Rome after Caesar’s death was a place of great uncertainty. Caesar had a long road to secure power and had finally secured it, and seemed to be doing great work for Rome, though as a tyrant, before his assassination.

If those behind the assassination thought they would be applauded they were sorely mistaken as the two people with the most support after Caesar’s death were his second in command, Marc Antony, and his posthumously adopted son (formerly his grand-nephew), Augustus.

True to the style of Roman “politics” at the time, the two men formed their own armies and fought for control, but this time a temporary peace was brokered in order to combat the rebel factions of Caesar’s killers.

This alliance was known as the second Triumvirate, as Caesar, Pompey and Crassus formed the first and Octavian and Antony were joined by Marcus Lepidus for the second. Much more official than the first, the second triumvirate was given near absolute power almost essentially replacing the Republic with an Oligarchy.

The members would divide Roman territory among them and rule each as equals. As Antony held the most powerful position at the time he elected to rule the Roman East. The East had far more people to serve in armies, it was extremely wealthy and had an abundance of food thanks to the fertile Nile.

Octavian choosing second, took the Roman northwest, which was far less developed in many areas and much poorer, but contained Italy and Rome itself. Lepidus was relegated to the decently wealthy and self-sustaining region of Africa and largely forgotten about.

Antony was beyond happy ruling from Egypt and began his romantic involvement with the powerful Cleopatra. He was a skilled general and natural leader and was confident in his ability to defeat Octavian if need be, and tensions between the two began to rise again.

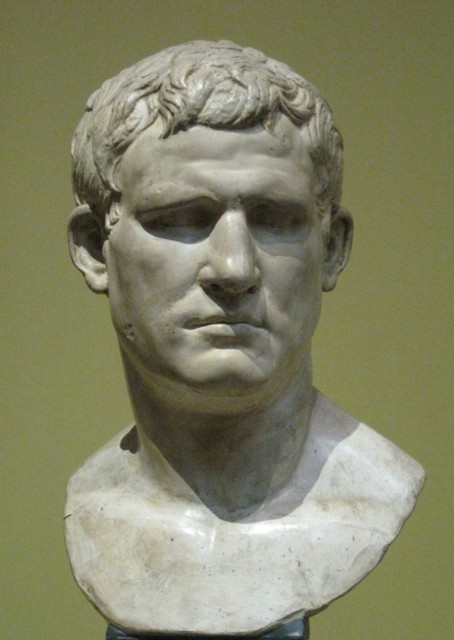

Octavian was a remarkably intelligent man, learning from the past civil wars and became a master of political and grand strategy. He also was well aware of his flaws, he was small and often sick, and had little talent in command. Octavian had great talent in being able to put the absolute best person for the job in every position he needed.

The best example was his use of his childhood friend Agrippa as his chief commander and military advisor. Agrippa was an outstanding tactician and had no problem leading from the front. As skillful as he was, Agrippa had no problems winning a great victory and stepping back to allow the credit to go to Octavian. Agrippa seems to have simply had no desire for more power than he had.

As tensions rose between Antony and Octavian, it seemed that Antony was ready to either make a move to attack Octavian or perhaps succeed his eastern holdings and form a new kingdom with Alexandria as his capital. Octavian used propaganda against Antony saying he was a slave to Cleopatra and had adopted Egyptian customs and betrayed the Roman people. War soon became inevitable, and Antony moved a large army and navy to western Greece, very close to the border of Octavian’s territory.

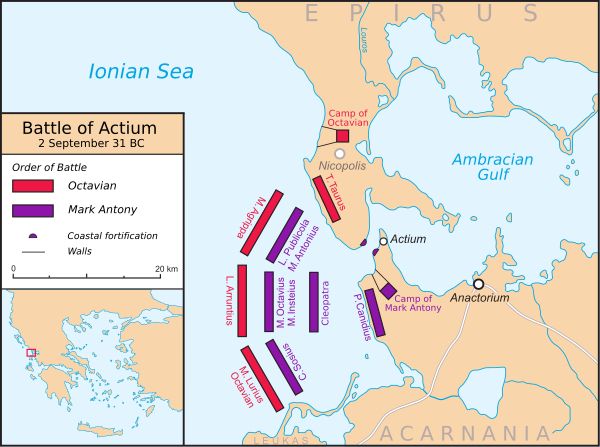

Antony had fortified many of the towns of western Greece and placed his forces in a small gulf just north of the gulf of Corinth. This was a defensive, but smart strategy. Antony knew that Octavian would have to sail from Italy to reach him and hoped to ambush the vulnerable transport ships.

