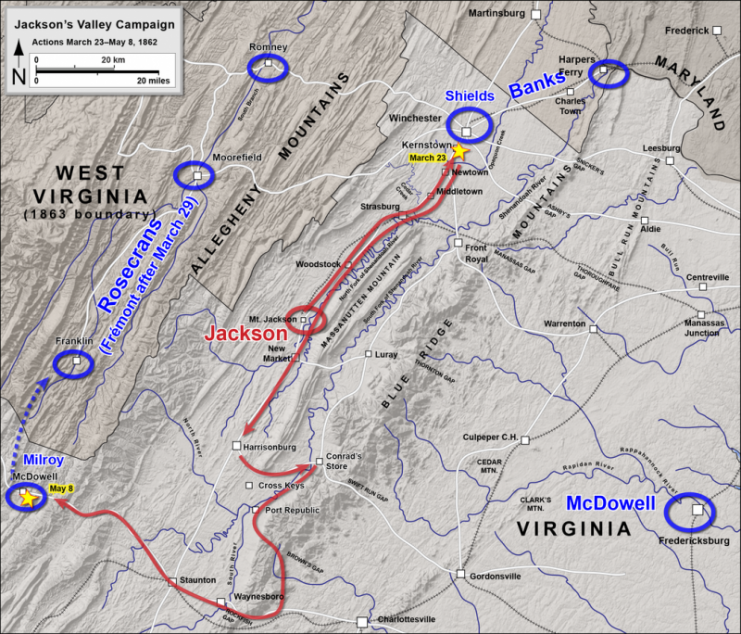

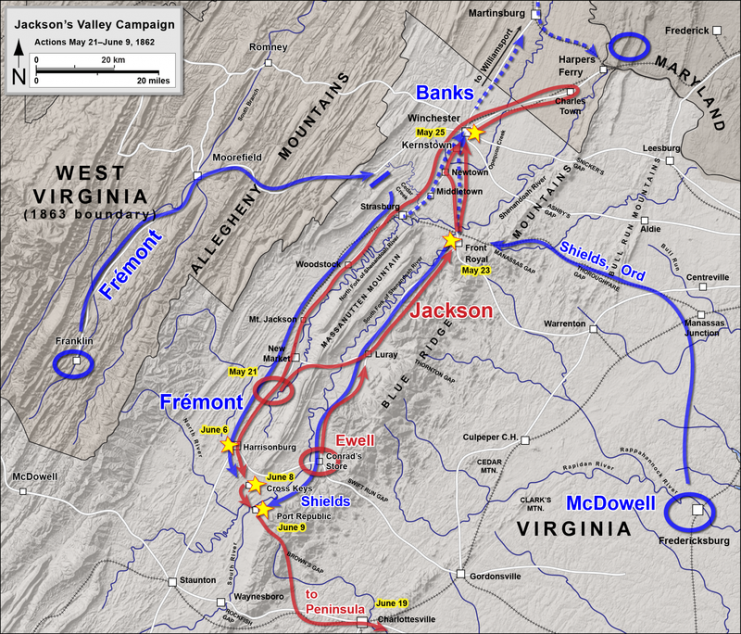

During the campaign of Shenandoah Valley, Jackson marched with a troop of 17,000 men across 650 miles in 48 days, in confrontation with about 40,000 Union Forces led by General Nathaniel P. Banks and General John C. Frémont.

His ‘foot cavalry’ fought five battles (The battles of McDowell, Front Royal, Winchester, Cross Keys, and Port Republic.), which resulted in a heavy depletion of Federal forces, threatened the fall of Washington D.C., and forced a retreat of the awe-struck Northern troops from the southern capital, saving her from capture.

Following the hostilities at First Manassas which turned out in favor of the Confederates, the odds turned against the confederate forces, stacking high against them as the Union forces moved with fierce determination, making significant progress in the battles of Fort Donelson and Shiloh in the Western Theater, and approaching Richmond (the southern capital) from both north and southeast.

The troops of General Nathaniel P. Banks were surging forth in a bid to take over the Shenandoah Valley; it is in the light of this that Stonewall Jackson wrote to a staff member saying, “If this valley is lost, Virginia is lost.”

While the battle seemed desperately unfavorable for the Confederates, Jackson who had taken command of Confederate troops in the valley, had an objective from Gen. Joseph E. Johnston: to protect the valley and prevent the Union troops from leaving.

This was key as part of the Union troops under Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks had been dispatched to join Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign against Richmond, while another part was sent to aid Maj. Gen. Irvin McDowell at Fredericksburg.

