When the Roman army laid siege to a city, there were no half measures. Great effort went into preparing such an operation, the construction skills of Rome’s soldiers ensuring that the battle was half won before any combat began.

1. Logistics

Surrounding a town was a resource-heavy undertaking. Success, therefore, depended on getting materials, supplies, and manpower into place.

The attention Roman commanders paid to this can be seen in M. Fulvius’s preparations to besiege Ambracia in 189 BC. Before deciding, he checked the plausibility of this plan. Firstly, was there enough material for him to lay siege to the town, including local resources for building mounds and other siege works? Secondly, was there a river nearby to transport supplies to his army?

One example was Julian’s preparations on a grand scale when he assembled a fleet on the Euphrates for his Persian expedition (363 AD). Siege materials were packed alongside food and combat supplies. Another was when Metellus besieged the African city of Thala around 108 BC; he arranged for an entire mule train just to provide water supplies.

These logistical preparations failed during the civil war in 45 BC, when the defenders of Ursao in Spain cleared all the timber for six miles around, to discourage Caesar’s legions from laying siege to them.

2. Reconnaissance

Upon reaching the site of a siege, the next step was to reconnoitre the ground and gather intelligence. Sometimes this would have been undertaken beforehand, using reports from those who had already visited the area. A commander did not want to lay siege to a town so well defended that it could not be taken.

Part of this reconnaissance was to ascertain the enemy’s defences. Thus Flamininus at Sparta (195 BC) and M. Acilius Glabrio at Heraclea (191 BC) rode around the perimeter walls. This let the Romans see what they would be up against, to identify weak points to attack and strong points to avoid.

Understanding the terrain was also important. At Avaricum in 52 BC, Caesar examined the ground he would be working with and concluded that circumvallation – constructing a complete ring of besieging walls around the town – would be impractical. Instead, he settled on a blockade camp.

Sometimes a failure of reconnaissance and analysis stands out. When Censorinus besieged Carthage in 149 BC, he set up camp beside a stagnant lagoon. As a result, many of his troops fell sick, and he was forced to spend time and effort in moving.

3. Encampment

Following a ground inspection, the next crucial step was to construct a safe camp where the Romans would be based during the early stages of the siege. This was not unique to sieges. A Roman army on the march usually spent two to three hours at the end of each day building a defensive camp with ditches and palisades. It was particularly important during a siege when the enemy was nearby.

At Sparta in 195 BC and Jerusalem in 70 AD, the defenders launched sorties from behind their walls while the Romans were still constructing their protective camp. In this way, they hoped to catch the Romans disorganised and out in the open. Without a fortified camp to fall back to, the Romans would be vulnerable.

A painting by David Roberts (1796-1849).

The first siege encampment might be abandoned once the attack had begun and the commander gained a better understanding of the ground. Julian moved his camp after only one night during the siege of Maiozamalcha in 363 AD. Compared to building a new base every night while on a march, staying for any time in a siege camp must have seemed a restful relief to ordinary legionaries.

4. Screening

Substantial Roman siege works often included ditches, palisades, ramps, towers, and all manner of siege machines. Constructing these took time and could leave the labourers and engineers vulnerable to sorties, as in the dawn assault on ditch diggers at Erisana in 141 BC. Temporary defences were therefore needed to screen those building the siege works from attack.

One of the simplest ways of screening was to use existing terrain, as in Fulvius’s use of the River Aretho during the siege of Ambracia (189 BC). Troops could also be deployed, though this could leave the Romans thinly spread, a risk in itself. Before creating substantial siege works, legionaries often built temporary screening works.

The most dramatic of these were seen at Munda in 45 BC, where corpses from a nearby battlefield were turned into a rampart, topped with a palisade made of javelins and shields. Caesar’s famed siege works at Alesia were preceded by a range of ad hoc ditches. Screening systems were often massive construction works in their own right. At Numantia (134-133 BC) Scipio Aemilianus’s works consisted of a ditch, palisade and signalling system all around the town.

5. Demolition

One more step was often needed before full siege works could begin – demolition.

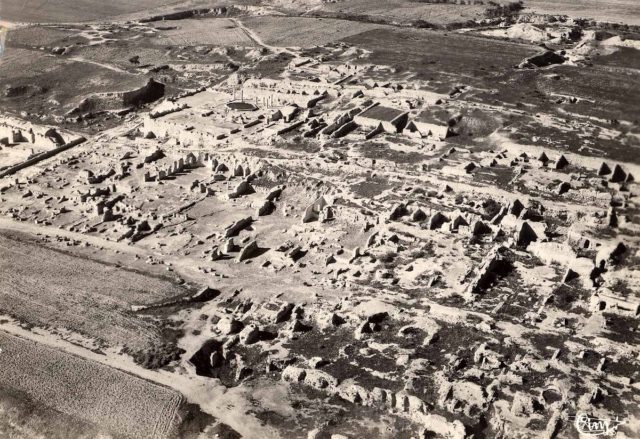

Even in ancient times, towns sprawled beyond their official boundaries. This meant that there were buildings outside the walls to which the defenders had retreated. These often had to be cleared.

The main reason for removing buildings or other features was to create open ground, both to build on and to move through. Having demolished any suburbs, the Romans could see the enemy defences and freely manoeuvre their siege machines into position.

Clearance could also supply materials with which to produce siege works. The suburbs of Jerusalem, once demolished, provided Titus with the resources he needed to build his first set of offensive earthworks.

A Roman siege consisted of far more than marching up to a town, surrounding it, and then storming the walls. Careful preparation and planning let the legions gain their famous victories.

Sources:

Gwyn Davies (2006), Roman Siege Works.

Adrian Goldsworthy (2003), The Complete Roman Army.