Though leading an army of an estimated 12,000 soldiers, General Price believed the Union forces protecting Jefferson City to be too formidable.

At the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, 71-year-old Enoch Enloe Sr. had been living near the fledgling community of Russellville for three decades. One of the original pioneers of the area, he eventually set down roots on a farm on property that is now the Enloe Cemetery.

He would go on to demonstrate zeal and ambition by establishing the community’s first grist mill, running a blacksmith shop, stable, and hotel, and serving as the first postmaster for Russellville.

Enloe and his wife raised a large family despite losing several children at an early age. Records of Enloe Cemetery indicate that prior to the Civil War, he and his wife had already buried three young sons on his farm.

After the Civil War erupted, he had older sons who served with the Union army as part of the Enrolled Missouri Militia (EMM), which the State Historical Society of Missouri describes as a “state force” that was “primarily mobilized as needed.” Designated as protection for their home areas, members of the EMM were not issued uniforms and were encouraged to use their own weapons.

The elder Enloe, while working the farm and running his various business endeavors, heard accounts of guerilla activity in the area and later learned of the approach of a massive Confederate army. In an effort to protect both his family and property, he erected a location to conceal both his valuables and a firearm, the latter of which he could reach quickly if a threat emerged.

https://youtu.be/mYpNz7bvB1g

Near the gravesites of his sons, the hardy pioneer erected a raised limestone block that possesses all appearances of a burial spot. Under the bulky stone is an area that was dug out and where items could be concealed from view.

“One lady told me, when Great, Great Grandfather Enoch Enloe heard that Price’s army was coming he hid his old musket gun under a large flat grave rock,” wrote Reba Alexander Koester in her 1976 book The Heritage of Russellville in Cole County. She added, “At the time he hid the gun, the big rock was surrounded by a thick growth of tall blackberry bushes.”

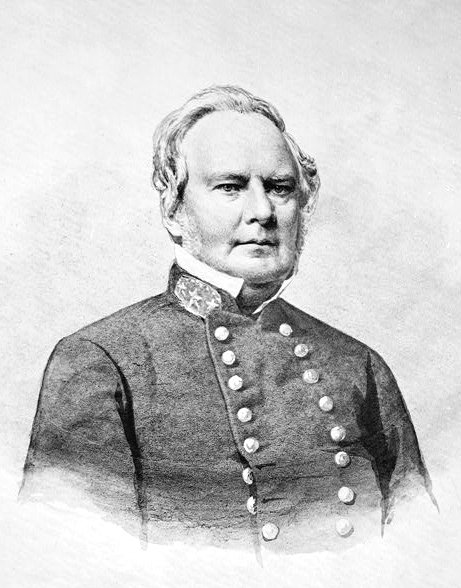

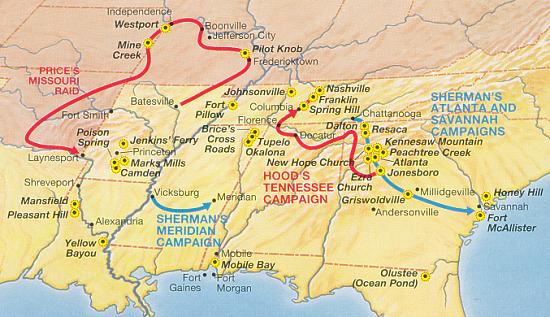

In The Civil War in Missouri Day by Day: 1861-1865, Carolyn Bartels explained that Confederate forces “burned the Osage Bridge on the river [near the present community of Taos] on October 6th (1864). After skirmishing near Bode Ferry, these troops, under the command of General ‘Jo’ Shelby, moved west toward Jefferson City to meet up with General Sterling Price, who intended on capturing Jefferson City.”

Though leading an army of an estimated 12,000 soldiers, General Price believed the Union forces protecting Jefferson City to be too formidable. Price then began a westward movement following the Old Versailles Road, much of which is now Route C. When passing near Lohman, his soldiers shot and killed two Bavarian immigrants—Erhardt Kautsch and Friedrich Strobel.

Price’s army was pursued by a mounted force organized by Union general John B. Sanborn. “On Sunday, October 9 [1864], Sanborn’s men covered another four miles and faced ‘lively skirmishing’ just two miles shy of Russellville,” wrote Mark A. Lause in his book The Collapse of Price’s Raid: The Beginning of the End in Civil War Missouri.

The skirmishing passed through the Russellville area and near where the Enloe Cemetery is now located. The fleeing Confederates were pursued throughout much of western Missouri until they were eventually confronted by Union forces in the Battle of Westport.

Local metal detectors Chris Heimsoth and Michael Kisling have tracked much of the route of Price’s Expedition through mid-Missouri. With the permission of the board of Enloe Cemetery, they detected open areas of the cemetery in an attempt to locate evidence of skirmishing—such as dropped coins, cannon balls, fired bullets, and uniform buckles and buttons.

No evidence was discovered, leaving the pair of amateur historians to speculate that the Confederate troops took a route a short distance to the south of the current cemetery location.

As noted in the “Russellville Sesquicentennial 150 years” published in 1988, the Enloe Cemetery was founded on October 16, 1866 when Enoch Enloe donated “two acres of land … to be used as a burial ground for his children, relatives and friends of the family.”

The musket Enloe hid under the stone remained in the family for a number of years and was passed down from one generation to the next, explained Ruby Koester in her aforementioned book. Nevertheless, in 1976, it was donated to the Cole County Historical Society “for safe keeping and so other Cole Countians could enjoy it.”

Norris Siebert of Russellville, a descendant of Enoch Enloe and longtime member of the Enloe Cemetery board, noted that although many have speculated whether someone is buried beneath the raised stone, his use of a dowsing rod—an ancient process used to locate certain buried objects—demonstrates there are no human remains buried there.

“Sharing tales of those we’ve lost is how we keep from really losing them,” wrote Mitch Albom in his novel For One More Day.

Read another story from us: ‘An Unknown Destination Overseas’

The decades after the Civil War saw grand monuments erected to honor those who gave their lives in the deadliest of all U.S. conflicts. In a cemetery near Russellville, however, exists a small limestone block that to this day serves as a story that continues to be shared in the community and is a link to the rough-hewn pioneer who built it.

Jeremy P. Ämick writes on behalf of the Silver Star Families of America.