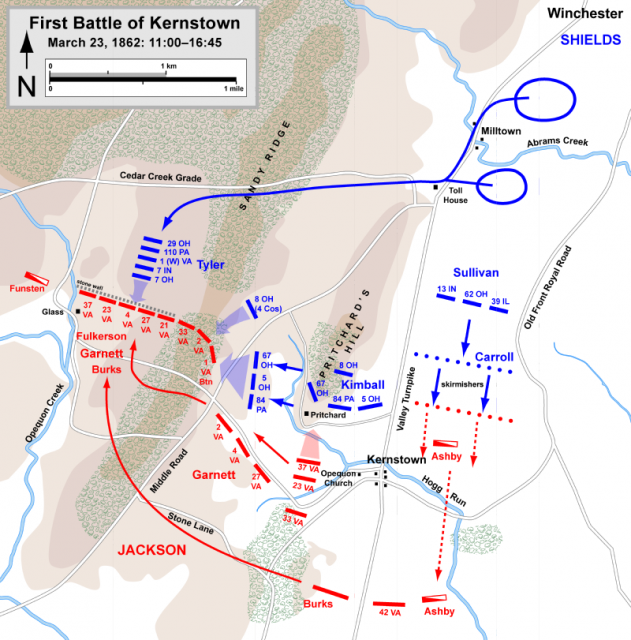

This had drastically shrunk Bank’s numerical strength, and seizing this opportunity, Jackson surged after them at Kernstown with his 4,600 men. Although they were still substantially outnumbered and suffered a technical defeat, Jackson’s troop struck Banks so hard that he had to recall some of his units that he had dispatched to McClellan and McDowell.

The battle of Kernstown produced about 590 casualties for the Union forces and about 718 casualties from the Confederates with most of those wounded or captured.

While the McClellan Peninsula campaign was well in progress, Joseph E Johnston sent most of his troops to aid in the protection of Richmond. However, he reinforced Jackson with 8500 men under the command of Maj. Gen. Richard S. Ewell with orders to prevent Banks from capturing Staunton, Virginia and the Tennessee Railroad.

Jackson had planned for Ewell to head on with his troops to Swift Run Gap to disorient Banks’ flank while he joined Brig. Gen. Edward “Allegheny” Johnson at Staunton. He wanted defend it against attack from Brig. Gen. Robert H. Milroy who was the leading figure in Maj. Gen. John C. Frémont’s forces.

This plan had been strictly to prevent Banks’ troops and Fremont’s troops from joining forces. Jackson was concerned that if this were to be allowed, the confederate’s troop would be overwhelmed.

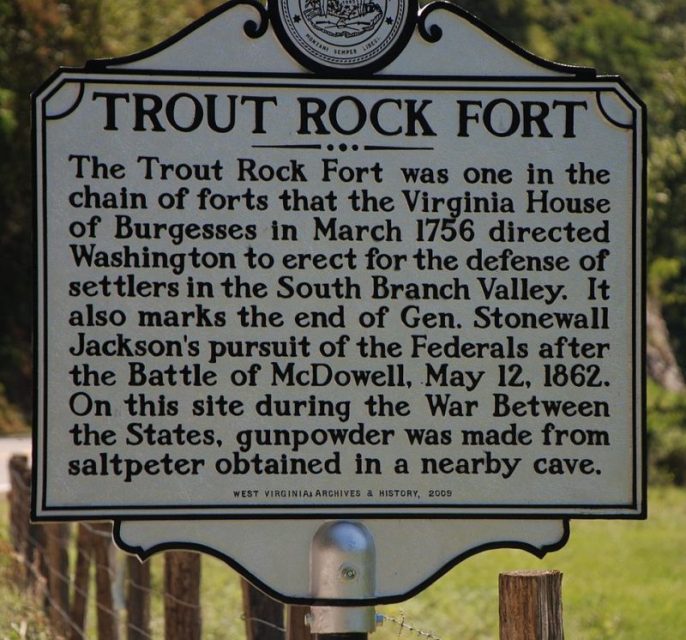

When Jackson joined Johnson at Staunton, Johnson’s army numbered about 2800 men, facing Fremont’s force of around 20000 men. However, with the aid of Jackson’s boisterous army, they overwhelmed Fremont’s army near McDowell, chasing them more than 30 miles up the South Branch Valley to Franklin.

