Like most professional armies, the Roman legions used military decorations to acknowledge superior behaviour. Though few looked like medals as we picture them today, these awards fulfilled the same function, acting as material symbols of pride and of the recognition given for great deeds. Bravery, in particular, was connected to many of these awards.

Decorations were often handed out at the end of a military campaign. The general would gather the troops for a parade and then address the assembled soldiers. Those who had done noteworthy deeds were called out and applauded by the general, who praised the heroism that had earned them the reward, as well as any previous deeds of note. The soldier was able to bask in the admiration of his peers, and given a reminder of that moment.

Hasta Pura

A blunted version of a stabbing spear no longer used by the Romans of the empire, the hasta pura dated back to the early days of Rome, when it was given to a warrior after his first battlefield conquest. Its design created a connection to tradition and a clear link to the battlefield. It was given for acts of courage, as when an ordinary soldier named Rufus Helvius saved the life of a citizen. It may also have been awarded to the principle centurion of a legion when they left their position.

Vexillum

Miniature versions of battlefield standards (vexillum) were another award that acted as a strong reminder of the battlefield, and of the fact that a soldier’s place within their unit could be as important as their individual courage.

Torcs

Though we now tend to associate them with Celtic tribesmen, torcs were popular with a wide range of people early in European history, and this extended to the Romans. Torcs were commonly used as military decorations, and Rufus Helvius received one alongside his hasta pura.

One of the advantages of a torc was that the soldier could wear it. This meant that it was more likely to be seen in public than the hasta pura or vexillum. Though the military connection was less obvious, if someone commented on the jewellery then the proud warrior would have a chance to discuss their exploits.

Torcs could have significant financial as well as symbolic value as they could be made out of precious metals. Cheaper alternatives to full-sized torcs were also used as military decorations, in the form of torc-shaped medals.

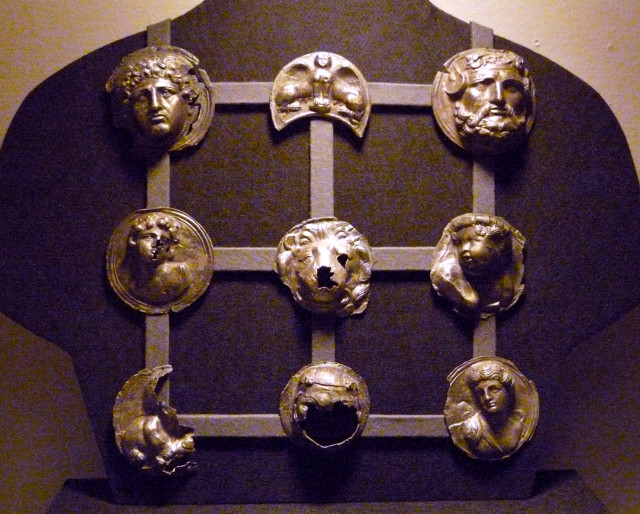

Phalerae

Similar to the torc-shaped medals were the phalerae, disc-shaped decorations that came the closest in design to modern medals. Both of these types of smaller decorations were often worn with military uniform, being attached to a harness over the armour.

Armillae

Armillae, a type of arm-band worn on the wrist, was another form of decoration that could be worn as part of a uniform. An incident in 47 BC involving an armillae highlights the inequality that sometimes existed in who received awards.

During the civil war between Caesar and other powerful Romans, an ex-slave in the cavalry was recommended for a gold armillae. General Metellus Scipio refused to grant the award because the man had been a slave. Labienus, the soldier’s immediate commander, was determined to see his deeds acknowledged and so offered to give him a reward of gold coins instead, an offer the soldier refused. Shamed into action, Metellus at last presented him with a silver armillae, an award the soldier accepted with pleasure as a proper acknowledgement of his military deeds.

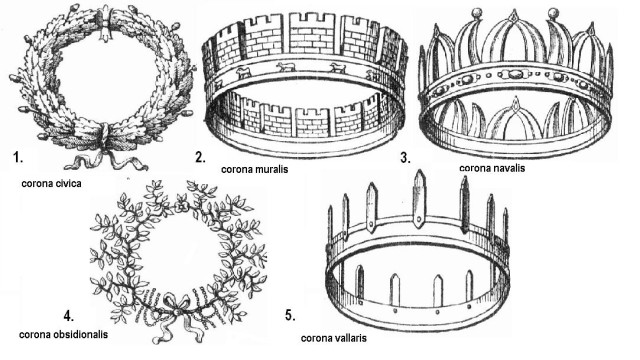

Corona Civica

Many decorations took the form of crowns. The oldest and most noteworthy of these was the corona civica, the civic crown, awarded for saving the life of a fellow citizen. For this award to take place, the citizen who had been saved had to recognise the act of bravery and make the crown himself out of oak leaves.

Corona Obsidionalis

The corona obsidionalis, or siege crown, was awarded for relieving a garrison trapped under siege. Like the corona civica, it had little intrinsic value, being made from twisted grass. But it came with the great prestige associated with a rare decoration.

Corona Muralis

Awarded to the first man over an enemy wall, the corona muralis, or mural crown, acknowledged a particularly dangerous act that required both courage and skill in combat. It was made of gold.

Corona Vallaria

Similar to the corona muralis, the corona vallaris, or rampart crown, was a gold crown awarded to the first soldier over the enemy ramparts. The existence of two specific awards for spear-heading assaults over enemy defences shows how important these actions were in the warfare of the time, and how much value the Romans placed on encouraging men in such deeds.

Civium Romanorum

Some awards were granted to entire units rather than individuals. The most important of these, and the military award that would have made the greatest difference to the recipient’s life, was the civium Romanorum.

Soldiers in auxiliary units – those made up of men who were not Roman citizens – were seldom granted individual awards. Like the ex-slave towards whom Metullus showed disdain, they were not considered worthy of the awards granted to Roman citizens. But if a unit showed particular gallantry during their time in service then they could collectively receive the most significant reward Rome could bestow – becoming Roman citizens before their discharge.

Citizenship brought many advantages for the soldiers, as they became full members of Roman society, with all the privileges that entailed. The unit would often bear the title civium Romanorum even after those soldiers had gone, as a mark of its courageous history.

Auxiliary Titles

Auxiliary units could be granted other titles in acknowledgement of deeds whose normal rewards they were not eligible to receive – titles such as armillatar or bis torquata. Over time, some accumulated whole strings of extra titles, such as the British unit Cohors I Brittonum milliaria Ulpia torquata pia fidelis civium Romanorum. Thus, the name of the unit became a form of decoration.