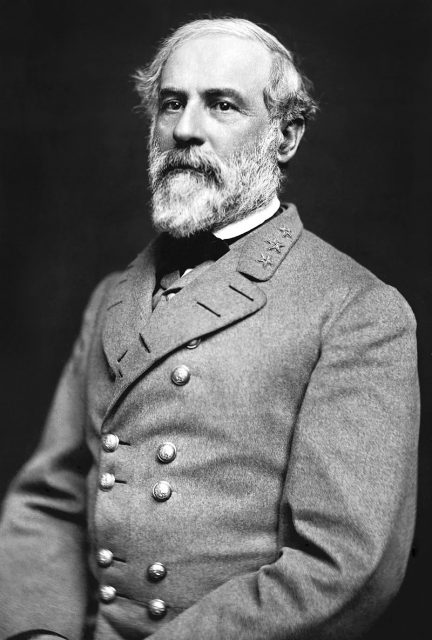

While Chancellorsville is often regarded as General Robert E. Lee’s greatest victory, many would be surprised to know that after the battle he remarked “We had really accomplished nothing; we had not gained a foot of ground, and I knew the enemy could easily replace the men he had lost. At Chancellorsville we gained another victory; our people were wild with delight—I, on the contrary, was more depressed.” He even went so far as to yell as his own generals and subordinates, accusing them of not obeying his orders and costing the South a true victory.

What could have led the general to such a conclusion? After all, the victory was widely celebrated in the South, and the North was sent into a panic at every level of leadership up to President Lincoln.

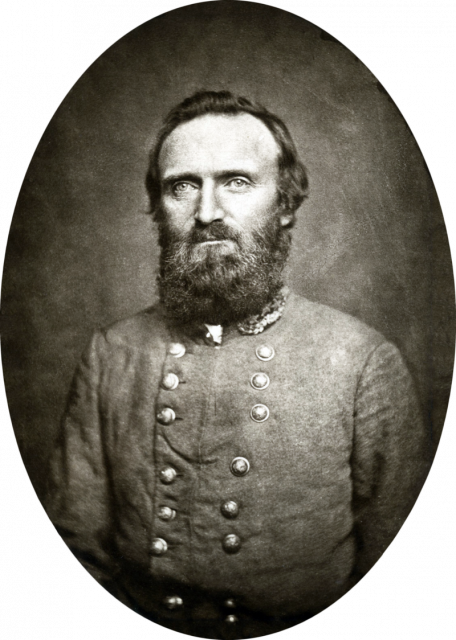

The loss of General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson is widely known, but Lee’s concerns went much deeper than the loss of his best general and friend – Lee realized that he had lost an opportunity to permanently cripple the Union army and potentially end the war.

Ever the perfectionist, this lost opportunity would haunt him for some time, and he made his frustrations known to his subordinates, some of whom had not acted in accordance with Lee’s orders. Did the Confederates have a realistic chance of ending the war, or at least dealing a much greater blow to the Union, at the Battle of Chancellorsville?

Throughout this conversation it is important recognize the manpower advantage the North had, and in particular their ability to replace their losses. Although the Union suffered around 17,000 casualties to the South’s 13,000, the Army of Northern Virginia lost over 20% of its soldiers in the battle, including nearly a third of its officers, while the Army of the Potomac only lost about 15% of its men. This is why Lee was not satisfied with merely driving the Union back – it was simply not sustainable.

The weapons the North lost could likewise be replaced with relative ease. Lincoln himself had made this observation after the similarly “disastrous” Union defeat at Fredericksburg, saying that if “the same battle were to be fought over again, every day, through a week of days, with the same relative results, the army under Lee would be wiped out to its last man.”

The only way the South could win would be with either such a great victory that the North would not be able to recover its numbers in time to stop a Confederate advance into the North, or by inflicting such losses that the Northern public would turn strongly against the war, thus making it politically unfeasible for Lincoln to continue fighting.

