1. Mythical Origins

Legends tell that the Roman army began with Romulus, the mythical founder of Rome, and his bodyguard of 300 warriors called the celeres. Like much of Rome’s earliest history, it is unlikely that this is entirely true, as it was not written down until centuries later. But it shows the importance of the army in Rome, that it became part of the city’s founding legend.

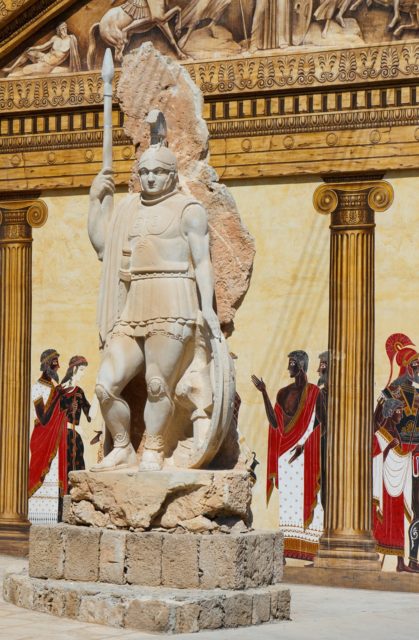

2. Stealing from the Greeks

During the early days of Rome, when it was just one small city-state in a divided Italy, much of the region was occupied by Greek settlers. Their influence spread not just through warfare and occupation but through the examples that native Italians took from them. In the case of the Romans, this included a way of fighting. They adopted the Greek strategy of fielding phalanxes of hoplites – well-armored troops carrying large round shields and spears.

Hoplites fought in close formation, their shields protecting each other, thrusting with their spears. This worked well in large battles on open ground, but for smaller raids and skirmishes older ways of fighting continued.

3. The Origin of Centuries

Centuries, the central units of the Roman army, were supposedly created by Servius Tullius, the legendary sixth king of Rome (578-534BC). Under the Servian system, a census was taken of all the men in Rome. They were divided by wealth and their military obligations based upon the equipment it was thought they could afford to provide.

Whether or not Servius actually existed, a system like this was created early in Rome’s story and endured well into recorded history.

4. Soldier Engineers

Roman soldiers were also engineers and construction workers. During the late republic and the empire, they carried axes, picks, shovels, and other equipment with them on the march. They built defensive systems wherever they camped, constructed roads connecting the empire, and labored on public works such as aqueducts.

5. So Much Marching they Wore Away Metal

The boots of Roman soldiers had metal studs on the bottom. These gave them a better grip on mud and uneven ground.

The soldiers marched so much that these studs could become entirely worn away. A group of sailors from the Italian fleet appealed to the Emperor Vespasian for money to replace studs worn away on marches between ports and Rome and were instead told that they should march barefoot.

6. They Mostly Wore Chainmail

Roman legionaries are most often depicted wearing lorica segmentata, armor made up of overlapping plates. But this was only in regular use for a couple of centuries. Most troops wore chainmail, both before, after, and in many cases during the lorica period. The Roman armor was made from iron, which rusted quickly. The mail had the advantage over the plated segmentata. It required less maintenance; as it was always in motion, it was less quick to rust.

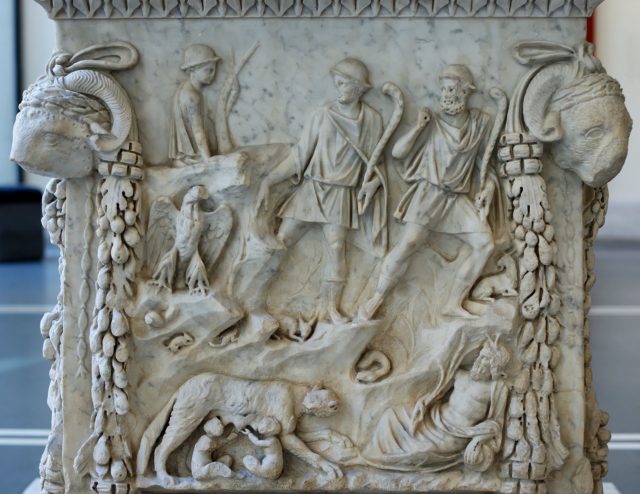

7. Not Showing Casualties

Roman art often depicted battles against barbarian enemies. To ensure that this art reinforced the might of Rome, there was a convention that enemy casualties were shown in these depictions, but not Roman casualties. Like many modern leaders, Romans liked to airbrush out the uncomfortable truth that even victorious warfare caused their people pain and loss. This can also be seen in the above image – there are dead barbarians aplenty, but no sign of Roman casualties.

8. The Army was the Government

Though the Roman Empire was headed by the emperor and the senate, the practical work of governing the empire mostly fell upon the army. Generals were also military governors of conquered regions, responsible for administering those areas. Soldiers filled the role of policemen, keeping the peace, investigating crimes, and arresting and executing criminals when necessary.

9. Many Soldiers were Cultists

Esoteric cults from the eastern end of the Mediterranean were popular among soldiers. Inscriptions from military sites show the popularity of figures such as the Hittite storm god Dolichenus and the Iranian sun god Mithras. Shrines to Mithras have been found on Hadrian’s Wall, as far from the cult’s origins as they could get within the Roman Empire. With its emphasis on strength and courage, Mithraism became particularly popular, especially among officers. Similarities to Christianity have led some to argue that this shaped or paved the way for the spread of Christianity among the imperial elite.

10. Staying Entertained

Most legionary forts had an amphitheater outside. These were used to entertain the troops through the sorts of blood sports famously on display at the arena in Rome. While provincial displays would have been far less impressive, they helped keep the troops entertained while far from home.

11. Great Care Over Health

Great care was taken to keep the legionaries healthy. At permanent forts, sewage systems and bath houses were built to maintain hygiene. Even on the march, a hospital area was often set up in the camp, with a large open space to work in.

Military doctors were held in some prestige, with many of them holding the rank of centurion. Just like knowledge of medicine, many of the doctors themselves came from Greece, and the great Greek medical writer Galen mentions a headache cure devised by the army doctor Antigonus.

12. Harsh Penalties for Sleeping on the Job

Discipline was harsh in the Roman army. A sentry caught sleeping on the job would be clubbed to death by the comrades whose lives he had put at risk, to ensure that the message was made to everyone in the unit.

The most famous way in which soldiers tried to get away with sleeping on watch was to prop up their shield and spear, using them as a support while they slept upright. How many men got away with this, how many were instead executed, and how many led their friends to disaster is not known.

13. Who Could Enlist

Only free men could enlist in the Roman army. If a slave was found to have joined, then responsibility for this crime depended on how the slave had joined up. If they had volunteered, pretending to be a free man to escape their current life, then they were punished for the fraud. If, on the other hand, they had been supplied as a substitute by another man seeking to avoid enlistment, then punishment fell on that man.