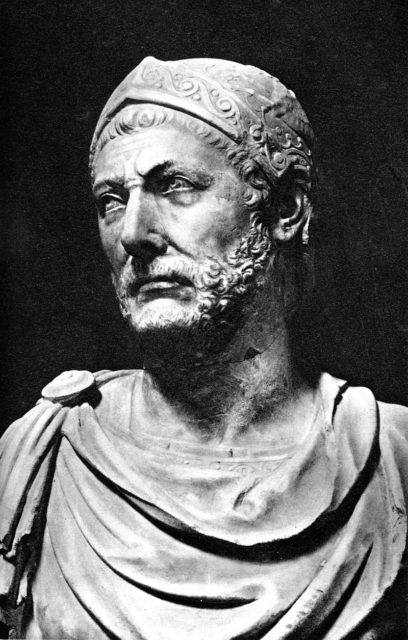

The Carthaginian General Hannibal was the greatest opponent Rome faced. He repeatedly defeated the Romans in battle, most famously at Cannae in 216 BC. For 15 years, his armies marched up and down Italy, dominating the Roman heartland.

In the end, the Romans won. How did they defeat such a formidable opponent?

Etruscan Loyalty

After proving his power against the Romans, Hannibal tried to persuade the Etruscans to defect to his cause. Another Italian people, the Etruscans had been the dominant power in the region before the rise of Rome and were among the first to be conquered by the legions. There was every reason to believe they might want to throw off Roman shackles.

The Etruscans did not defect. Whether from fear, loyalty, habit or seeing the benefits of working for Rome, they stuck with their masters.

War of Attrition

It took several devastating defeats for the Romans to accept they could not beat Hannibal in a pitched battle. Once they acknowledged that fact, they found another way to wage war. They settled in for a grueling war of attrition.

Siege warfare, a Roman specialty throughout their history, came into play. Hannibal could not protect all the rebel cities that had joined him. One by one, these were retaken by the Romans as they clawed back control of the peninsula one settlement at a time.

Fighting Spirit

The Romans had tremendous fighting spirit. Such was their formidable sense of self-worth they were unwilling to admit defeat. They were the descendants of Romulus and Remus, the founders of Rome, the best of the best.

Mere battlefield defeat and a decade of enemy troops on their land would not persuade them otherwise. Against all the evidence, the Romans believed they were the best. It was a belief that made itself come true.

Massive Manpower

Flinging massed legions against Hannibal had not solved Roman problems at Cannae or the battles which preceded it. Manpower was necessary. It allowed the Romans to fight a long campaign featuring numerous sieges. One of their most critical responses to Hannibal was to recruit more men.

Year after year, more legions were trained and put into the field. The army sent to Cannae consisted of eight legions and was considered a massive force.

By 212 BC, Rome had over three times that number; 25 legions.

Withdrawing Behind the Walls

One of the most significant moments in the war came when Hannibal reached the gates of Rome itself.

With both pride and military power on the line, he must have felt there was a good chance of open battle. If the Romans could be persuaded to come forth from their City, then he could defeat them and seize the capital.

However, the Roman forces held back. Whether motivated by fear or strategy, they overcame their pride, bolted the gates, and refused to give battle. Hannibal’s forces were impressive, but not strong enough to take the capital of an empire by force. He backed off and the symbolically, economically, and administratively vital city held. The war continued.

The Defeat of Hasdrubal

The turning point in the war came in 207 BC.

Hasdrubal Barca, Hannibal’s brother, arrived in Italy with reinforcements. Before he could join Hannibal, Hasdrubal was intercepted by a well-prepared Roman army at Metaurus. The Carthaginians were soundly defeated, and Hasdrubal was killed.

Hannibal learned of his brother’s arrival in Italy when Hasdrubal’s severed head was flung into his camp.