Lee recognized this, and decided that the political impacts of a greater victory would be worth the risks of an aggressive effort to rout and destroy the Army of the Potomac. The North would have to choose to give up due to the loss of blood and treasure the war extracted, rather than being defeated traditionally. In some ways Lee was already succeeding, as the Democratic platform by 1863 was already calling for an end to the war, even if it meant Southern independence.

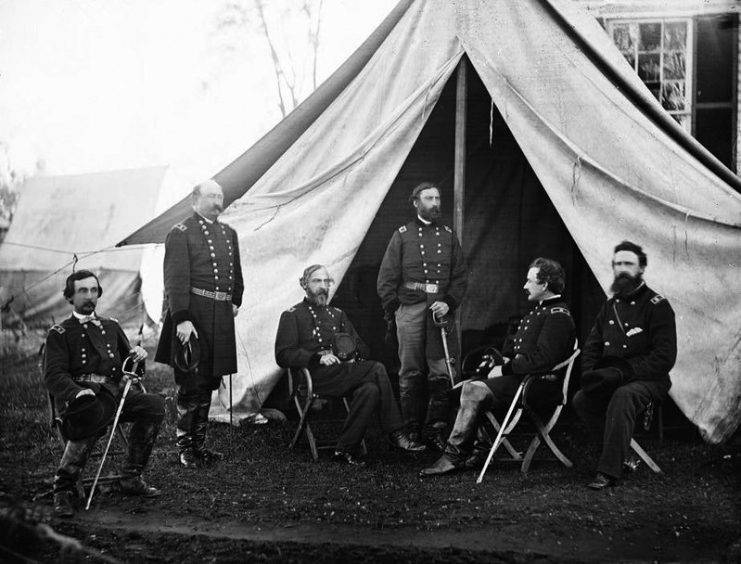

The Union retreat from Chancellorsville took place over several days, and involved two separate forces that needed to cross the Rappahannock River back to the North. Beginning late on May 3, 1863, Union forces began to withdraw in the face of Lee’s bold and successful decision to split his own forces repeatedly in the face of an opponent with superior numbers.

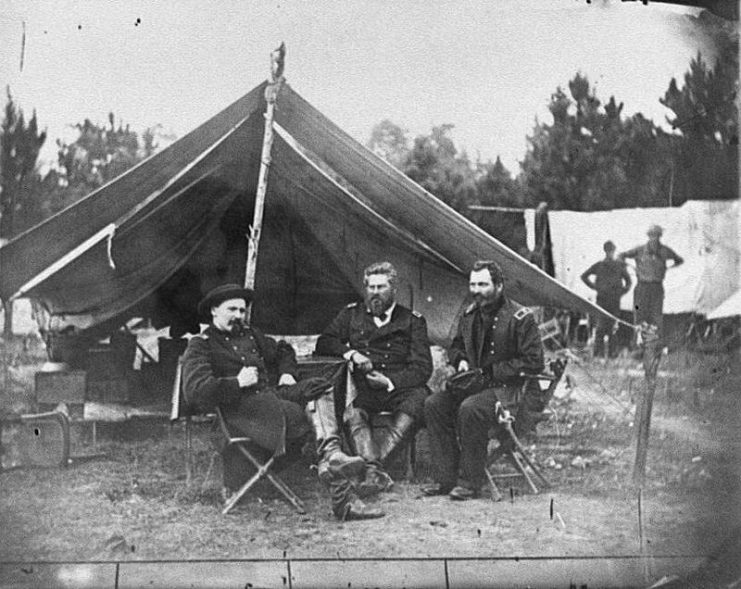

The Union forces had been split in two, with one section under the command of General Sedgwick, and the other under General Hooker directly. Lee wanted an attack on the morning of May 4 in order to press his advantage, but indecisive and slow actions by his subordinates led to the failure of this plan.

