In the 8th century, a fractured collection of European kingdoms came under increasing pressure from the powerful united Caliphates of the rapidly developing Islamic world. On the whole, the defense of Western Europe was held by three geographic points.

In the west, Spain was a massive battleground where the tide ebbed and flowed around the Pyrenees between Modern France and Spain. In the east, Constantinople and the Byzantine empire faced some of the most concerted attacks. The other main location was Italy.

In the 8th century, the Ummayid Caliphate was dealt a decisive blow at the battle of Toulouse and Tours, checking their advance into France. Also in the 8th century came the massive siege of Constantinople. The Ummayid failure there cost them thousands of lives.

Raids on Sicily in the 8th century were relatively light, keeping Sicily and Italy relatively safe. Eventually, however, some rebellion within the Byzantine navy in Sicily left sea routes open to an invasion. The Saracens lanched raiding parties, and while they failed to take Syracuse, they were able to secure a handful of other fortresses and gained a foothold on Sicily. The conquest of Sicily was grueling. The invaders faced entrenched mountain fortresses such as Enna in central Sicily and sea-supplied legendary cities like Syracuse and Messina.

Eventually, the Saracens secured Messina, on the northeast corner of the island closest to the toe of Italy. Through their Sicilian conquests, the new rulers of Sicily heard about the amazing plunder that could be found in the ancient and religious city of Rome.

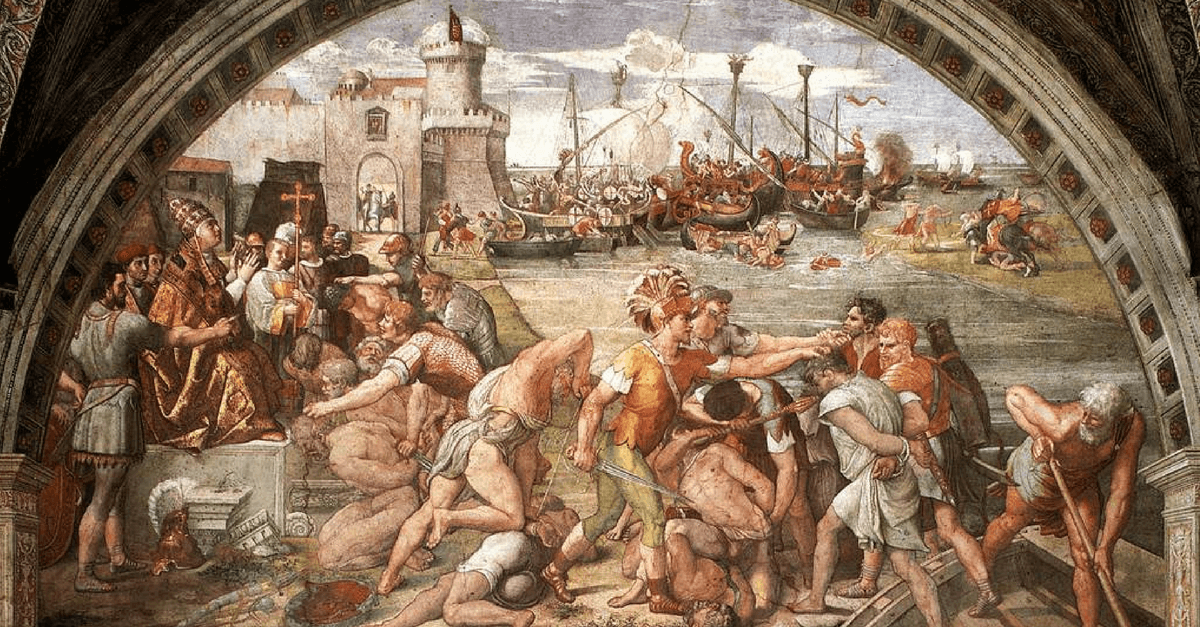

Raids progressed to the point where the Saracens were able to get a small foothold in Italy at the city of Miseno on the Bay of Naples in 845. From here a sizable group sailed up to the port city of Ostia, the historical port city of Rome. The small garrison of the undefended Ostia was slaughtered. The Saracens sailed and largely marched up the roads along the Tiber to Rome.

