The Carthaginians made many mistakes during their ill-fated Punic Wars with Rome. In the first two, they fought wars of attrition against the most stubborn populace in the Mediterranean. After losing navy after navy in the first war, the Roman elite paid for a new fleet from their own pockets, a fleet that would go on to win the war.

After Cannae in 216 BCE, a brutal defeat capping a string of disastrous years for Rome, the Romans applauded the returning defeated general, thanking him for not losing faith in the Republic. Then they got to work grinding down Hannibal’s position.

Less than ten years after Cannae, many of Hannibal’s gains in Italy had been retaken. The traitorous great cities of Syracuse and Capua, both rivals of Rome in their own right, were taken bay force. Hannibal still had a sizeable army, however, and by early 207 BCE, his brother Hasdrubal had crossed the Alps with a large reinforcing army. Hannibal had been kept in check in southern Italy for years, but had some successes with his moderately sized, but veteran army. Just a year prior, 208, he had ambushed and killed both Roman consuls in one raid.

Though Rome had been having sustained success the idea of another army under a Barca invading Italy was terrifying. Even more frightening was the idea of Hannibal and his brother Hasdrubal linking their armies. Such a force would be as large as 60-80,000 men, as many as the Romans ever had in a single army before. With such a force, Hannibal would have the option of steamrolling through smaller cities, intimidate other towns into forming alliances against Rome, and he could divide and conquer with his skilled and loyal brother able to command detachments.

It was even feasible that the united force could besiege Rome itself. The deterrent previously had been that Hannibal’s force would be left defenseless to being surrounded as well by relief forces With such a large army, Hasdrubal could command the siege while Hannibal dispatched incoming relief armies as they arrived. Stopping this unification of the armies was the highest priority for Rome.

Luckily for the Romans, their furious recruitment through the years gave them more than enough forces to defend Italy. There were two possible paths that Hasdrubal could take to meet up with Hannibal in Southern Italy; he could cross south through the Apennine Mountains and pass by Rome, or go south-east along the coastal route.

Considering the defenses around Rome, the difficulty of crossing yet another mountain range in addition to the Alps, and the fact that Hannibal had lost an eye to disease while going through a swamp on the Apennine route, Hasdrubal decided on the coastal route. Nevertheless, the Romans had to have full armies defending both routes, just in case, and another full army keeping Hannibal occupied.

The Roman strategy for Hannibal was rather genius, they engaged Hannibal’s army in multiple small battles and skirmishes. They absorbed multiple small losses to keep Hannibal in a constant state of recovering his army from the latest engagement. By doing this and keeping forces always near, Hannibal had no chance to head north to meet his brother.

Hasdrubal had sent a message to Hannibal with swift Numidian riders indicating his march along the coast. This message was intercepted by the Roman consul Gaius Claudius Nero, tasked with shadowing Hannibal in the South. Knowing that the division of the Roman armies meant that they may be left under-strength to handle Hasdrubal’s forces, Nero devised a plan to get aid to his fellow consul, Marcus Livius.

Nero took a core of his best troops, about 7,000 in total and secretly slipped away from Hannibal, giving his remaining army instructions to be extra cautious and not reveal the loss of so many men, lest Hannibal realize this and attack the depleted shadowing army.

Nero raced with incredible speed to Livius’ position. Hasdrubal had already met Livius’ army, and was willing to engage, but Livius stalled for time, slowly retreating southward. Nero’s 7,000 men marched hard, but the journey was made easier as it was through friendly territory. Italians along the route knew the importance of the battle and marching soldiers were given fresh food and places to rest and ox carts provided to place the truly worn out men to recoup and march again.

Nero hoped to bait Hasdrubal into fighting what looked like one medium-strength consular army, and so had his 7,000 men arrive in the dead of night and share the tents already in place. Though Hasdrubal’s camp was less than a half mile away he had no idea of the vastly increased size. It was only through pre-battle scouting that Hasdrubal was given word that trumpet calls had sounded two times, signaling the presence of two consuls. Fearing a vastly larger army, Hasdrubal retreated along the Metaurus River, though closely pursued by the two consuls.

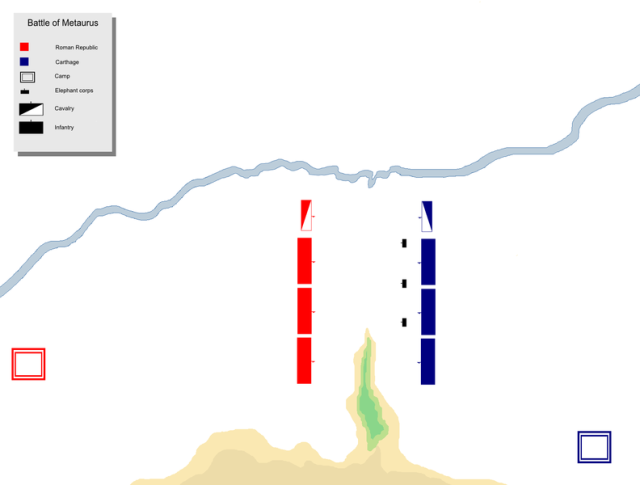

Hasdrubal was unable to find a crossing, becoming dismayed as the river only became wider and deeper the more his scouts looked. Finally accepting that he must fight Hasdrubal devised a cunning strategy. Using the river to anchor his right flank, Hasdrubal found a rocky hill to protect his left, stationing his least reliable Celtic warriors there.