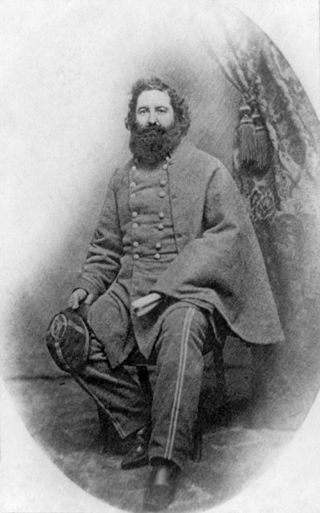

In particular, Confederate efforts against Sedgwick’s section of the army failed when General McLaws failed to join in an attack by General Early when ordered to because he felt his forces were not strong enough. Instead, McLaws delayed for hours while Early’s significantly outnumbered divisions were repulsed by Union men.

Lee later ordered reinforcements from General Anderson’s division to aid in the McLaws/Early assault. Even then, McLaws delayed the attack, and eventually when the assault commenced they too were repulsed. Lee and Early made their frustrations with McLaws clear after the battle, and McLaws would be court-martialed several months later for gross inefficiency in another campaign, although the court martial was later overturned on procedural grounds.

Late on May 6, when Lee was able to finally organize his army to attack the other Union position – under Hooker in Chancellorsville – they found only empty trenches. Hooker had escaped without the Confederates even having a chance for a final battle to crush his forces, and Sedgwick had done well enough to escape with his men. Lee’s plan for a conclusive victory had failed.

One key caveat to the argument that the South could have crushed the Union forces with a more aggressive pursuit in the closing days of the Chancellorsville campaign is that it relies entirely on the idea that Lee’s pursuit would have been successful, and beyond that, successful enough to have the desired result.

If Lee’s disappointment with Chancellorsville was that he lost so many men without destroying the Union army entirely, then surely it would have been even worse to launch a costly attack on the retreating Federal forces if he did not achieve total success in that attack. Instead of losing 20% of his men his losses would have been even more severe.

How would those men be replaced? If this theoretical greater victory was still not enough to lead to an immediate surrender, Lee would have had even greater difficulty in whatever the next major battle would have been, due to the loss of those men.

Even if he continued to inflict more casualties on the Union, barring an utter collapse, the Union would have still been able to replace men that the South simply did not have. If Lee’s aggressive plans for a follow-up attack failed, or led to a Pyrrhic victory, the war may have well been almost ended, but not in the way Lee wanted.

The failure of Lee’s aggressive pursuit is often blamed on numerous failures of his subordinates, and this assessment has a fair amount of evidence to back it up, but even better performance by generals like McLaws could not have guaranteed success.

With this important caveat in mind, the most reasonable conclusion is that Lee’s strategy was worth the risk. Lee was correct in his assessment that the North could only be defeated by a crushing victory – one that would psychologically devastate the Union and deflate their will to fight.

Ultimately a risk like Lee’s goal of an aggressive final assault at Chancellorsville would have been necessary for the South to win. Whether this one victory could have been enough by itself to convince the Union to negotiate for peace can never truly be known, but total destruction of the Army of the Potomac would have certainly increased Lee’s chances of success in his following campaign into the North.

Ultimately, Lee’s desire to entirely crush the Union army at Chancellorsville reflected an accurate assessment of the greater political factors governing the war. If successful, it had a good chance of leading directly, or indirectly after a successful follow-up campaign, to a Southern victory. Chancellorsville was truly a turning point in the war, but perhaps not in the way that many assume.

Read another story from us: A Rising Star: The Daring and Ingenious McClellan Before the Civil War

After Chancellorsville, Lee realized that he still needed a victory on Northern soil in order to convince the Northern public that the war was no longer worth fighting. He followed up his victory at Chancellorsville with a march that would end at a small Pennsylvania town named Gettysburg, where he encountered a replenished Army of the Potomac.