The Battle of Chancellorsville was one of the most important of the American Civil War. It saw one of the war’s bloodiest days of fighting, the ruin of General Hooker’s reputation, and the loss of General Lee’s right-hand man.

May God Have Mercy on General Lee

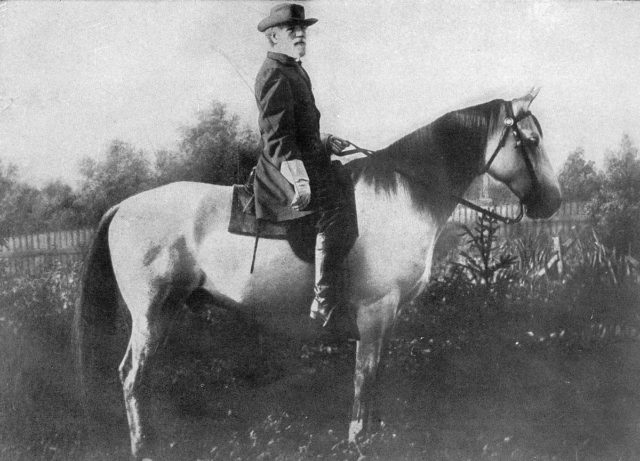

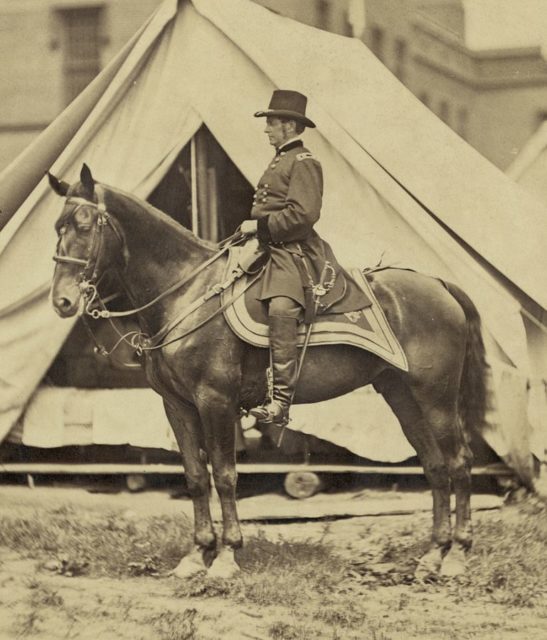

The Chancellorsville campaign began with high expectations in the north. Union General “Fighting” Joe Hooker had long promised a more aggressive approach to the war. Finally given command of Union armies in the East, he said of his opponent “May God have mercy on General Lee, for I will have none.”

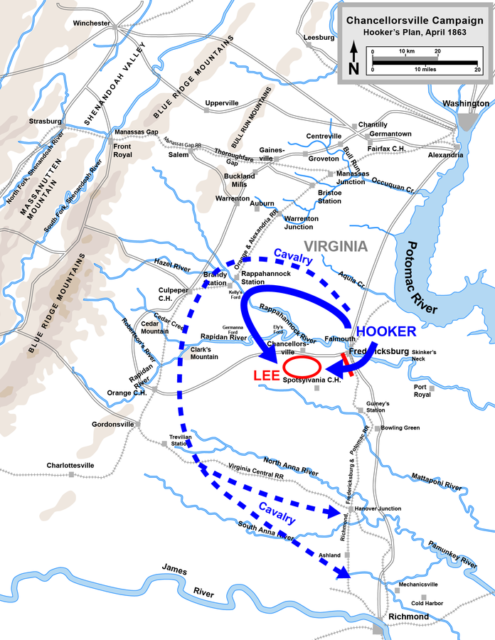

In a series of complicated maneuvers, he brought his army into position at Chancellorsville, near Fredericksburg. Outnumbering the Confederates there two to one, it was Hooker’s chance to triumph.

However, when they arrived on April 30, 1863, instead of attacking, Hooker waited for Lee to attack him.

First Clashes

Deciding to face Hooker, Lee marched most of his forces out of Fredericksburg and headed west. On May 1, his men clashed with Union forces a few miles east of Chancellorsville.

It was the perfect opportunity for Hooker. The open ground would have let him make use of his superior numbers and artillery, but he lost his nerve. He pulled his troops back to defensive positions in the dense woods around Chancellorsville.

