Tactically, the purpose of a siege is almost always the same – to take control of a strongly defended position. The reasons for launching one are far more varied. The ancient world’s masters of siege craft, the Romans, laid siege for a wide range of strategic goals.

Capturing Key Settlements

Sieges of towns often took place because of the strategic importance of those settlements. They could be key ports, capitals of enemy nations, or be in some other way vital to the society, economy, and politics of a region.

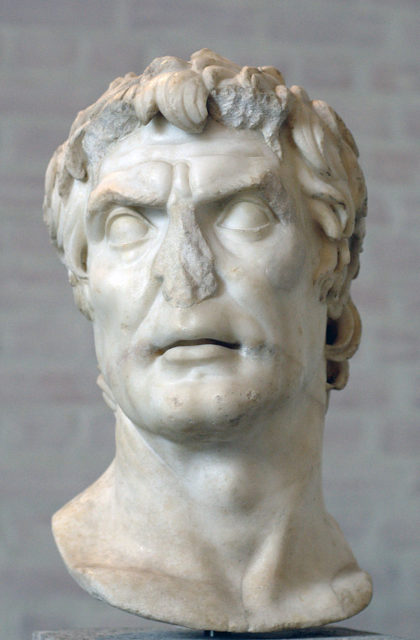

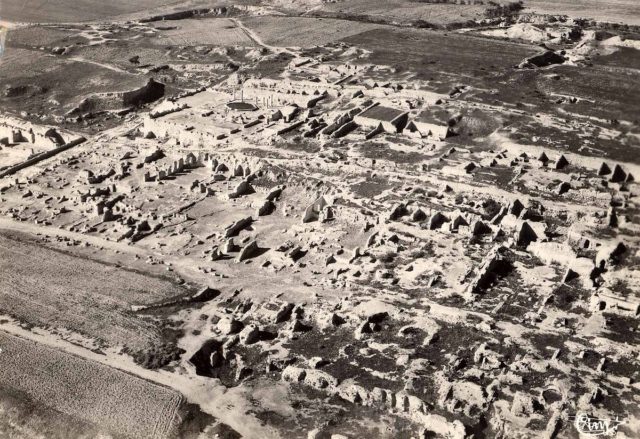

No siege better demonstrates this than the long Siege of Carthage undertaken by Scipio in 149-146 BC. Carthage was Rome’s greatest opponent in the Mediterranean. That sea provided the primary means of trade, transport, and communications. Any political or commercial empire would be held together by it.

As Carthage recovered from previous setbacks, it was once again becoming the greatest port in the Mediterranean. A capital from which merchants and colonists would venture out – all over a world the Romans wanted to dominate. So the Romans set out to destroy the economically and politically vital Carthaginian capital. Years of effort, piles of gold, impressive feats of engineering, and the strict discipline of Scipio all went into a siege that eventually ruined Rome’s greatest rival.

Destroying the Enemy’s Capacity to Wage War

Some sieges were not so much about the fortified place itself. They were more about preventing an enemy from making war. By whittling away troops and supplies, cutting them off from joining the enemy, or forcing armies to surrender, the Romans could prevent their enemies campaigning against them.