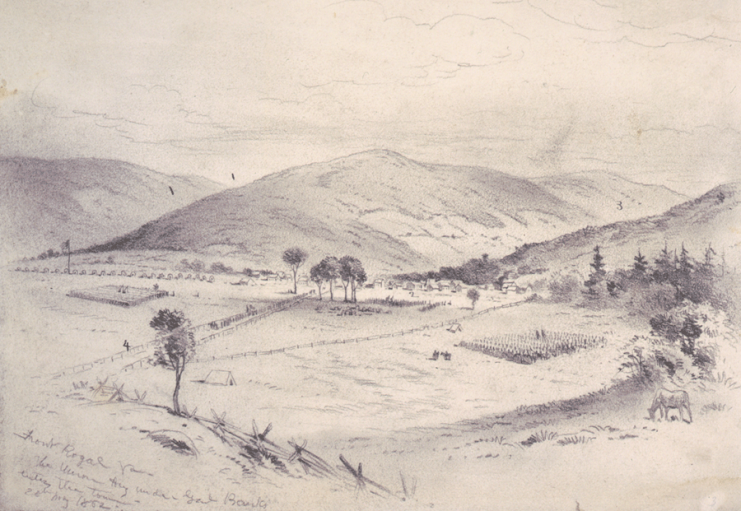

On May 22, Jackson rejoined Ewell, and then he sent General Ashby north to make Banks believe that there was an attack coming to Strasburg. But his first plan was to defeat the smaller Union detachment at Front Royal.

Ashby’s troops met a small force of Union infantry who briefly defended the Union depot and railroad base at Buckton Station. Ashby’s troops overpowered them, destroyed the depot and cut all telegraph wires available, eliminating Front Royal communication with Banks who was at Strasburg.

Jackson meanwhile was on his on journey towards Front Royal and eventually captured it. Union forces at Front Royal suffered about 773 casualties of which 691 were captured. The Confederates lost about 36 men in all and captured a huge amount of Federal supplies.

The event at Front Royal troubled President Lincoln enough to recall about 20000 men under Maj. Gen. Irvin McDowell from their initial move to join George B. McClellan on the Peninsula campaign.

Following the news of the loss at Front Royal, Banks ordered for his men to retreat to Winchester. This information got to Jackson who immediately gave the Federals a hot chase. The Union army raced about 35 miles in 14 hours, crossing the Potomac River eluding Jackson’s forces.

The escape is due largely because Ashby’s cavalry was not available when they were needed. In the end, this event resulted in about 2000 casualties from the Union forces and 400 casualties from Jackson’s.

News of Jackson’s exploits rang through to Washington where President Abraham Lincoln was concerned about the possibilities of the Jackson surging up to Washington. In response, Lincoln ordered that Fremont march from Franklin to Harrisonburg to engage Jackson to help remove the pressure being exerted on Banks from the enemy forces.

He also called off McDowell’s march to Richmond, ordering him to march to Shenandoah with 20000 men with the objective of capturing Jackson and Ewell’s forces. This drastic change of plan was intended to trap Jackson’s army using three Union armies from three different approaches.

Fremont would surge upon his supply line from Harrisonburg while Banks would move back across the Potomac and attack Jackson if he moved up the valley. McDowell’s troops would be poised at Front Royal lying in wait for Jackson’s fleeing troops and would crush them with Fremont at Harrisonburg.

Although the plan seemed sound, it required synchronous operations from the three different Union generals. Moreover, McDowell was not quite enthusiastic about his role, and instead of going as ordered, he sent the division of Brig. Gen. James Shields (which just came from Banks’ army). Fremont on his own part would ignore Lincoln’s directives and take the route north of Moorefield.

On May 30th, Shields succeeded in recapturing Front Royal, and Jackson’s army began heading to Winchester.

On June 2nd, Jackson’s army was on the run as the Union armies approached from various angles. General Ashby later died in an engagement with Fremont’s cavalry at Chestnut Ridge. Jackson’s men marched 40 miles in 36 hours and slipped by the Union Forces who were impeded by the rains and muddy roads.