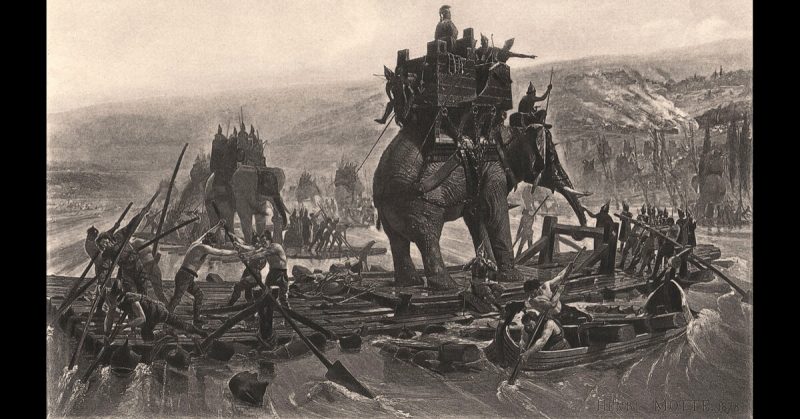

Control of the Sea

Generations before, when Rome and Carthage first went to war, Carthage had been the greatest naval power in the Mediterranean. Those days were at an end.

Although the Carthaginians were among the finest sailors in the world, the Romans had a larger fleet. They had invested in ship building, copying Carthaginian designs to build ships that were as powerful if not more so than those of their opponents.

Once battle commenced, the Romans had the advantage of better fighting men drawn from the legions. Ancient sea battles were mostly fought using boarding actions, which worked in the Romans’ favor.

Through its large navy, brutal sailors, and control of coastal cities, Rome dominated at sea. It made getting fresh troops and supplies to Hannibal difficult, dangerous, and time-consuming.

Colonies

Roman colonies were strategically important in the war, in Italy and beyond. They provided bases in which the Romans could hold out against the Carthaginians. Attacks could then be launched from behind enemy lines, making Carthaginian holdings insecure. Settlements along the coasts of Italy, Gaul, and Spain gave them the ports they needed to supply and shelter their fleets.

Successes in the war had become self-sustaining; previous conquests were fuelling the Roman military machine.

Scipio

In 210 BC, the Roman Senate gave command of the war to Publius Cornelius Scipio. At 27 years old, he was the youngest Roman ever to be given such a responsible position. His appointment proved as wise as it was unprecedented.

Smart, charismatic, and with boundless energy, Scipio showed the strength of spirit that marked Roman resistance to Hannibal. A survivor of the disaster at Cannae, like any good Roman, he saw shame not in defeat but in giving up.

Scipio took a leading role in the aftermath, taking an army to Spain, where both Carthage and Rome had planted colonies. There he conquered the city of New Carthage, providing himself with a base, and drove the Carthaginians from the region.

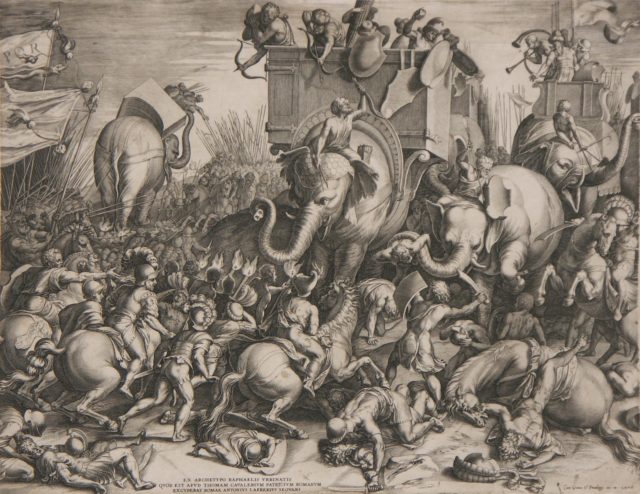

After Spain, Scipio led his armies to Africa. There he oversaw the final defeat of Hannibal at the Battle of Zama in 202 BC. On his return to Rome, he celebrated a spectacular triumph and took on the name Scipio Africanus in memory of his achievements.

Hannibal had been beaten, and Rome returned to dominate the Mediterranean world.

Sources:

Adrian Goldsworthy (2003), The Complete Roman Army.

Adrian Goldsworthy (2003), In the Name of Rome: The Men Who Won the Roman Empire.

General Sir John Hackett, ed. (1989), Warfare in the Ancient World.