The end of summer in the 16th century for Hungary was marked by one of the bloodiest sieges of their history. The Habsburg Monarchy suffered a heavy defeat at the hands of the Ottomans. The siege of Szigetvár, however, successfully halted the Ottoman expansion towards the city of Vienna. The Ottoman victory was a Pyrrhic one. The death toll on the Turkish side counted above tens of thousands in just a month.

The Habsburg Monarchy ruler at the time was Maximilian II, Holy Roman Emperor. The Ottomans were ruled by Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent, who also led the invasion itself. Szigetvár’s defense was in the hands of Nikola Zrinski, a Croatian noble and a seasoned general. Zrinski had a flourishing military career and was also one of the most powerful landlords in the Croatian Kingdom.

The Little War

The beginning of the 16th century for Hungary was a time of near-constant conflict. The period from 1529 to 1552, known as the Little War, was marked by several major battles. During those battles, both the Ottoman Empire and the Habsburg dynasty suffered immense casualties.

Until the middle of the century, the territorial losses of Hungary were major. Nevertheless, this period of loss was reversed after the brilliant Hungarian victory at the Siege of Eger. After the defeat they suffered, the Ottomans renewed their conquest in 1566. During the years of war – and afterwards, in fact – Europe watched the movements of Suleiman’s army with apprehension. Yet when the time came, the Western rulers failed to take the right action.

Changing the course

![A miniature of Suleiman leading his men to Sziget. Source: [1]](https://www.warhistoryonline.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/64/2016/06/suleiman-at-sziget-432x640.png)

Reality in numbers

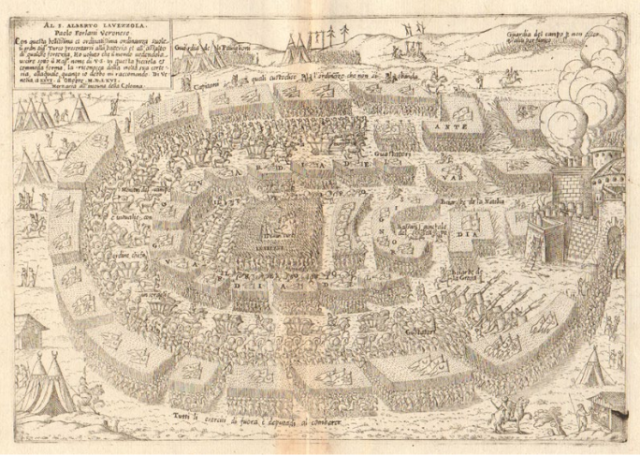

In the middle of summer, on the 2nd of August 1566, the Ottoman army reached their destination. Some historical sources put their numbers around 300,000, but this is still debated. A few years before that, he was fighting against the Safavid Empire, which must have drained his forces somewhat. Moreover, the Little War was also costly in lives and gold, and although the Ottomans had a considerable treasury, the logistics and necessary supplies for an army of that size would have been impractical at that point.

A more realistic number, according to some historians, would be 100,000, although even an army of this size would have caused some problems. The loss of many seasoned warriors in the previous decades of war meant that the current Ottoman army was smaller and less experienced than it had been in the past.

The Defense

Zrinski had to defend Szigetvár with around 2,300 men. Szigetvár’s defense was able to withstand the long siege due in part to the architecture of the stronghold, and their determination to last until reinforcements arrived. However, the imperial army bound to help Zrinski was at the time busy in another part of the Empire and Maximillian never issued an order for Zrinski to receive their aid.

The Siege and Battle of Szigetvár

The siege began on the 6th day of August.

During the siege, which lasted over a month, the defenders repulsed at least three all-out attacks. After weeks of relentless bombardment, the defenders were forced to retreat into the Old City. The struggle had taken the lives of the majority of the defenders already.

At this point, the Turks offered Zrinski a chance to surrender. If he had done so, they promised him a place as their vassal, ruling Croatia. Of course, he declined.

During the siege, on the September 6th, the Ottoman Sultan Suleiman passed away. However, news of his death was suppressed at first, on the orders of the Grand Vizier. It was thought that this event could lower the morale of the army, if word got out before the siege ended.

The following day was the last one for Szigetvár.

On September 7th, the Turkish force launched their final attack, bombarding the city with cannons and Greek fire, which spread like quickly and burned down much of the city. Szigetvár’s castle also fell victim to the flames.

Afterwards, the Ottoman forces poured into the city. Zrinski and his men prepared to face their enemy and an almost certain demise. The last of the defenders did not go down easily, killing hundreds of the attackers before they fell. They stood their ground Zrinski was killed, struck by Ottoman bullets and arrows.

A handful of his men were spared, as they had made a great impression with their bravery. Zinski’s body was decapitated, and his head brought as a gift to the new Sultan. Although the battle was over, Zrinski had one last minor victory. He had ordered a booby trap to be set in the castle, and when it was stormed by the Turks it exploded, taking the life of an estimated 3,000 Ottomans.

Aftermath

All of the Christian civilians were massacred by the Ottomans. The defenders were wiped out. However, the siege was a not favorable one for the Ottomans. Suleiman’s army, the most feared juggernaut, had lost a huge portion of their men. The numbers of attackers who fell during the 36-days siege could count anywhere between 20,000 to 35,000.

For Hungarians and Croatians, the fall of Szigetvár was a heroic defeat and is a memorable day in their history. To this day it remains an inspiration for literature and art.

On the other hand, for the Ottoman Empire, it marks the death of their renowned leader, Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent, and the loss of thousands of soldiers. Although the causes of their leader’s death are still debated, Szigetvár will remain the last campaign of the famous Sultan.

The fall of Szigetvár delayed the advancement of Ottoman forces for another century. For this reason, it is often referred to as “the battle that saved the civilization” – that exact quote comes from the infamous Cardinal Richelieu. Almost two years after the siege, the Treaty of Adrianople was signed, before significant territorial changes occurred. All of them were favourable to the Ottomans, but the peace was maintained until the Long War.

Bibliography:

- The Military History of Hungary : 1526–1697.From the Battle of Mohacs to the Battle of Zenta – Hondevelem.hu

- Turnbull, Stephen. The Ottoman Empire 1326–1699. New York: Osprey, 2003

- Wheatcroft, Andrew . The Enemy at the Gate: Habsburgs, Ottomans, and the Battle for Europe. Basic Books, 2009