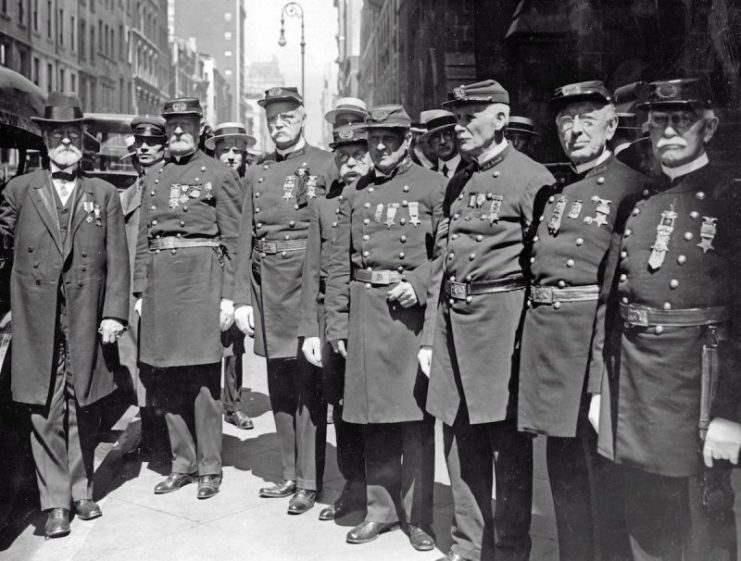

The American Civil War is today perceived as a hugely important part of the early history of the nation, with its witnesses and participants long gone. But the oral history of the war which has been passed down through generations still lives on with descendants of the soldiers who fought for both the North and the South.

“They’re a true link to another part of this country’s history. Whether Confederate or Union, they’re a treasure. The stories they tell today are the stories they heard as they sat on their daddy’s knee.”

These words, spoken by Gail Lowman Crosby for National Geographic, really illustrate the importance of those living today who still carry the stories from that time told to them by their fathers. Lowman Crosby is the president of the historical society United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC), who work to honor the memory of their ancestors.

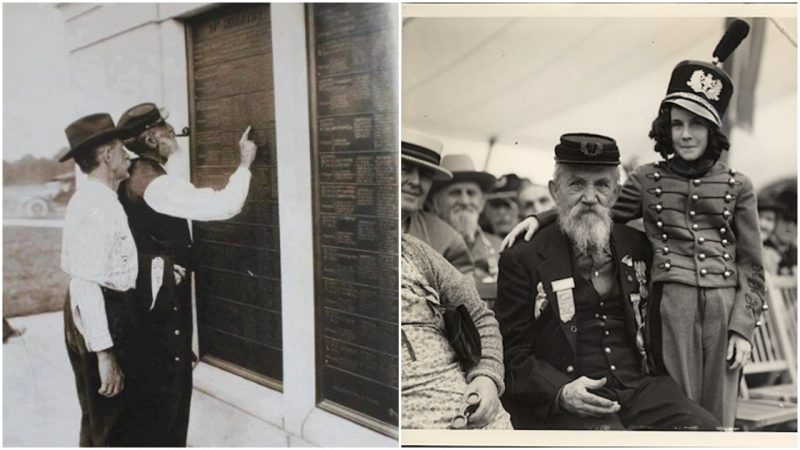

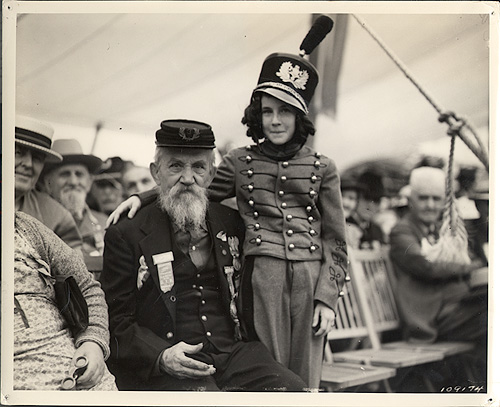

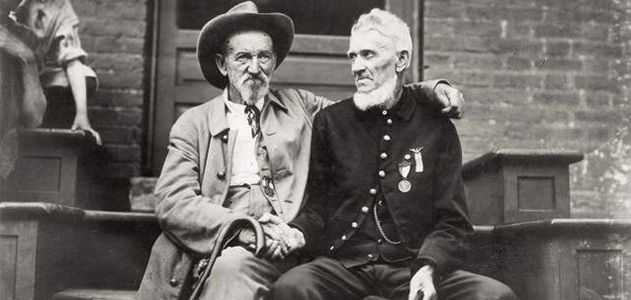

People like Fred Upham and Iris Lee Gay Jordan, who were among the sons and daughters of Civil War veterans whose fathers had fought for the Union and the Confederacy, respectively. Both of them have now passed away, but their legacy and the legacy of their fathers―William Upham and Lewis F. Gay ― lives on.