Agrippa sensed this trap and rather than fall into it, Agrippa took a sizeable naval force around southwestern Greece, past the fortified towns and took the city of Methone. From here he began raiding other areas and forced Antony to respond for fear of losing his supply lines. Agrippa’s distraction worked perfectly and allowed Octavian to safely land his forces in northern Greece Antony had a heavily fortified position on the southern coast of the gulf while Octavian set up on the northern coast.

Antony did not want to leave his fortified position nor did Octavian want to attack it. Agrippa took advantage of this stalemate by raiding along the coast. Agrippa’s raids were wildly successful, so much so that he succeeded in taking several of the fortified towns and almost completely crippled Antony’s supply lines. The morale of Octavian’s forces grew with news of each small victory while Antony’s forces faced hunger and sickness.

From the evidence, it seems that Antony planned to break out of the gulf and save as much of his force as possible, knowing that he was now in an impossible position. His men pleaded with him to fight a land battle, as that was their, and his area of expertise, but many said that Cleopatra influenced him into a naval engagement.

On September 2nd 31 BCE, Antony sent his ships to the mouth of the Gulf, forming a single line with three equal sections, though all of Cleopatra’s ships were huddled in the rear. Antony had as many as 230 ships compared to Octavian’s force of up to 350 ships. The two forces were vastly different, however, as Antony’s ships were mostly massive Octaries, massive ships with eight banks of oars, compared to the standard ship of the day, the Trireme. Antony and his admirals even had Deceres with ten banks. These ships were essentially floating castles with wooden towers and artillery.

Octavian had much smaller ships, mostly two to six banks of oars, though a lot more total. His plan was to let Antony push past his ships and collapse on them as they maneuvered around. Thankfully Agrippa advised against this strategy and elected to form a blockade at the mouth of the gulf to force Antony to attack.

Had Octavian’s plan been followed it may have worked perfectly for Antony who seemed ready to simply flee for Egypt. Given the chance, many warships left their sails on shore before a battle for greater mobility under oar power, but many of Antony’s ships carried their unused sails on board. Antony waited in the mouth hoping to entice Octavian’s force into a bottlenecking attack, but Agrippa gave strict orders to wait, knowing that Antony was desperate and would ultimately have to attack.

As Antony powered forward, ships met all along the lines in small groups while Cleopatra’s force stood in reserve. Antony’s largest ships were surrounded and boarded by groups of three or four others in what looked like multiple assaults on wooden fortresses. Many ships had powerful Ballista that could direct fire to the deck or at the rowers. Though Octavian’s men seemed to have the advantage, taking each ship was a monumental challenge and the battle lasted for hours.

Eventually, a gap opened right in the center of the lines and without hesitation, Cleopatra’s ships hoisted their sails and sailed straight through and to Egypt. Antony, seeing this, got himself to a smaller and faster ship and left the battle as well through the same gap. Had Cleopatra’s forces wheeled around and attacked the flanks of Octavian’s forces the battle would have at least been much more closely contest, but after they fled the rest of Antony’s abandoned fleet fell apart. The struggle was still immense with some large ships holding out for several more hours, but the battle was won.

Antony may have thought that he could gather more forces but after the battle of Actium he had a terrible reputation, no navy and almost no hope of raising another army. Rather than surrender and accept defeat, Antony and Cleopatra committed suicide about a year later.

Octavian had defeated his last major rival, with Lepidus being a minor player by this point. The battle was won decisively by Agrippa from the decision to bypass the fortified towns and raid southern Greece to the successful raids during the stalemates and finally through asserting the best plan for battle and executing it to perfection.

Again, Agrippa was more than willing to stand aside and officially Actium became the glorious victory of Octavian as he began consolidating the powers of various offices.

Learning from his predecessors, Octavian did not claim to be dictator or Emperor, but instead took the title of “First Citizen” and duped the Roman people into willing accepting an empire that would last centuries

By William McLaughlin for War History Online