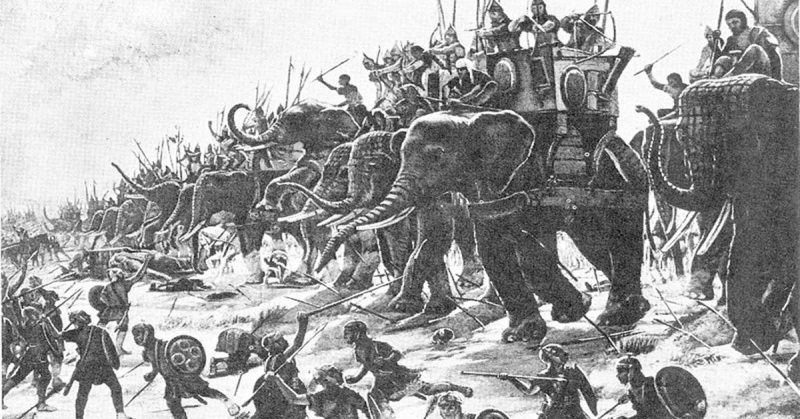

Hasdrubal likely had anywhere from 25-35,000 men, some veterans from Spain, several elephants and the above-mentioned freshly recruited Celts. Hannibal had had success using his veterans to put perfect pressure on the Romans and Hasdrubal planned to use the same tactics.

Hasdrubal’s plan was to push through the Roman’s left with the combined force of his elephants and elite troops while keeping his Celts out of the fight defending the high ground. The Romans were a mix of fresh but trained recruits and those who had experience fighting against Hannibal. Many of the officers and commanders had experienced battle at least in some form over the years.

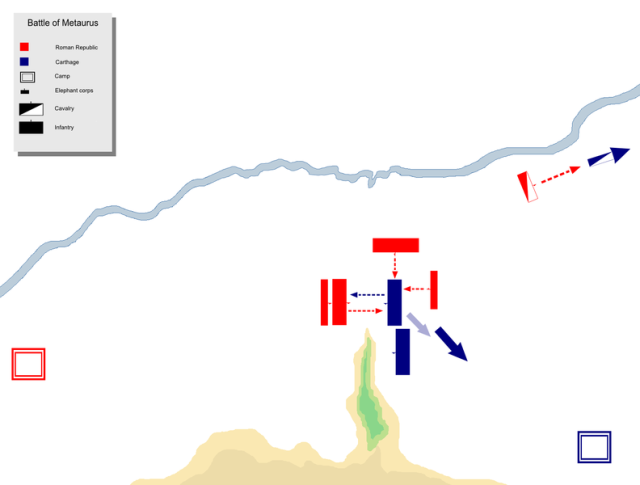

When battle broke, the Romans, in their standard formation, found their left hard pressed. Nero, for all his work intercepting the message and force marching, found himself on the rather boring right flank. Seeing that relatively few Celts could easily defeat or at least greatly stall his forces in an uphill attack, he devised a new plan.

Taking some men from his rear lines, so as not to give his plan away to the Celts as much, Nero led them on a wide march behind the rest of the Roman army’s lines. By the time he reached the Roman left Hasdrubal’s plan had almost been successful.

The elephants had mostly pushed through, causing massive devastation in the Roman lines. some elephants were turned back on the Carthaginian troops in an unstoppable rage and it is here we get one of the very few examples of riders hammering a stake into the base of the skull to kill the rampaging elephant, possibly even a tactic invented by Hasdrubal.

The elite troops, mostly Iberians, threatened to collapse the whole Roman left, they were already working well around the flanks. Nero’s forces arrived in time to counter-flank, crushing the Iberians and killing any elephants still left in the fight. Once the Carthaginian flanking attempted was crushed the Roman left pushed through and did what Hasdrubal couldn’t, routing the opposite flank.

The key discussion on the differences in the battle descriptions comes from rather unclear sources. Polybius states first that Hasdrubal stationed his ten elephants along the length of his lines, but then only references them again when mentioning the Roman left. Nero’s flanking movement attack according to Polybius was directed right “where the Elephants were”. So it would seem that Hasdrubal did put at least the majority of his elephants on his right, or at least quickly directed them to attack there, as Livy indicates.

Also, Polybius does say that the fighting was even until Nero’s flanking attack. With Hasdrubal specifically anchoring his flank with the Metaurus, it is hard to see how Nero worked through what must have been a small or even nonexistent gap to flank, leading one to believe that Hasdrubal’s strong push must have had some success against the Romans to even give Nero’s force an opportunity to flank.

The cavalry for both sides seems to have been focused near the river, and the Romans superior cavalry could explain how a gap large enough for Nero’s flank was created. Unfortunately, the cavalry’s role in the battle is not well discussed by Polybius or Livy.

Hasdrubal’s army fell around him. He had come up with a solid tactical plan with his smaller army, but the Romans had too much experience fighting Hannibal to let their larger army be defeated. Hasdrubal, thinking his army lost, and also supposing that Hannibal might be lost, considering Nero was able to come north to confront him, charged into the Roman lines to his death.

Polybius and Livy our main sources, commend Hasdrubal as a fine example of a great general, forming a solid plan and fighting bravely to his death when all was lost.

After the victory, Nero made another hasty march back to his former army, with Hannibal none the wiser until a Roman scout threw Hasdrubal’s severed head over the camp walls. Hannibal knew then that Carthage had no real hope of winning this war.

The Romans were beyond relieved, they not only prevented a junction of two large armies in Italy, but they had destroyed Hasdrubal’s army and killed the commander, Hannibal’s own brother. It would take several more years of fighting, the impressive victories of Scipio had to accumulate enough to bring Hannibal back to Africa to fight the decisive battle of Zama. Only after Scipio had beaten Carthage’s greatest general did they completely surrender.

By William McLaughlin for War History Online