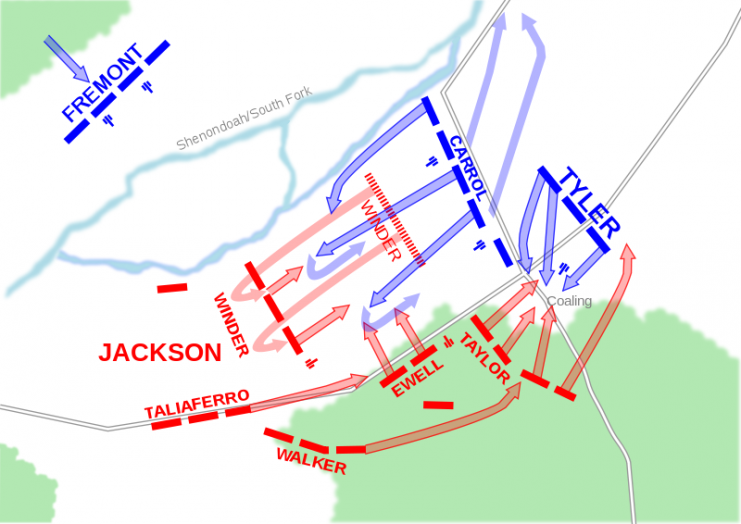

Chasing after Jackson separately was a big error on the Federal’s parts, and Jackson was quick to grab this opportunity. Jackson moved his troops across the North River bridge at Port Republic, where the North and South rivers joined to become the South Fork of the Shenandoah. He knew the small town of Port Republic was crucial and by destroying the bridge at the confluence, he would be able to keep Shield and Fremont apart.

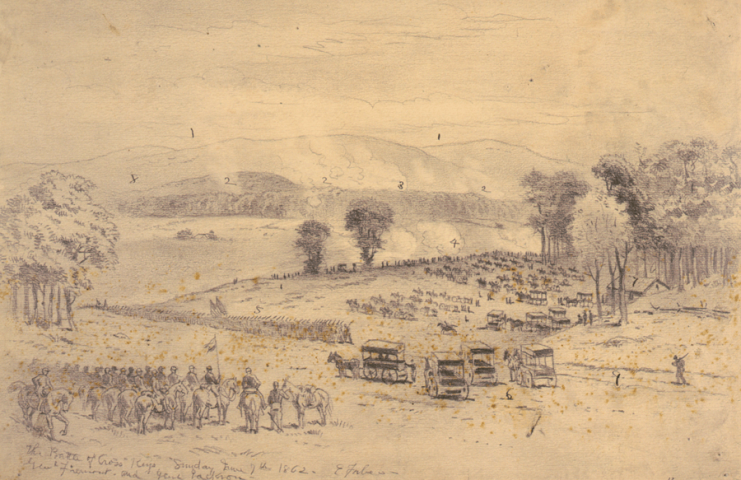

He set Ewell on his way to a ridge 7 miles from Cross Keys, to engage Fremont. On June 8th, Fremont marched to meet Ewell with a force of 11,500. Ewell’s troop numbered just 5800 after detaching Richard Taylor’s brigade to join Jackson.

Fremont struck first, but he had been mistaken about Ewell’s ‘strategic flank’. While he engaged the Confederates in heavy bombardments, he ordered 5 regiments under Brig. Gen. Julius Stahel to find Ewell’s flank, but in the course of executing his orders, Stahel was met by Confederate general Isaac R. Trimble’s brigade.

Trimble’s men sent fiery volley, raining down on Stahel’s men. This resulted in over 200 casualties as Stahel’s men retreated in haste. When Fremont received the news, he ordered his forces to retreat to Keezletown Road. Ewell and his troops pursued and recovered more ground, but they did not aggressively engage the retreating Union units.

Meanwhile, Jackson had been thoroughly engaged as Union horsemen surged unexpectedly into Port Republic wherein he made his headquarters. He narrowly escaped being captured while running down across the North River Bridge to join his units on the crest beyond. His men later reentered the city and sent the cavalry units back across the South River. The incident also announced the presence of Shield’s column.

Later in the day Brig. Gen. Erastus B. Tyler marched two brigades of Union infantry in a sunken lane that stretched across the fields between Lewiston and the South Fork. Here, Tyler mounted six cannons, ready to bring hell to the confederates.

Jackson, not intimidated by Tyler’s threats, ordered rig. Gen. Charles S. Winder across the South Fork with the Stonewall Brigade to attack Tyler’s line, but this was not successful.

Jackson ordered Ewell’s forces back to Port Republic, and they poured through the Southern River. Jackson also ordered Taylor’s Louisiana brigades to go through the woods and disrupt Winder’s attack.

Taylor went with his men, flanking Winder’s cannons. They captured the cannons from the rear, turning them against the Union. Simultaneously, Jackson’s forces surged forward from Port Republic, driving the Union forces on their heels once again.

The battle at Port Republic marked the end of Jackson’s 1862 campaign. He had marched against an enemy far greater in numbers and had consistently outmaneuvered them. Although the level of casualties in the campaign was much smaller compared to later campaigns, Jackson’s Valley Campaign was instrumental in securing Richmond’s protection.

Through these fierce battles, he had drawn the Northern troops away from Richmond, saving it from ultimate capture. With only a force of about 17000 men, he had proven that sometimes just when numbers seem to be beyond you, your determination to keep fighting is enough to turn the battle in your favor.