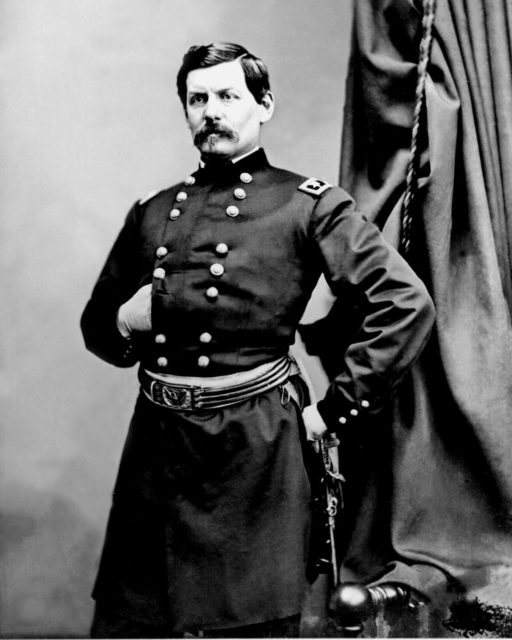

George McClellan’s reputation is not a good one. As commander of the Union armies early in the American Civil War, he is often credited as a significant factor in his opponents’ successes.

The irony is that McClellan’s weakness was grounded in his successes and the failures of other men.

McClellan’s Character

McClellan was not the worst choice of commanders. An efficient drillmaster and administrator he had achieved successes in the war’s first months. He turned the Army of the Potomac into a well-oiled fighting machine. His promotion to command of a critical army in the east and then to overall commander of the Union forces seemed a natural choice.

McClellan was both cautious and indecisive. Unwilling to take risks, he was no match for the men he faced such as bold commanders like Lee and Jackson. What turned the apparently successful general down his self-destructive path?

Pride

McClellan’s letters reveal a belief in his own greatness that seems at odds with the timidity shown in the campaign. Following his initial successes and promotions, he basked in the adulation of a public desperate for a hero. In letters, conversations, and newspaper articles he received the sincere praise of the northern public. He was even referred to as the Young Napoleon. It was a powerful comparison in an age when Napoleon and his followers dominated military theory. At West Point, the greatness of Napoleon was a given. McClellan’s education climaxed in coming second in his class, an achievement that could only add to his self-belief.

McClellan’s pride fuelled his ambitions. He contemplated the presidency and made an unsuccessful run against Lincoln in 1864.

It also limited his capacity to take criticism. Like anyone who believes themselves better than others, McClellan shut out opinions that contradicted his own. If he felt cautious, then he must be right to feel so. After all, he was the Young Napoleon.

A Fall

The sheen soon began to wear off McClellan’s reputation, revealing the dark side of being the center of attention. As he delayed and prevaricated, the government started to turn against him. Instead of leading the army into action against the Confederacy, he led it in grand reviews. It was not what they had hired him for. Their favor and support melted away.

Relations between McClellan and the people he worked for became increasingly toxic. His letters showed a man descending into self-pity, becoming ever more peevish and defensive in his attitude.

McClellan referred to the president as a “gorilla,” the Cabinet as “geese,” and the Secretary of War as a “depraved hypocrite and villain.” He was obsessed with the hurt others were doing to him and did not listen or find the courage for bold action.

Manassas Syndrome

As well as his own successes, McClellan’s behavior was shaped by the failure of his colleagues. McDowell’s loss to the Confederates at the First Battle of Bull Run cast a long shadow over the war.

The specifics of how McDowell lost the war’s first major battle were less important than the impression it created. On both sides of the conflict, many people bought into the myth that the Confederacy was militarily superior. The view flattered the egos of southerners and helped northerners to explain away their unexpected defeat. It boosted Confederate morale and shook that of the Union.

Historian James McPherson has referred to this attitude as “Manassas Syndrome,” after the southern name for the battle. McClellan had not been in the fight, but he arrived in Washington a few days after. There he saw the shaken remnants of the Union forces and was caught up in the hysteria around the defeat. Although his self-belief was absolute, his belief in Union forces was shaken by Manassas.

Inflating Intelligence

McClellan found ways to reinforce his beliefs. In his paranoia, he emerged with a perspective distorted far beyond reality. He inflated the estimates of Confederate numbers given to him. He frequently claimed his forces were outnumbered by the Confederates two to one or more when the reverse was true. At one point, his 100,000 troops were held up by 23,000 Confederates, while McClellan claimed the enemy was stronger.

He was supported by information received from Pinkerton’s Private Detective Agency. Many historians have argued that knowing McClellan’s belief in the weakness of his position, the Pinkertons gave him what he wanted – evidence to support his claim. Bias clearly played a part – humans are prone to taking in the information they agree with and disregarding other evidence.

It was a self-justifying view of the situation. As long as he could claim to be outnumbered, McClellan could excuse his inaction while maintaining his proud self-image. So he clung to that belief.

Fear of Failure

Those factors can be summed up in a simple phrase – fear of failure.

Before taking his position of high command, McClellan had never faced a significant failure. The challenge he faced was greater and the attention upon him more focused. If he fell, he would fall hard. By finding excuses not to fight, he avoided taking a risk and facing the possibility that he was as flawed as everybody else. Blaming others meant it was not his fault.

Inaction became McClellan’s failure. It was a raw wound, open for all the world to see. It held back the Union and ultimately led to his dismissal. All because he had once succeeded while others failed.

Sources:

James M. McPherson (1988), Battle Cry of Freedom: The American Civil War

James M. McPherson (1996), Drawn With the Sword: Reflections on the American Civil War

Geoffrey Regan (1991), The Guinness Book of Military Blunders