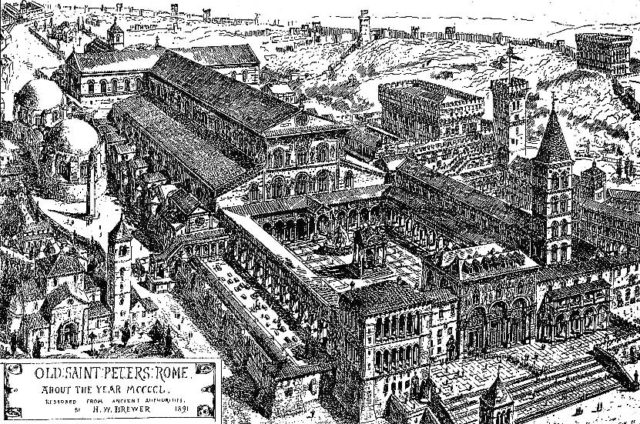

From their time in Sicily and Italy, the invading army not only targeted Rome for the known wealth, but they seem to have known exactly which locations to target. They went straight for the Basilica of St. Paul outside the Walls and the Old St. Peter’s Basilica, also outside the walls.

Some of the Papal guard attempted to stop the plunder but were hopelessly outnumbered. Few who were outside the walls survived. The walls in question were the Aurelian walls of Rome. These were walls built way back during the height and beginning of the decline of the Roman Empire. In the 3rd century, Rome itself still held a great deal of power despite rebellions and barbarian incursions. The uncertainty of the Romans led to the construction of the Aurelian Walls.

These walls were further reinforced during the increasingly turbulent times at the end of Rome in the West. By the time the Saracens arrived in 846, the walls were about 600 years old but full of tunnels and clever fortifications that allowed the small Roman garrison to fend off some scattered attacks. No literary evidence exists for a concerted Saracens attack on the walls, but more than likely they probed here and there to see about finding an easy way to take a gate or undefended section.

The raiders continued to plunder the wealth of buildings and loot outside the walls, likely exchanging missile fire with the defenders on the walls. The Saracens didn’t fear a counterattack from the defenders, likely meaning that they had a significantly larger force. The elation of more loot than they could carry didn’t last long for the Saracens as an army headed by Lombards plunged south from Spoleto. The large and well-equipped army pinned the raiders against the walls.

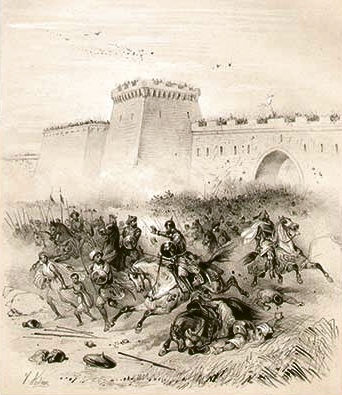

The Saracens were loaded with booty and couldn’t respond to the attack. They were soon scattered. One group attempted to head down to their ships at Ostia and another group tried to make it down to Miseno on foot. The Lombards pursued those heading to Ostia and many of the Saracens were still able to get back to their ships. A quick storm kicked up and shipwrecked most of the Saracen ships where the Lombards were able to recover most of Rome’s stolen goods.

Near Miseno, a more significant group of raiders got close to Naples before the Lombards could catch up. Here a more traditional battle seems to have been fought, perhaps with reinforcements from Miseno joining the fray. The battle seems to have been very closely contested and was only won by the defenders when a group of men came out to fight from Naples to finally turn the tide.

The close call at Rome prompted extensive works on more fortifications at Rome. The area most heavily raided was enclosed in walls and other areas were fortified. Ostia was also much better defended and manned. In another raid a few years later, the Christians would win decisively at Ostia, not letting the Saracens penetrate towards Rome this time. Had the raid on Rome been more successful, perhaps Italy would have been pursued further by the more prepared Caliphates. Thanks to the still present Aurelian Walls, Italy remained secure.