The Flank March

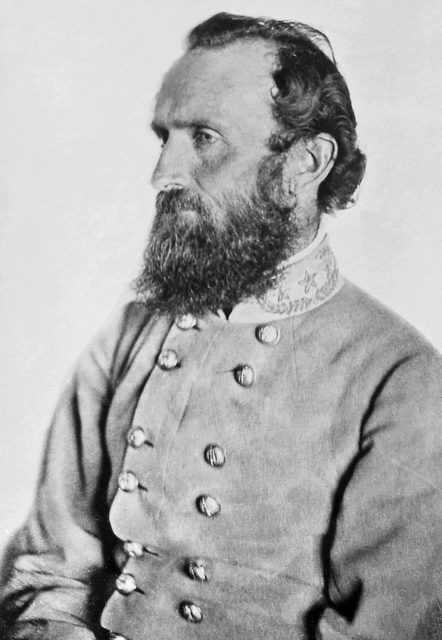

That night, Lee and his colleague Stonewall Jackson came up with a scheme to make use of Hooker’s failure. The next morning, Jackson headed out with two-thirds of Lee’s forces. Marching west, they took a twelve-mile route around Hooker to outflank the Union troops.

It was a huge gamble. Lee was left hugely outnumbered and would have been crushed if Hooker had attacked.

Still, Hooker waited.

The Attack

Assuming the Confederates would retreat and that the western woods were impenetrable, Hooker did not worry about reports of Confederate movement to the west.

It was a terrible mistake. Just after five in the afternoon, Jackson’s forces poured out of the woods. The Union units they encountered were relaxing and making supper. The Union right flank descended into chaos while Jackson drove them back through two miles of the wilderness woodlands.

(Apocryphal painting depicts the wounding of Confederate Lt. Gen. Stonewall Jackson on May 2, 1863).

Mistakes Under Moonlight

Fighting continued into the moonlit night. Hooker hurried to reposition his men and hold back Jackson’s advance. Lee joined his subordinate on the offensive, piling on the pressure. Sporadic and chaotic fighting marked one of the war’s few night engagements.

During the battle, Jackson rode out to reconnoiter the Union lines. As he returned, nervous Confederate soldiers shot him, believing he was an enemy. Two bullets hit his right arm, and it had to be amputated. He died of an infection eight days later.

Lee was winning, but he had lost his most valuable lieutenant.

Sedgwick Takes the Heights

The battle was split between two sites nine miles apart – the woods around Chancellorsville and the area around Fredericksburg. On May 3, Hooker finally made a fighting move. He ordered John Sedgwick to move the forces at Fredericksburg forward, seize the heights behind the town, and then attack Lee’s rear.

It was easier said than done. Twice, Sedgwick’s troops were driven back from the heights. At last, on the third attempt, they took the high ground in a bayonet charge.

Complacency and a Close Call

Meanwhile, Hooker remained cautious to the point of complacency. Instead of attacking with his superior numbers, he waited for Lee and Sedgwick to play their parts. It gave Lee the chance to reunite his forces near Chancellorsville and bring their weight to bear in an all-out attack.

Lee’s aggressive maneuvers created openings Hooker could have used to his advantage. Despite having three Union corps in reserve, he did not attack.

In mid-morning, a cannon shot hit the post next to where Hooker was standing at his headquarters. The post exploded, and he was knocked out. He soon recovered but just before another cannonball hit where he had been lying.

Withdrawal

Hooker’s swift recovery was, in many ways, a disappointment to his lieutenants. His already faltering nerves only worsened. He ordered the Union forces to withdraw north, forming a more compact defensive line.

By mutual consent, the armies around Chancellorsville ceased fighting. It gave them a chance to rescue injured men from the dense woodland, which was on fire due to exploding shells. Lee arrived at the mansion where Hooker had stood a few hours before, to huge cheers from his men.

The fighting continued near Fredericksburg, and Lee redirected many of his men there.

The Last Day’s Fighting

The next day, Lee led more of his troops east, to take on Sedgwick at Fredericksburg. It left his remaining men under Jeb Stuart outnumbered three to one. Lee was counting on Hooker remaining as passive as he had been so far.

The gamble paid off. Hooker still did not attack.

Confederate forces attacked a Union army of equal number on the heights outside Fredericksburg and were driven back. Sedgwick knew though that his commander had given up and there was no point in continuing the fight. That night, he pulled his troops out, retreating across the Rappahannock River.

Retreat

Most of Hooker’s commanders wanted to go on the attack. Half their forces had not fought, and they had superior numbers. Surely they could win.

Hooker had lost faith. As Lee planned another attack, the Union general withdrew. The battle was over.

It was a tremendous victory for Lee, but at a terrible cost. He had suffered 13,000 casualties to the Union’s 17,000, but that was 22% of his army. It was 15% of the Union forces. Most critically, he had lost Jackson.

Chancellorsville ended Hooker’s command of the Union forces and his nickname became ironic. For the Confederacy, it was a triumph, and proof of the fighting skill of Robert E. Lee.

Sources:

Walter H. Hebert (1944), Fighting Joe Hooker

James M. McPherson (1988), Battle Cry of Freedom: The American Civil War