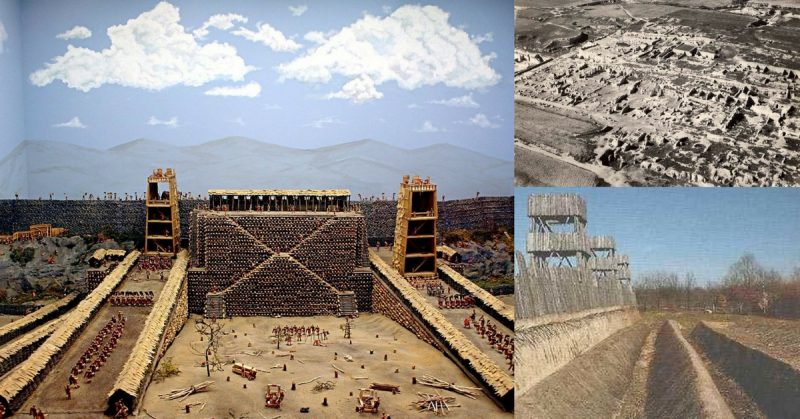

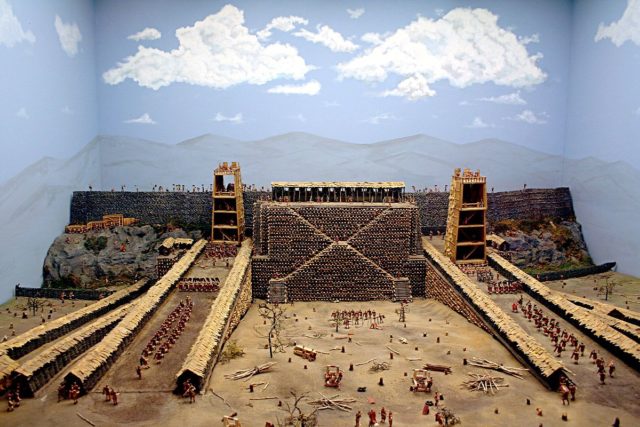

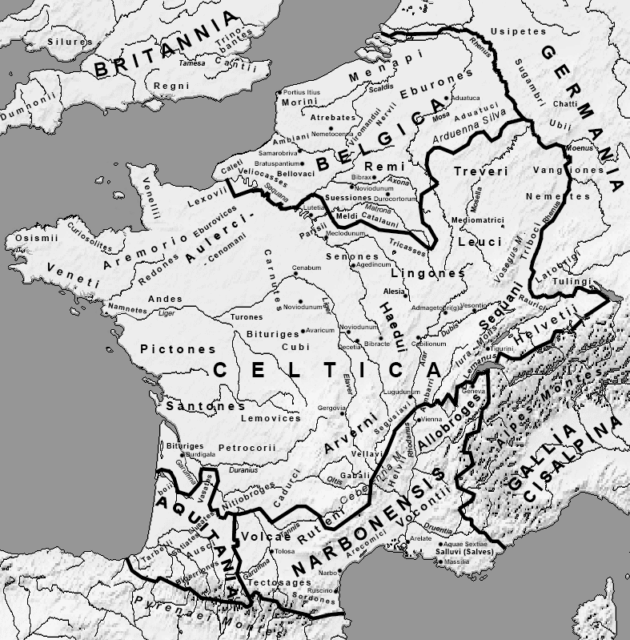

An example of this can be seen in one of the most famous sieges in Roman history, Caesar’s siege of Alesia (52 BC). The Gallic chief Vercingetorix gathered the main part of his army at a hill fort on a plateau, protected by rivers and steep slopes. Caesar had his men construct an elaborate ring of siege works around the site, including both inward and outward facing walls, ditches, and traps.

The Gauls inside the fort were unable to attack the Romans. Once a relief force was defeated, Vercingetorix was forced to surrender and the Gauls’ capacity to fight was all but destroyed.

Breaking up Concentrations of Troops

One part of destroying an enemy’s capacity for war was breaking up concentrations of troops. By driving a force out of a fortified position, the Romans could prevent it from safely staying together. Men, unprotected by walls, were more likely to defect. Without a stable base of operations, it was harder for new forces to find and join an existing army.

This can be seen in the siege of Mount Medullus (26 BC) and the siege of Uxellodunum (50-51 BC). The latter followed Vercingetorix’s defeat at Alesia. Uxellodunum had become the remaining center of Gallic resistance under the leaders Drappes and Lucterius. Caesar’s siege, which used tunnels and siege ramps, broke the final concentration of Gallic troops, preventing discontents from rallying against him.

Breaking Enemy Morale

Some sieges were about making a point. One of these was the siege of Avaricum (52 BC), part of Caesar’s Gallic campaign.

As he progressed through Gaul, Caesar had his troops raid the towns they passed. Like pillaging throughout history, this achieved two things. Firstly, it provided supplies for his army. Secondly, it struck fear into the opposing population. By showing that resistance meant suffering, Caesar hoped to shake the morale of his enemies.

Avaricum was the most symbolically important example of this. A prosperous town that played a vital role in the regional economy, it resisted when Caesar and his men arrived. It was not militarily significant – Vercingetorix tried to persuade the inhabitants to leave rather than hold it. Caesar laid siege to the town and let his troops run riot after it fell, making a point to the rest of Gaul – resistance to Rome could be deadly for all involved.

Protecting Lines of Supply

One of the towns attacked by Caesar and his troops on the way to Avaricum was Vellaunodonum. Like the other settlements attacked in this way – places such as Cenabum and Noviodunum – Vellaunodonum provided an opportunity to gather supplies and to put the fear of Rome into the Gauls. But there was also an element of necessity to this siege.

As Caesar recorded in his account of the Gallic Wars, the Senones town of Vellaunodonum was a potential threat to the Roman supply lines. It could not be left unconquered as he advanced. So he surrounded the town, forcing its inhabitants to surrender after just three days. With his lines of communication and supply secured, Caesar moved on.

Drawing out the Enemy

Sieges could be useful in drawing out enemy troops and forcing an opponent to fight. A force suffering from an extended siege might charge forth to destruction when it had previously remained safely behind its walls. Other troops in the surrounding region might march forth to try to relieve the siege, exposing themselves to attack by the Roman army.

This was a tactic that Caesar used several times during the civil war, including at Thapsus (46 BC), Ategua (45 BC), and Dyrrachium (48 BC).

It was also used successfully by Sulla in his defeat of the Marians in 82 BC. On this occasion, it was the siege of Praeneste by Sulla’s lieutenant Ofella that made the difference. Ofella’s aim was not to take the town by force, so he built his siege lines far back from the walls. As the inhabitants were slowly starved, several relief forces were sent by other Marians in the area. These were defeated by Sulla’s field army, allowing him to destroy his opponents without the bloody cost of assaulting fortifications.