Given the circumstances, we know an amazing amount about the ancient Roman army. Over 1500 years after the fall of the Roman Empire fell, we know more about its military than we do for many more recent civilisations.

We know all these thanks to five kinds of sources.

Literature

Roman culture valued literature, and especially literature that told the stories of war and politics. As a result, we have a wealth of narrative information about the wars of Rome, much of it left by Romans themselves, some by their opponents. The record is not consistent throughout the empire, and we know more about periods when major historians were alive. Some saw the events they described first-hand. Polybius was at the siege of Carthage in 147-146 BC while Caesar left a full though biassed account of his Gallic Wars.

The sources have their limits. Being literature rather than history as we now know it, they seldom record technical information, and details are often vague. Polybius’s description of the finer workings of the republican legions is the exception rather than the rule. Literary conventions sometimes cloud our understanding of events, as do the biases of writers justifying the actions of their homeland or political sponsors.

For more technical information we have military manuals. Records of theoretical forms of war rather than the compromised reality works such as Frontinus’ Stratagems and Vegetius’s Concerning Military Affairs still provide a valuable insight into how men thought about war.

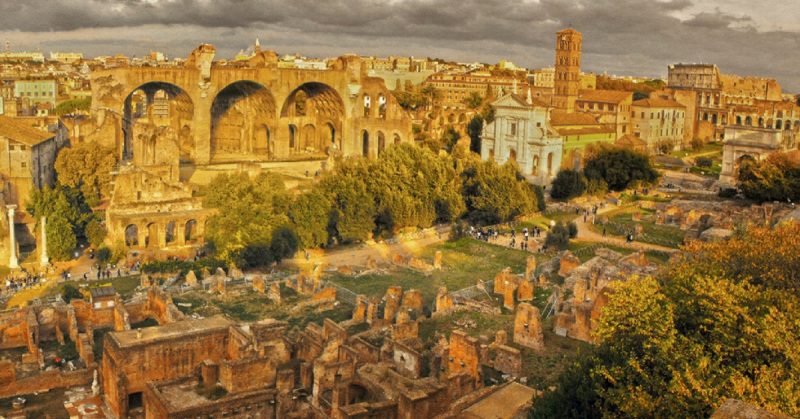

Archaeology

It is very rare for a new literary source to be discovered, lost and unexamined for centuries. Archaeological remains, on the other hand, are being found, studied and recorded in growing numbers.

Remains are most often found at places where the army was based for some time, such as forts and barracks blocks. Hadrian’s Wall has provided great insights into the life of legionaries in Roman Britain.

Rarer are finds of temporary camps such as siege lines though these have been unearthed at opposite ends of the empire, at Masada in Judea and Numantia in Spain. There show how camps were constructed and siege works conducted.

Rarest of all, and often the most fascinating, are traces of armies on campaign. The marching camps of legions were seldom recorded and leave little physical evidence, and the location of battle sites is hard to pin down. When such evidence is found, as at Maiden Castle in Britain or the exciting finds at the Teutoberg Wald in Germany, this provides valuable insights into battle’s and their aftermath.

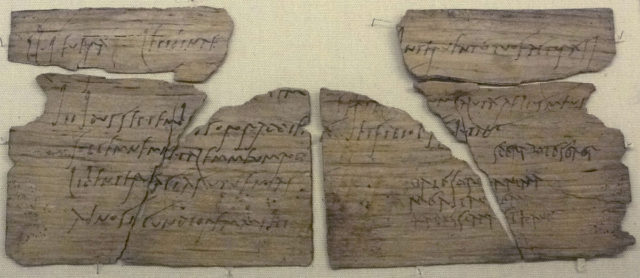

Sub-literary Sources

When we think of written evidence or records we normally think of the literary sources – the histories, chronicles and fighting manuals written by scholars and men of power. But other written evidence is sometimes found, providing a record of more mundane details and the lives of ordinary legionaries.

Literary sources have survived not in their original editions but in copies made and preserved down the centuries. Sub-literary sources, on the other hand, are the real deal, preserved by accidents of environmental conditions. For a fragile document to last two millennia takes very special circumstances, such as papyruses preserved by the dry heat of Egypt, or the wooden tablets that survived in piles of waste at the Hadrian’s Wall fort of Vindolanda.

While the literary sources provide us with the big picture, sub-literary sources provide an insight into ordinary life. Some are private correspondence while many record administrative details such as legal disputes, inventories of supplies and business dealings. They show us what the day-to-day working of the legions was like, and as more are found, so our understanding grows richer and broader.

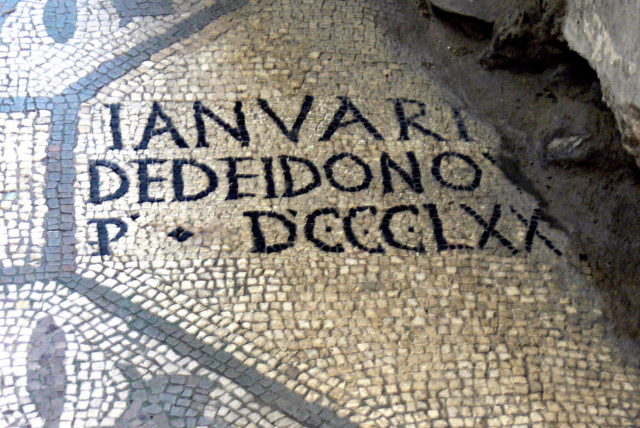

Epigraphy

The third, form of written source comes from the inscriptions carved on monuments and tombstones. Like the literary and sub-literary sources, these engravings show us the Roman army from a different angle.

The two most common sorts of inscriptions are tombstones and monuments. Small monuments were often erected to record the achievements of units, such as the completion of construction projects. Others came in the form of altars and other religious monuments.

Both tombstones and monuments, though religious in flavour, provide us with insight into far more than what the legionaries believed. The names of soldiers are recorded upon them, along with ranks, units and achievements. On an individual level, these offer a record of commanding officers. On a broader level, they show us where certain units were at certain times, and other details of army organisation. Much of what we know about the rank structure of the armies of Rome comes from these inscriptions, with their records of how men rose through the ranks.

The names of the men recorded in carvings and the gods they made offerings to can be used to draw conclusions about the ethnic makeup and geographical origin of specific units and the army as a whole. These conclusions are always a little speculative, but give an idea of the diverse nature of the legions.

Art

One of the reasons why Europeans have remained so fascinated by their Roman past is the magnificent remains the Romans built across the continent and beyond. Their artistic endeavours, and in, particular their carvings, have stood the test of time, allowing us to learn more about the appearance and actions of the legions.

While archaeological remains provide the most detailed and reliable insights into legionary equipment, carvings show us details usually lost to archaeology. Cloth and leather quickly rot away, but stone imitations can last for millennia. Tombstones again play a part, as does public art and architecture.

The most impressive record of the Roman army is Trajan’s Column, built in Rome to celebrate the Emperor Trajan’s victory of 106 AD over the Dacians. While it shows an idealised army, it shows a great deal of details and information on auxiliary troops and different forms of uniform, as well as events in the Dacian campaign. The Tropaeum Traiani at Adamklissi, now in Romania, shows the same campaign more realistic point of view and demonstrate the legionnaire’s equipment and everyday duties.

Source:

Adrian Goldsworthy (2003), The Complete Roman Army.