The National Geographic article from 2014 that featured Iris and Fred noted that the reason for this seemingly peculiar time anomaly was because their fathers were in their 70s when they were born but their mothers had been much younger. This was common practice at the time, especially when it came to veterans whose lives had been interrupted by war. Thus the children were in their early 90s when the interview took place.

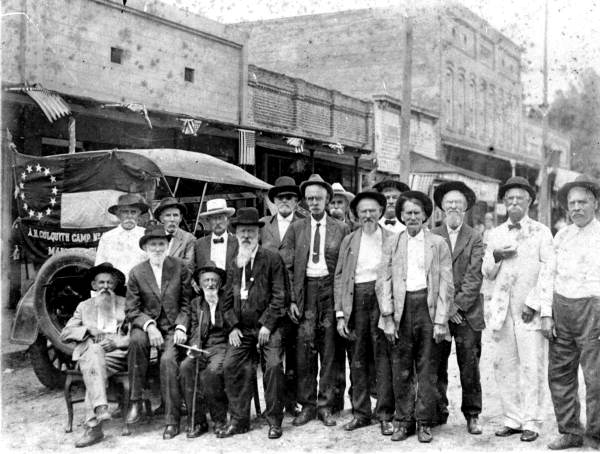

There were around 35 such “real sons” and 11 “real daughters” who had the privilege of hearing stories first-hand from the war, together with tales of the hardships and the ideas that went on to shape the United States of America.

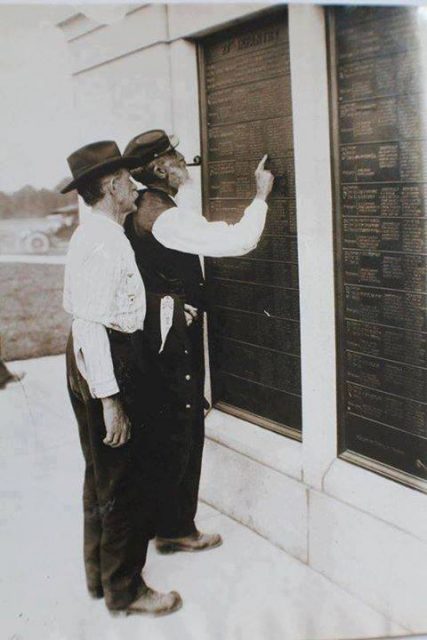

Fred’s father, William, was a volunteer and a private during the First Battle of Bull Run in 1861, where he was badly wounded and was later captured. He spent almost a year in Libby Prison, in Richmond, Virginia.

His counterpart in this story, Lewis Gay from the Confederation’s Fourth Florida Volunteer Infantry, was also captured during 1861 and was imprisoned in Fort Delaware, near Wilmington. Both were released after a prisoner swap sometime in 1862. The situation worsened as the war dragged on and such POW exchange agreements became very rare. They both testified how their treatment in captivity was dignified and humane, and that they held no personal grudges against their captors. Iris recalled her father telling her about the experience:

“My father said that the men in the North were just like he was. He told us: ‘We were all far away from home, and we all would much rather have been home with our families.’ There was no bitterness on his part at all.”

As for William Upham, his ordeals were heard by none other than President Abraham Lincoln, who expressed wishes to meet him. During the conversation, William was asked by the President to show his battle scars and to retell his experience as a prisoner of war. Afterward, Upham was sent to West Point Academy as a reward for his sacrifice.

Corporal Lewis Gay saw combat after his release and participated in many battles in Virginia, Tennessee, North Carolina, and Georgia. By the end of the war, he was one of the 23 surviving members of his regiment.

Others such as Clifford Hamm, the son of Confederate soldier John Hamm, pursued a career in the military. He recalled his father’s sentiment towards the defeat of the South:

“My father would never acknowledge the South was defeated. He used the word ‘overcome’.”

On the other hand, the sons and daughter of Charles Parker Pool ― John, Garland, and William, and Florence Wilson ― told of their father’s experience as a Union soldier in the Sixth West Virginia Infantry:

“My father didn’t like to talk much about the war” ― Garland told the National Geographic ― “He did say the main reason he wanted to fight was that he didn’t want to see the nation divided, and because he was against slavery.”

The oral histories that have been kept within the families of Civil War veterans are priceless today, more than 150 years after fighting ceased, as the memory of the conflict would otherwise fade away completely.